Leisure • Sociology

St. Benedict

The fiercely individualistic spirit of our age tends to take a dim view of two big ideas: having any sort of rules governing everyday life; and pooling resources to live together in a communal way.

We’ve come to see ourselves as, each one of us, needing to invent our own unique way of life, governed by our instincts and what we most feel like doing in the moment. As for the idea of community, though it might cross our minds every now and then (especially when we contrast how fun it was at college and how rather arduous and lonely it might be now), nothing in modern capitalism enables us to imagine how we’d ever manage to make the group, rather than the ‘I’, the centre of things. Everything from domestic appliances to mortgages to romantic love enforces the idea of the lone or couple-based unit. We’re influenced by an ideology of personal freedom, where pursuing private ends is seen as the only path to happiness – though the results do not necessarily match the hopes. The joys of being part of a gang are simply not on the radar.

These attitudes, which we take for granted today, contrast so strongly with an idea which flourished for very long periods in many parts of the world and continue to have much to teach us about our real longings: monasticism. Monasticism puts forward the bold thesis that people can actually lead the most fruitful, productive and happy lives when they get together into controlled, organised groups of friends, have some clear rules and direct themselves towards a few big ambitions. Even if you’re not planning on setting up a secular version of a monastery any time soon (though we believe – as you’ll see – that this would be no bad idea), monasticism deserves to be studied for the lessons it yields about the limits to modern individualism.

One of the earliest and most influential figures in the history monasticism – in its Christian, Western guise – was a Roman nobleman living at the end of the 5th century, by the name of Benedict. In his twenties, Benedict studied Philosophy in Rome. For a time, he shared the dissipation, wastefulness and lack of genuine ambition of his wealthy fellow students until he suddenly became weary and ashamed and went off to the mountains in search of a better way of living. Other people soon joined him and he naturally found his way to starting a few small communities. From there, it was a natural step to write an instruction manual for his followers, with a simple and emphatic title: The Rule.

Within his lifetime, hundreds of people signed up to live in communities governed by his principles. And for over a thousand years, hugely impressive institutions founded in his name played a central role in European civilisation.

Benedict was an intensely devoted Christian. But it’s not necessary to share his beliefs in order to recognise that his recommendations tapped into something fundamental about human nature. His insights into communities are – in fact – detachable from the particular religious environment in which they were originally developed.

One: The Pleasures of Rules

The rules for living drawn up by Benedict were beautifully precise and detailed. His starting point is a pessimistic view of human nature. He’s acutely aware of how readily our lives go off the rails in big and little ways when we just do whatever comes to mind.

His rules include instructions on:

Eating

Rule 39: Except the sick who are very weak, let all abstain entirely from eating the flesh of four-footed animals.

Benedict was very concerned about eating the sort of foods that make you sluggish, self-pitying and slow. He recommended that one should consume modest but nutritious meals only twice a day. (An occasional glass of wine was allowed.) Lamb and beef were to be avoided, but chicken and fish in small quantities were ideal. Benedict was wise enough to see that being an intellectual was entirely compatible with thinking a lot about what one should eat – and his search was for the sort of food that would best nourish and nurture our minds. He thought that everyone should sit together at long tables, but he was also aware of how much idle banter there can be at meals, so he advised that diners should generally listen to someone reading from an important and interesting book while they made their way through lemon chicken with courgettes and beans. If they needed something, they should make a signal with their hands.

Silence

Benedict knew the benefits of silence. When you’ve got a big task on, concentration is key. He knew all about distraction: how easy it is to want to keep checking up on the latest developments, how addictive the gossip of the city can be… That’s why his communities tended to be set up in remote locations, often close to mountains, and his buildings featured heavy walls, quiet courtyards and beautifully serene living quarters.

Benedictine Arch Abbey of Pannonhalma, Hungary. Contemplation room.

Hair and Clothing

Fashion was, in Benedict’s time, as in ours, a huge source of interest, expense and attention. Benedict was himself a handsome man, but he was keen to put a limit on how much he or anyone else would think about what they had to wear every day. That’s why he recommended that everyone in his community wear the same clothes: plain and useful, not too expensive and easy to wash. What’s more, everyone should have their hair cut the same way – very, very short.

Balance

Rule 35: Let the brethren serve one another, and let no one be excused from the kitchen service except by reason of sickness

If you are going to be concentrating quite a lot on ideas and intellectual activities, Benedict knew it could be really helpful also to do some physical activity everyday; something repetitive and soothing might be ideal, like sweeping the floor or weeding a row of lettuces. You might also occasionally take your turn preparing a meal or doing the washing up – everyone does. But mostly it will be other people’s turns so you’ll be free – and guilt free.

Early Nights

You have to go to bed early and get up very early, Benedict knew that. Routine is crucial. You don’t suddenly want to be engaging in a conversation that starts at 11pm, gets rather heated around midnight and leaves you tossing and unable to sleep at 1pm. Get used to winding down systematically, focusing your thoughts and arranging your mind for the next day (a lot of good thinking happens when we’re asleep).

Monk’s bedroom, designed by John Pawson, Monastery of Novy Dvur, Czech Republic.

No porn addiction

Benedict knew that sex gets in the way. But it’s no use thinking endlessly, in repetitive cycles, about naked people when you’ve got really key things to get on with. He wasn’t a prude, and had a great deal of fun as a student, but he knew how short life was and how much he had to do. That’s why he recommended that in the ideal community, everyone should dress in a fairly demure way and that there should be no encouragement given to sexual feelings. Sex simply plays havoc with any attempts to concentrate.

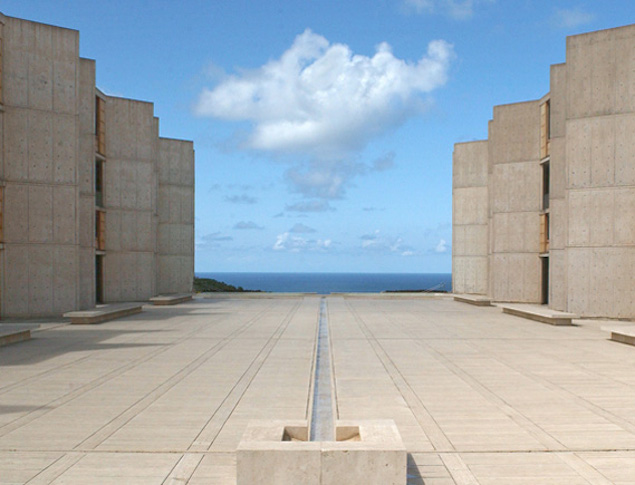

Art/Architecture

At many strategic points in Benedict’s buildings, you’ll see beautiful or dramatic works of art that remind you of some important idea or help you get into a useful mood. Benedict didn’t think that good art and architecture were luxuries: these were vital supports for our inner lives. He understood that we were likely to take our cue about how to be inside ourselves by looking around at the moods emanating from the walls around us. That’s why Benedictine monasteries have long employed the best architects and artists, from Palladio and Veronese to John Pawson in our own times. If you’re going to live together, it makes sense to create a home that is as uplifting and as calming as can be.

Wedding Feast at Cana, Veronese, Monastery of San Giorgio, Venice

Archabbey of Pannonhalma, Hungary, John Pawson

The point isn’t so much that we should particularly embrace the specific rules drawn up by Benedict; rather he is showing us something more general: the potential for rules to help us live well.

There are periods in life (and history) when it seems as if gaining freedom is the key to a great time. To a four-year-old, who has always been told when to get up, when bath time is and when the lights go out, it’s natural to suppose that it’s wonderful to be old enough to decide for oneself. But rules about how to live – and the authority to get us to stick with them – start to look more important, even wise, when we have a more urgent sense of the problems to which wise rules are possible solutions, when we realise how prone we are to distraction, dissipation, weakness of will and late-night squabbles. At that point, we may learn that rules – far from being interruptions of our native good selves – are really the restraints that safe-guard our best possibilities. They make us truer to who we want to be than a system which allows to do anything whatsoever.

Two: The Highlights of Community

Benedict established his first monastery at Monte Cassino – about halfway between Rome and Naples. It’s still there (although it had to be rebuilt after it was damaged by allied bombing in 1944).

The lofty – and rather inaccessible – location wasn’t an accident. The point of going to a monastery was to avoid the distractions that might take one’s attention away from what’s really important. We might not share Benedict’s idea of what’s important, but we deeply share the underlying concern: how to focus effectively on what we really want to accomplish and not get distracted all the time.

Benedict acknowledges that it’s hard for creatures like us to ponder the nature of God, examine our own failings or decode the meaning of some obscure Biblical passage – when our natural instincts draw us to eating too much, having sex, scratching our bottoms, getting drunk and gossiping.

Under Benedict’s inspiration, monasteries made a range of dazzling innovations in the field of non-distraction studies. Benedict proposed that to avoid distraction, one might need to live far removed from towns and cities. The architecture should be rather grand and imposing – as a continual reminder of the importance of what one is doing. One should live on-site and not commute in. The walls are going to have to be high and thick. There can’t be lots of doors or big picture windows looking out onto the wider world. Walls, cloisters and being a good few miles from the local tavernas certainly help in the fight against distraction.

Library, Benedictine Abbey of Admont, Austria

The ideal of the monastic community is that living collectively enables people to accomplish more than would be possible by individual effort.

Some aspects of how Benedict imagined that going – like the segregation of the sexes – don’t seem so compelling. But we still need some of the advantages of communal living.

It’s something we can see in action in the housing market. The Royal Crescent in Bath, for instance, is an example of collaboration around accommodation and architecture. Today, around two hundred people live in this building, mostly in modestly sized flats. If, for roughly the same money, they each had a small house it would look something like this:

However, by pooling the fabric of their homes, they collectively share one of the world’s greatest urban structures. Individually, they all have to deal with phone plans, wifi systems, electricity bills, council taxes, plumbing emergencies. But quite possibly one administrator could do it all for them – with an immense saving in terms of frustration. We’d all gain so much by giving up a little of our famed, but actually rather exhausting, individualism.

Monasteries frequently evolved into successful business centres, operating the major industries of the day: farming and mining, schools, hospitals and the early versions of hotels.

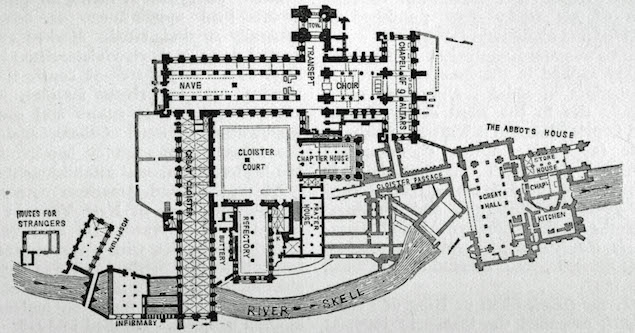

Layout of a Benedictine monastery showing factory, offices, workers’ accommodation, boardroom, restaurant. The hotel is on the lower left.

We think we understand collaboration in business. But actually, we are generally only looking at quite a limited range of options. We still assume that in a medium sized company, 157 people will all need to travel in by slightly different routes, all park their cars and in the evenings, all spend their money individually on chicken noodles, rent, a sofa bed and going to a bar.

Many big undertakings of the modern world could be pursued so much more effectively from within a monastery: a great graphic design company, a biotech corporation, a television production firm.

Conclusion:

Communal life can be much more enjoyable and less stressful than the nuclear family, with all its disappointments and pressures. We keep imagining that happiness lies in finding one other very special person (then rail against them for not being perfect enough) or else that it must be about becoming something extraordinary ourselves – rather than joining lots of other very ordinary people to make something superlative. We’d generally be so much better off joining a team. We’d be able to do things on a grander scale and get them done more easily – and more often have our minds in proper focus. That’s why Benedict remains a provocative and useful thinker.