Calm • Perspective

Perspectives on Insomnia

It’s far into the night, but sleep won’t come. You turn over. Perhaps a different position will quieten the mind. Or maybe the other side was better after all. Panic sets in. Not sleeping is a disaster.

For very understandable reasons our culture has arrived at extremely negative assessments of insomnia. It is a curse, to be overcome by art or science, by a sleeping pill, chamomile tea or sheep counting.

Being unable to sleep night after night, for weeks on end, is – of course – hell. But in smaller doses, insomnia does not need a cure. Occasional sleeplessness is an asset, a help with some key troubles of the soul. Crucial things we need may only get a chance to happen during a few active hours in the middle of the night. We should revise our assessment of sleeplessness.

Out of bed in the middle of the night … raising the prestige of not being able to sleep

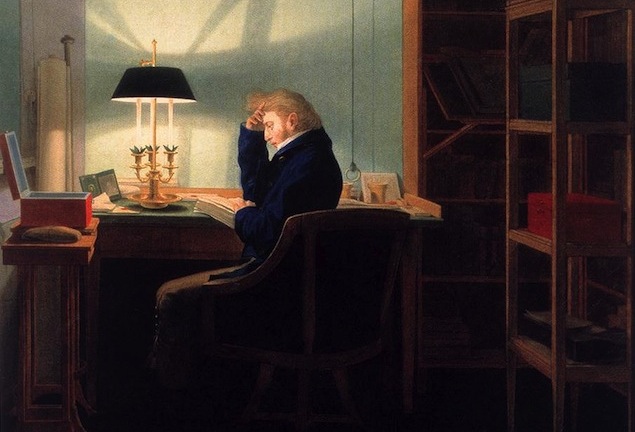

The Danish painter Kersting hints at the virtues of the sleepless state. We can guess it’s very late; more conventional people have long ago turned in, but the man has stayed up, to read, to think, to talk with a long-forgotten person: himself. Late at night is when big things may at last have a chance to happen in the mind. Like all the most interesting artists, Kersting is trying to make what really matters glamorous.

During the day, we are dutiful to others. At night we return to a bigger duty: to ourselves. Night is a corrective to the demands of the community. I may be a dentist or a maths teacher but, long before that happened and still now when I am allowed to commune with myself, I am simply a nameless, limitless consciousness, a far more expansive, un-anchored figure, of infinite possibilities and rare, disturbing, ambivalent, peculiar, visionary insights.

The thoughts of night would sound weird to my mother, my friend, my boss, my child. These people need us to be a certain way. They cannot tolerate all our possibilities and for some good reasons. We don’t want to let them down; they have a right to benefit from our predictability. But their expectations shape us, make us who we are, and choke off important aspects.

However, at night, with the window open and a clear sky above, it is just us and the universe – and for a time, we can take on a little of its boundlessness.

5 a.m. Free, until the first person she knows wakes up…

We don’t only suffer from spending insufficient time with our true deep selves. We also suffer because we are presented only with the daytime version of other people.

We need to have a lot more portraits of what people are like when they are alone, in the dim hours, and their heads are filled with odd (but so normal) thoughts. At two in the morning, the CEO thinks the company is futile – and yet she remains a good CEO. A mother thinks about walking out of her marriage and her family – and yet she will stay and no one need know. A successful novelist wishes he’d never started writing, feels everything he has done is pitiful. And yet he remains an insightful, consoling wordsmith. We need to know that people who are competent, capable and decent will also have (in the privacy of the night) thoughts which are deeply contrary to who we imagine them to be. Far from being disconcerting, this is properly consoling; a corrective to our debilitating sense of isolation and private madness.

It’s often been assumed that if you draw off the social pressure to be decent and responsible, monstrous parts of the self will emerge.

Goya: when we let go of our public identity we are revealed as monsters of selfishness and cruelty

Yet, social pressure is perhaps also keeping back sweet and delicate aspects of ourselves. We keep them under wraps during the day not because they are so awful, but because they are so liable to be misunderstood.

We can be rather strange and lonely – together

Late at night is when the bully recognises that he is cruel from anger and disappointment and that deep down, he is lonely and ashamed. A readiness to admit weakness, error and confusion, a readiness to be ashamed and to be sorry – these are not qualities encouraged by the bright, defensive brittleness of day. Only at night, without fear of consequence or humiliation, we start to regrow the more delicate aspects of our natures.

We are naturally very inclined to want to be normal. Yet thanks to insomnia, we are granted a crucial encounter with our weirder, truer selves. We can learn of our own apparent strangeness. The daytime self is a misleading picture of what everyone is like. Insomnia is a gift – and a latent education.

***

Insomnia may also provide the perfect occasion on which to think. It’s easy to forget how little strategic thinking ever gets done in the day. Judging by the ideas generated there, our beds have more of a right to be called our offices than our offices. Insomnia is the revenge of the many big thoughts one hasn’t had time to nurture in the daylight hours.

8.42am: not a good time for asking the big why questions

During the day, there are a thousand immediate issues to be sorted out. Our minds are dominated by what one could call lower-order questions: what’s the fastest way to get to the meeting in the city centre? How can I get the phone number of the restaurant to book a table for Thursday? What do I say to win the argument with my partner?

At the start of his ‘Ethics’, Aristotle points out that most of what we do is for the sake of something else. Someone makes a harness – to take his favourite example – so that a horse can be controlled. That means the cavalry can be more effective. So the general can win the battle. So the statesman can win the war. So the good society can be safe. Therefore, the lower-order activity, like making the harness, can ideally be understood as serving, at a distance, a higher-order concern – like maintaining a good society.

Philosophy, according to Aristotle, should be focused on the higher-order questions. It doesn’t focus on HOW to do things, so much as on WHY they might be worth doing.

In the rush of the day, there is no time for the higher-order questions: why do I waste my time with superficial social encounters? Why do I read the newspaper? Why was I so irrationally irritated with the person I profess to love?

At night, however, the ranking of first and second order questions is reversed. In the dark, one may investigate the meaning of work, the needs behind friendship, the mechanics of love. The topics are far from academic. We become philosophers when we chase the practical issues upstream.

The posture is misleading: we’re far more likely to get thinking when lying down in the dark

It’s very often ambitions that keep us awake. What am I really trying to do? What’s my life for? We sense and are tormented by our possibilities: how does one make more money, how can one be more effective, how can one make a difference…

These questions are terrifying because, at first, there tends to be no plan of action, simply an ambition waiting to be knocked down by the scepticism and mockery of others. To be turning over such issues and yet be a mere beginner feels like the ultimate arrogance. That is why one needs the protection of the night. Night offers us safety from the scepticism of sensible others. Like childhood, it allows us time to get ourselves together without needing to be always sure or impressive.

The architect Le Corbusier’s first sketch of an apartment building for a Parisian street, completed – like a lot of his work – late at night, in bed

In the middle of the night, you don’t have to make your case to a hostile audience. You can run with an idea that, to others, right now, would look feeble.

An early draft of Ulysses; James Joyce kept getting it wrong. But he kept going – almost always late at night

One of the most poignant things about artists is their endless capacity for sticking with quite bad, early versions of ideas. The finished, printed pages of James Joyce’s masterpiece Ulysses give no hint of the process by which they were produced. But the manuscript drafts do. We can see the crossed out sentences and paragraphs, the words that had to be shunted about, the passages that just didn’t work.

Being an artist always involves taking risks with serious imperfection; it means forgiving oneself for the horrors of the first, second and third drafts. In this particular sense, all of us should be artists: not of novels or buildings but of projects in our own lives. We need to keep faith with our goals without choking with disgust at our clumsy early manoeuvres.

What is true of art is true of life more generally. To successfully pull off a new business or an office reorganisation has much in common with the production of a novel or an apartment building. Lying in bed, as a delivery lorry trundles along a distant dual carriageway or a car door slams eerily somewhere along the street, we have to risk thinking through the first very, very imperfect version of a large plan.

The German writer and philosopher Friedrich Schiller believed in ‘withdrawing the watchers from the gate’. To be more creative, he suggested that we need to let our stranger, slightly crazy ideas get a hearing. We must not reject too soon. Later comes the business of selecting, ordering and polishing. But creativity involves being unusually willing to entertain the ridiculous and the fragmentary.

We want to arrive, eventually, at a feasible, defensible strategy. But we all have to start with thoughts that look extremely unimpressive and possibly absurd. Night is a friend to the slow process of maturation that every ambitious project demands: it provides us with the cover to grow into our more complete selves.