Leisure • Literature

Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf was a writer concerned above all with capturing in words the excitement, pain, beauty and horror of what she termed the Modern Age. Born in 1882, she was conscious of herself as a distinctively Modernist writer, at odds with a raft of the staid and complacent assumptions of 19th-century literature.

She realised that a new era – marked by extraordinary developments in urbanism, technology, warfare, consumerism and family life – would need to be captured by a different sort of writer. Along with Joyce and Proust, she was relentlessly creative in her search for new literary forms that would do justice to the complexities of modern consciousness. Her books and essays retain a power to convey the thrill and drama of the 20th century.

Woolf’s father, Sir Leslie Stephen

Virginia Woolf was born in London: her father was a famous author and mountaineer, and her mother a well-known model. Her family hosted many of the most influential and important members of Victorian literary society. Woolf was largely cynical about these grand types, accusing them of pomposity and narrow-mindedness. Woolf and her sister weren’t allowed to go to Cambridge like their brothers, but had to steal an education in their father’s study.

Woolf as a child playing cricket with her sister

After her mother died when she was 13, Woolf had the first of a series of mental breakdowns that were to plague her for the rest of her life – partly caused by the sexual abuse she suffered at the hands of her half-brother George Duckworth.

Despite her illness, she became a journalist and then a novelist – and a central figure in the Bloomsbury group, which included John Maynard Keynes, E.M. Forster, and Lytton Strachey. She married one of the members, the writer and journalist Leonard Woolf.

The two Woolfs

She and Leonard bought a small hand-printing press, named it The Hogarth Press, and published books from their dining room. They printed Woolf’s radical novels and political essays when no one else would; and produced the first full English edition of Freud’s works.

In just four short years between World Wars I and II, Woolf wrote four of her most famous works:

Mrs Dalloway (1925)

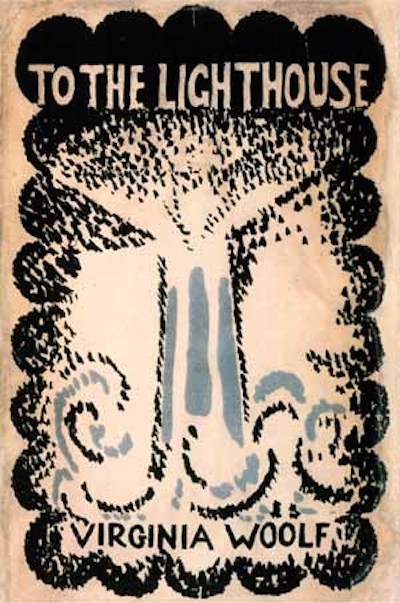

To the Lighthouse (1927)

Orlando (1928)

and the essay

A Room of One’s Own (1929)

In March 1941, feeling the onset of another bout of mental illness, she drowned herself in the river Ouse.

Her work has many vital things to teach us.

1. Notice Everything

Woolf is one of the great observers of English literature. Perhaps the finest short piece of prose she ever wrote was the essay, “The Death of the Moth,” published in 1942. It contains her observations as she sits in her study watching a humble moth trapped by a pane of glass. Rarely have so many profound thoughts been eked out from such an apparently minor situation (though for Woolf, there were no such things as minor situations):

“One could not help watching him. One was, indeed, conscious of a queer feeling of pity for him. The possibilities of pleasure seemed that morning so enormous and so various that to have only a moth’s part in life, and a day moth’s at that, appeared a hard fate, and his zest in enjoying his meagre opportunities to the full, pathetic. He flew vigorously to one corner of his compartment, and, after waiting there a second, flew across to the other. What remained for him but to fly to a third corner and then to a fourth? That was all he could do, in spite of the width of the sky, the far-off smoke of houses, and the romantic voice, now and then, of a steamer out at sea.”

Woolf at Monk’s House

Woolf noticed everything that you and I tend to walk past: the sky, the pain in others’ eyes, the games of children, the stoicism of wives, the pleasures of department stores, the interest of harbours and docks… Emerson (one of her favourite writers) may have been speaking generally, but he captured everything that makes Woolf special when he remarked: “In the work of a writer of genius, we rediscover our own neglected thoughts.”

In another great essay, “On Being Ill,” Woolf lamented how seldom writers stoop to describe illness, an oversight that seemed characteristic of a snobbery against the everyday in literature:

“English, which can express the thoughts of Hamlet and the tragedy of Lear, has no words for the shiver and the headache. The merest schoolgirl, when she falls in love, has Shakespeare or Keats to speak her mind for her; but let a sufferer try to describe a pain in his head to a doctor and language at once runs dry.”

This would be her mission: Woolf tried throughout her life to make sure language would do a better job at defining who we really are, with all our vulnerabilities, confusions and bodily sensations.

Woolf raised her sensitivity to the highest art form. She had the confidence and seriousness to use what happened to her – the sensory details of her own life – as the basis for the largest ideas.

2. Accept the Everyday

Woolf was always profound, but never afraid of what others called trivial. She was confident that the ambitions of her mind – to love beauty and engage with big ideas – were completely compatible with an interest in shopping, cakes and hats, subjects on which she wrote with almost unique eloquence and depth.

In another particularly good essay of hers, called “Oxford Street Tide,” she celebrates the gaudy vulgarity of this huge London shopping street.

“The moralists point the finger of scorn at Oxford street… it reflects, they say, the levity, the ostentation, the haste and the irresponsibility of our age. Yet perhaps they are as much out in their scorn as we should be if we asked of the lily that it should be cast in bronze, or of the daisy that it should have petals of imperishable enamel. The charm of modern London is that it is not built to last; it is built to pass.”

Oxford Street in the 1930s

In an accompanying essay, equally open to the unprestigious side of modern life, Woolf goes to visit the giant docks of London:

“A thousand ships with thousand cargoes are being unladen every week. And not only is each package of this vast and varied merchandise picked up and set down accurately, but each is weighed and opened, sampled and recorded, and again stitched up and laid in its place, without haste, or waste, or hurry, or confusion by a very few men in shirt-sleeves, who, working with the utmost organisation in the common interest… are yet able to pause in their work and say to the casual visitor, “Would you like to see what sort of thing we sometimes find in sacks of cinnamon? Look at this snake!”.

3. Be a Feminist

Woolf was deeply aware that men and women fit themselves into rigid gender roles, and as they do so, overlook their fuller personalities. In her eyes, in order to grow, we need to do some gender-bending; we need to seek experiences that blur what it means to be “a real man” or “a real woman.”

Woolf had a few lesbian affairs in her life, and she wrote a magnificently bold queer text, Orlando, a portrait of her lover Vita, described as a nobleman who becomes a woman.

Vita Sackville-West in her twenties

“It is fatal to be a man or woman pure and simple; one must be woman-manly or man-womanly.” (A Room of One’s Own).

In her anti-war tract, Three Guineas, Woolf argued that we will only ever end war by rethinking the habit of “pitting of sex against sex… all this claiming of superiority and imputing of inferiority… belong to the private-school stage of human existence where there are ‘sides,’ and it is necessary for one side to beat another side, and of the utmost importance to walk up to a platform and receive from the hands of the Headmaster a highly ornamental pot.”

Woolf wished desperately to raise the status of women in her society. She recognised that the problem was largely down to money. Women didn’t have freedom, especially freedom of the spirit, because they didn’t control their own income: ‘Women have always been poor, not for two hundred years merely, but from the beginning of time. Women have had less intellectual freedom than the sons of Athenian slaves. Women have not had a dog’s chance of writing poetry.’

Her great feminist rallying cry, A Room of One’s Own, culminated in a specific, political demand: in order to stand on the same intellectual footing as men, women needed not only dignity, but also equal rights to education, an income of “five hundred pounds a year” and “a room of one’s own.”

****

Woolf was probably the best writer in the English language for describing our minds without the jargon of clinical psychology. The generation before her, the Victorians, wrote novels focused on external details: city scenes, marriages, wills… Woolf envisioned a new form of expression that would focus instead on how it feels inside to know ourselves and other people.

The Dreadnought hoaxers in Abyssinian regalia; Woolf is the bearded figure on the far left

Books like Woolf’s—which aren’t overly sarcastic, caught up in adventure plots, or cradled in convention—are a contract. She’s expecting us to turn down the outside volume, to try on her perspective and to spend energy with subtle sentences. And in turn, she offers us the opportunity to notice the tremors we normally miss, and to better appreciate moths, our own headaches and our fascinating and fluid sexualities.