Sociability • Communication

On the Art of Conversation

Having a decent conversation is something most of us imagine we can do without any problem – and certainly without much thought. These things just happen naturally. Don’t they?

But in truth, truly good conversations come along very rarely; largely because our societies fall for the Romantic myth that knowing how to talk to other people is something we are born knowing how to do, rather than an art dependent on a little planning and a few skills. We rightly accept that total improvisation in preparing a meal is unlikely to yield good outcomes; but we show no such caution or modesty when it comes to how we might talk over the food once it has been made. Finding oneself in a good conversation can feel as haphazard and random as stumbling on a beautiful square in a foreign city at night – and realising one won’t reliably know how to get back there in daytime.

The search for better conversations should begin with the question of what a conversation is ideally for. And here two basic functions suggest themselves: confirmation and clarification.

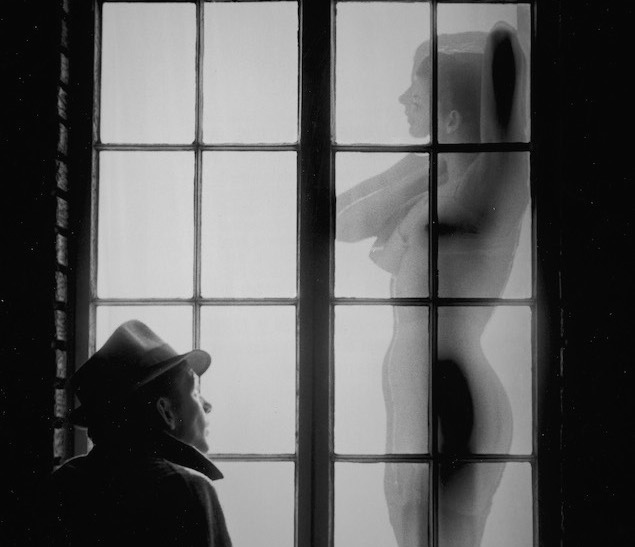

The official story of what life is like leaves out a daunting amount about who we really are. Too much of what we feel can’t normally be disclosed for fear that we’ll be humiliated or cause undue alarm or upset. Our envy of colleagues, our disappointments in love, our true feelings towards our families, our embarrassing habits and petty fears, our wilder political daydreams… little of this ‘silent normality’ has the chance to be discussed; until we find ourselves in a good conversation, by which is meant a conversation that – artfully, without prurience or judgement – manages to confirm the fundamental acceptability of hitherto carefully guarded emotions and ideas.

Shyness takes a lot of the blame for poor conversations. We get scared of opening our souls because we falsely exaggerate the difference between ourselves and others. We display only our strengths, vaunt only our successes, lay out only our conventional proposals – and bore others as a result because it is in the revelation of our weaknesses, in the display of our fragilities, in the confession of our wilder fantasies that we grow interesting and likeable. It is almost impossible to be bored when a person tells you sincerely what they have failed at or who has humiliated them, what they long for and when they have been at their craziest.

Then come the pleasures of clarification, conversations in which another person sharpens our ideas by correcting our tendencies to mental blankness and distraction. Thinking alone is hard, our minds jump away from the pressure to bring ideas into focus, preferring the charm of daydreaming or the internet instead. How helpful, therefore, to be able to embark on the job of thinking with someone who can hold us to the issues we need to refine, lend us courage to keep going with our hesitant opening thoughts and pollinate our analyses with their insights.

In too many countries, a misplaced fear of ‘pretension’ holds people back from raising the large rewarding topics – as though only very special people had the right to consider head on what it really means to be human. But is permission necessary to probe at the central assumptions of human life? When else are we meant to ask: What is the point of work? What makes a good relationship? How are we to raise children? What should we travel for? What should our nations be?

We should be braver and more demanding about the conversations we fall into. Rather than seeing successful examples as a gift, we should strive to become their regular engineers and cultivators.