11/18/2020

All, Purpose

The Duty Trap

We start off in life being very interested in pleasure and fun. In our earliest years, we do little but hunt out situations that will amuse us, pursuing our hedonistic goals with the help of puddles, crayons, balls, teddies, computers and bits and pieces we find in the kitchen drawers. As soon as anything gets frustrating or boring, we simply give up and go in search of new sources of enjoyment – and no one appears to mind very much.

Then, all of a sudden, at the age of five or six, we are introduced to a terrifying new reality: the Rule of Duty. This states that there are some things, indeed many things, that we must do, not because we like them or see the point of them, but because other people (very intimidating, authoritative people who may be almost three times our size) expect us to do them – in order, so the big people sternly explain, that we’ll be able to earn money, buy a house and go on holiday about 30 years from now. It sounds pretty important – sort of.

Even when we’re home and start crying and telling our parents that we just don’t want to do the essay about volcanoes for tomorrow, they may take the side of Duty. They may speak to us with anger and impatience – beneath which there is simply a lot of fear – about never surviving in the adult world if we develop into the sort of people who lack the will to complete even a simple homework assignment about lava and want to build a treehouse instead.

Questions of what we actually enjoy doing, what gives us pleasure, still occasionally matter in childhood, but only a bit. They become matters increasingly set aside from the day-to-day world of study, reserved for holidays and weekends. A basic distinction takes hold: pleasure is for hobbies; pain is for work.

It’s no wonder that by the time we finish university, this dichotomy is so entrenched, we usually can’t conceive of asking ourselves too vigorously what we might in our hearts want to do with our lives; what it might be fun to do with the years that remain. It’s not the way we’ve learned to think. The rule of duty has been the governing ideology for 80% of our time on Earth – and it’s become our second nature. We are convinced that a good job is meant to be substantially dull, irksome and annoying. Why else would someone pay us to do it?

The dutiful way of thinking has such high prestige because it sounds like a road to safety in a competitive and alarmingly expensive world. But the rule of duty is actually no guarantee of true security. Once we’ve finished our education, it emerges as a sheer liability masquerading as a virtue. Duty grows positively dangerous. The reasons are two-fold.

First, because success in the modern economy will generally only go to those who can bring extraordinary dedication and imagination to their labours – and this is only possible when one is, to a large extent, having fun (a state quite incompatible with being exhausted and grumpy most of the time). Only when we are intrinsically motivated are we capable of generating the very high levels of energy and brainpower necessary to shine out amid the competition. Work turned out merely out of duty quickly shows up as limp and lacking next to that done out of love.

The second thing that happens when our work is informed by our own sense of pleasure is that we become more insightful about the pleasures of others – that is, of the clients and customers a business relies upon. We can best please our audiences when we have mobilised our own feelings of enjoyment.

In other words, pleasure isn’t the opposite of work: it’s a key ingredient of successful work.

Yet we have to recognise that asking ourselves what we might really want to do – without any immediate or primary consideration for money or reputation – goes against our every, educationally embedded assumption about what could keep us safe, and is therefore rather scary. It takes immense insight and maturity to stick with the truth: that we will best serve others, and make our greatest contribution to society, when we bring the most imaginative and most authentically personal sides of our nature into our work. Duty can guarantee us a basic income, but only sincere, pleasure-led work can generate sizeable success.

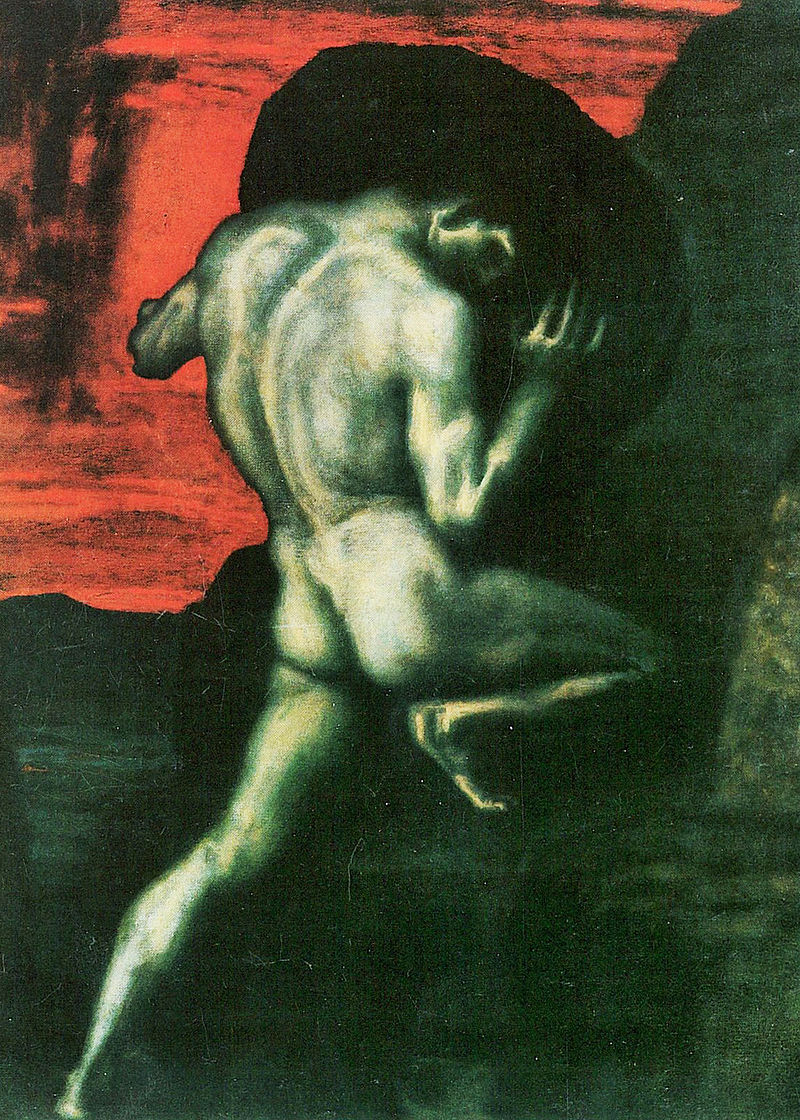

When people are suffering under the rule of duty, it can be helpful to take a morbid turn and ask them to imagine what they might think of their lives from the vantage point of their deathbeds. The thought of death may usefully detach us from prevailing fears of what others think. The prospect of the end reminds us of an imperative higher still than a duty to society: a duty to ourselves, to our talents, to our interests and our passions. The deathbed point of view can spur us to perceive the hidden recklessness and danger within the sensible dutiful path.