Leisure • Art/Architecture

Christo and Jeanne-Claude

Traditionally, artists made small, lovely things. They laboured to render a few square inches of canvas utterly perfect or to chisel a single bit of stone into its most expressive form.

Caspar David Friedrich in his studio; making a small bit of the world lovely

For several centuries, the most common size for art was between three and six feet across. And while artists were articulating their visions across such expanses, the large scale projects were given over wholesale to governments and private developers – who generally operated with much lower ambitions. Governments and the free market made big ugly things rather often.

We’re so familiar with this divergence that we tend not to think about it at all. We regard this polarisation as if it was an inevitable fact of nature, rather than what it really is – a cultural failing.

Christo was born Christo Vladimirov Yavachev in northern Bulgaria in 1935, on the same day that Jeanne-Claude was born in Casablanca.

It is because of this failing that the artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude (collectively known as Christo) stand out as quite so important. Christo points the way to a new kind of art and a new kind of public life. Christo have been the artists most ambitious about challenging the idea that artists should work on a tiny easel – and keenest to produce work on a vast industrial scale.

Other artists have experimented more widely and addressed us more intimately. What’s distinctive and important about Christo is that they want to make art that can fill the sort of expanses previously associated with airports, motorways, supermarkets, light industry zones, marshalling yards, factories and technology parks.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude started exploring the effect of having an impact on quite big things, around 1968, when they draped a medieval Italian tower.

Wrapped Medieval Tower, Spoleto, Italy, 1968

The idea was pushed much further when they wrapped a whole bit of coastline in Australia.

Next they slung an enormous orange curtain across a valley in Colorado.

Then they got around to surrounding some islands off the coast of Florida with 6.5 million square feet (603,870 square meters) of floating pink woven polypropylene fabric.

Surrounded Islands, Biscayne Bay, Greater Miami, Florida, 1983

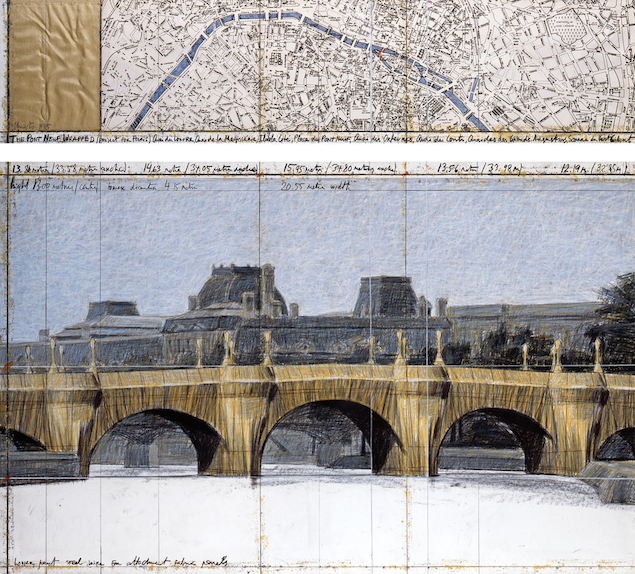

They then wrapped the Pont Neuf in Paris.

And in 1991, in a simultaneously project, installed thousands of umbrellas for forty miles along two valleys, one in the US and one in Japan.

The Umbrellas, Japan-USA, 1991

Wrapped Reichstag, 1995

And in 1995, they carried out a monumental project in Berlin. They veiled the German Reichstag, which was the traditional seat of national authority and also the focus on intensely painful memories because of its association with the rise of the Nazi party. And then they spectacularly unwrapped it in an act of national renewal.

Christo has gone far beyond even traditional architecture, the standard next step up from art: they occupy a space normally occupied by city planners or civil engineers constructing a container port or landscape architects laying out parkland around a town.

Christo can look very innovative, but in a way their conception of art is deeply traditional. What they mean by art is making beautiful things. They might be wrapping things or surrounding them, or marking routes with flags and banners, but what guides them is the search to make the world more beautiful. Only not just a little bit at a time. The scale of their efforts to make the world beautiful has been stupendous – and inspiring.

Curtain Valley, 1972

Curtain Valley, catching the sunlight, was visible for miles. Millions of people wandered through the enchantingly remade Central Park.

The Gates, Central Park, New York City, 2005

Perhaps the biggest thing Christo has done, however, is to indicate a direction of travel, which doesn’t stop with the great things they themselves happen to have done.

One key move is not to stop with imagining something wonderful but to work out how to make the imagined thing come real. Rather than picture a revitalised central Park, they revitalised it. Rather than imagine Germany renewing its feelings about its historic centre of government, they made it happen. The ideal task of the artist isn’t just to dream of a better world, or complain about current failures (though both are honourable); rather it is to actually make the world finer and more elegant.

One Million Square Feet, Little Bay, Sydney, Australia 1969

The primary identity of Christo is an artist. But to operate realistically on a large scale, they needed to deploy many of the skills traditionally associated with business and which we think of as the domain of the entrepreneur.

Heavy engineering: the Japanese umbrella project

Christo had to negotiate with city councils and governments; they had to draw up business plans, arrange large scale finance, employ the talents and time of hundreds even thousands of people, coordinate vast efforts and deal with millions of users or visitors. And all the while, they held on to the high ambitions associated with being an artist.

Furthermore, crucially, Christo worked out how make a profit while doing all this. Profit wasn’t the primary goal. But profitability meant it was possible to go onto the next project (they have never received private or public subsidy). Christo has made a fortune out of what they have been doing.

The way they made money was fascinating: they financed a project by selling the plans and drawings for it. It was like Plato financing a new state by selling copies of the Republic (except, unlike Plato, Christo made their utopia happen).

The plan financed the real work

Christo is a key exemplar of the crucial proposition that the creation of beauty isn’t a commercial luxury, but potentially a central plank of good commerce. They hint at a tremendous ideal: if making something beautiful could become a major way of increasing shareholder value, then the immense forces of investment could start to line up in the right direction.

Christo is showing us that ideally artists should absorb the best qualities of business. Rather than seeing such qualities as opposed to what they stand for artists, following Christo’s lead, should see these as great enabling capacities, which help them fulfil their beautifying mission to the world. In the future, an artist might spend as much time being trained by the Wharton School of Business or INSEAD as by the Royal College of Art.

Christo has never got to build an airport or a supermarket or lay out a new city – but the ideal next version of them will.