Work • Business Skills

Towards Better Collaboration

Although collaboration – the extraordinary business of having to work with other people – is one of the major facts of modern life, it remains strangely unstudied and undiscussed as a formal topic. Our culture does not typically invite us to pay close and admiring attention to successful collaborative efforts, nor to immerse ourselves in learning the lessons from painful, failed joint ventures.

We are – without being much aware of it – guided by a strong Romantic prejudice in favour of lone creators. This is where we focus our attention and derive our models of work from. The largest stories we tell ourselves about creating things concern artists, isolated actors who operate without relying on anyone other than themselves.

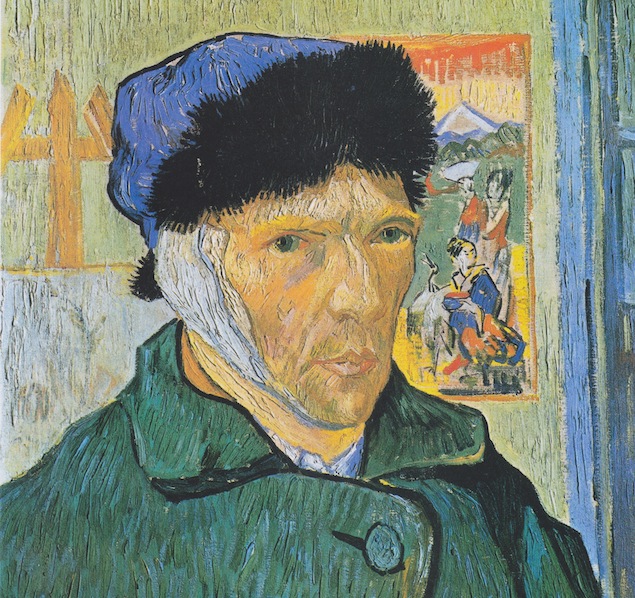

Vincent Van Gogh, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear (1889)

One person painted this canvas yet and there are – at this moment – 4,876 books about the man.

We’re much less familiar, and much less culturally appreciative, of the kind of labours that went into creating things like the Jean-Luc Lagardère assembly plant at Toulouse-Blagnac in south-western France, where the Airbus 380 is put together.

8,000 people were involved in making the hangar and assembly line, but we generally don’t know anything at all about their lives or labours. We don’t have burned into our imaginations stirring tales of the key meetings at which a group of senior executives took the major decision to focus final production in Toulouse rather than Hamburg or Filton; nor of the late night meetings at which specialists in wing design got together with the people who were in charge of the landing gear to make sure that their scheduling needs would be catered for within the new facility.

And yet this neglect of collaboration is no inconsequential matter. Some failures around collaboration are due to procedural and practical problems. For example: meetings are scheduled at inconvenient times, the layout of a room doesn’t facilitate interaction, the management architecture of a corporation means that people in different departments find it really hard to understand one another; the email system doesn’t allow for group discussions…

At The School of Life [the parent company of The Book of Life], our focus is slightly different. We’re interested in the psychological problems that get in the way of good collaboration. Our goal is to understand how organisations trip up even when the technology is in place, the architecture is pleasing and the staff have all the right qualifications on paper – because everyone is bringing what might be called ‘problems of character’ into the office with them.

The root cause of a lot of difficulties in collaboration is nothing less than emotional. Emotional issues are not an incidental aspect of modern business; they are not a vague phenomenon that one might chose to worry about only when all other issues have been solved. No ambitious business can afford to ignore the momentous goal of improving levels of emotional maturity.

It’s an agreed part of joining any modern office that we quite quickly get to know the quirks of people around us. Because many of these quirks are weird and distressing, we often feel an urge to chat about them with others, perhaps in the coffee shop around the corner from the office. This activity is sometimes dismissed as mere ‘gossip,’ but something important is going on when we air views on, for example, the manner of the guy in sales or the notorious temper of the IT chief. We are chatting because we are frightened and upset and want to air our puzzlement at how others behave. We gossip in order to release tension – and because collaboration is so hard.

Office gossip tends to feel extremely individual (it’s all about Megan or Dave or Ida), but if one takes a step back, all the endless permutations of complaint we have about people tend to boil down to some core flaws that keep recurring in people. There are, in our eyes, ten problematic character traits in people that make office life so hard.

Ten Anti-Collaboration Traits

One: Defensiveness

Defensiveness is an a priori need to reject criticism. It raises the cost of disagreement hugely, for whenever a defensive person meets with anything, however small, which is negative about themselves and their behaviour, their response is both very large and extremely severe. This is because, inside themselves, they take the attack to be entirely personal and therefore catastrophic. There is in their minds no distinction between a criticism of their work – and a criticism of their very being and right to exist.

It becomes deeply depressing to have any sort of tricky discussion with them about anything. It’s guaranteed to flare up. One wants to point out that something is a little late; but is there really a point when a drama is going to ensue? Organisations can put up with defensive people for a long time, but the relationship tends to get more and more joyless – and eventually, no one is too sad when a decision is taken to part ways.

Two: Irrational Rivalry

Rivalry can be very beneficial: for example, when you have two sales teams seeking the best quarterly results; two research groups pursuing different strategies to solve a major problem; or many analysts competing to provide the most accurate and most useful overview of an issue.

But there are individuals who bring rivalry into areas that don’t require it – and certainly don’t benefit from it. For example, a busy executive is assigned a smart young assistant to take some of the less complex issues off their desk. But instead of making the best use of this help and streamlining their own efforts, the executive starts to worry that their assistant is doing too well; they think (incorrectly) that if the assistant is a success, their own job will soon disappear. So they start to make life difficult for them. They get reluctant to pass on tasks and they get extremely agitated the day their assistant is praised by the CEO. They would rather some of their work was done badly, or not at all, than that their helper should do it well.

It feels as if there is only space for one of them to thrive and they are in competition for the limited affection of a superior. This is the definition of irrational rivalry: rivalry with no sane productive business end.

Three: People-Pleasing

People-pleasing means a manic terror of passing on information, however important, that might upset others. It is deeply problematic, for it confuses being polite with withholding information. It blurs the line between lying and pleasing.

Successful nations and businesses are never sentimental around bad news: they are founded on the principle of the free flow of the most awkward bits of information.

Four: Negativity

The negative person knows things are going to go wrong. They’ve been there before – and can’t resist pointing out drawbacks and dangers. In their mind, being negative is the way to be wise: it means seeing through the foolish delusions and naive hopes of others. Collaborating with them is hard: they kill ideas very early.

Negativity belongs to a mindset that might rudely be called inner feudalism.

14th-century rural scene of reeve directing serfs, from the Queen Mary Psalter

In some part of their brains, the guys doing the threshing know that big decisions are taken all the time, castles get built, people rise to power and courage make fortunes. But in their own lives, none of these feats seem remotely possible. They have been inculcated with the view that no improvements are likely, everything will stay the same and if you try to improve things you’ll get into trouble and it will all go wrong anyway.

Outwardly the age of feudalism is long, long gone. But inwardly, some of its characteristics remain even in a time of democracy, freedom and laptop computers.

Five: Bluster

At first they can seem rather exciting to work with. They like throwing out big ideas, and are great at sketching exciting scenarios about how everything might work out. But there’s a snag. Their optimism is excessive – and compulsive. They refuse to consider the downsides seriously, even when something is inherently rocky. They regard anxiety about possible bad outcomes as a sign of weakness. They won’t take risks seriously.

They are very difficult to collaborate with because they tend to be impatient with detail, which they regard as unimportant. They see concern with specifics as ‘fussy’, hardly worth bothering about. It’s as if, at some point, they had been over-exposed to a very unhelpful picture of what it means to focus on details. They suffered at the hands of someone a bit too plodding and unimpressive, someone genuinely pedantic and nit picking. And now lots of things that are actually very important are seen by them as mere ‘fussing…’. They are perhaps in flight from an over-protective, over-cautious mother.

Charles Dickens’ character Mr. Micawber (from the novel David Copperfield) is full of bluster and ill-grounded optimism.

He always believes that ‘something will turn up’ and has a remarkable ability to fail to learn anything from his past troubles. The difficulty is that moment by moment he appears confident and reasonable. He talks well (in general terms) about the opportunities and all the projects he has on the go. It can take some time before one realises that this person’s confidence is not in fact well-grounded – and is in fact highly dangerous to the whole team.

Six: Over-Control

The control-freak has a horror of letting other people do things. No matter how pressed for time or overburdened they might be, they are very reluctant to let any decisions or tasks leave their desk. Sharing and delegating causes them real anxiety.

Control is often a virtue. It means taking responsibility for getting something right; it’s the conviction that certain tasks are worth a lot of personal effort. But in patterns of over-control, other people are always seen as obstacles to doing things well. They are just a bunch of idiots, somehow in the way of getting to a good result.

Seven: Secret Manoeuvring

Secret manoeuvring is a pattern of behaviour whereby one quickly gives up on the people one is meant to be collaborating with, fails to talk to them about one’s disappointments – and instead works around them with the help of a few select not-always-officially-sanctioned colleagues.

A secret manoeuvrer may seem supportive; and may appear to have taken a suggestion quite positively. In the meeting, they didn’t raise any objection. They gave you a big smile. They sent you a message saying they thought your idea was very interesting.

What you don’t realise yet is that behind the scenes, they have a very different attitude. This is a person who is determined to get their way. But they don’t want to risk stating their intentions openly. They very much dislike confrontations and show downs. Even acknowledging disagreement can be quite upsetting to them. However, they are not at all passive or willing just to put up with things they don’t like.

They just hate conflict a lot and despair of others very fast. They worry that if they have to convince everyone, nothing will get achieved. They are pessimistic about communication. So they go intently to work – only you won’t see what they are up to. They hate the idea of keeping people informed. They set up secret side groups. It’s meant to be a collaboration between 20 equals. But they go out and hire two external consultants who they set up alongside the 20 that are meant to be doing the job. Secret manoeuvrers are constantly quickly losing faith with the people they’re meant to be working with, and briefing against their intended collaborators behind their backs.

It all sounds dark and Machiavellian – but it’s important to realise where the secret manoeuvring is coming from. It’s the outcome of a deeply ambitious personality that has very low faith in others and in their own ability to work through a problem with someone. In their personal life, the secret manoeuvrer may well have a lover and a spouse: they’re disappointed with the partner they married, but they haven’t come around to expressing what they really feel. It seemed better to steer around the conflict and start up a new relationship on the side.

They’re doing in business a version of what they’re doing in their marriage. They’re devoting themselves to ‘lovers’ because they can’t tolerate the tensions and ambiguities of sticking with the group they’ve originally pledged themselves to.

Eight: Unfriendliness

There are people at work who don’t do ‘nice’. They quickly let you know that they don’t waste their time on (as they see it) the minor niceties of massaging people’s egoes, giving out the occasional words of encouragement, smiling or asking about how the holidays went.

They are markedly abrupt. They tell you straight out they didn’t much like your ideas. They thought your section of the report was poorly presented – and weakly argued. They never seem to sugar-coat bad news. They won’t soften the blow. They are almost impossible to impress. And their demeanour suggests they really don’t think your approval is worth having in the first place. They tend to regard more gentle behaviour as a mere disguise for inefficiency. They bring the mood down. They don’t stoke enthusiasm. They are cynical about rousing speeches. They feel they have to be mean to win.

Nine: Slyness

At the end of the table, looking perhaps rather dapper or elegantly turned out, there’s one member of the team who seems not quite to regard things as serious. They can be very charming and good company (for a while). But they give the impression they are just ‘holidaying’ at the company; or that they are working for ‘fun’ rather than because they really have to. In some way their reasons for being here are not like those of others. Some large part of their life, which they hint at but don’t fully describe, is more important than what is going on in the room. Maybe they are about to inherit a fortune, maybe in their bedroom they designed an app which is about to go global, maybe a relative owns the whole corporation and they’re working incognito to get a feel for the various departments before taking over.

They are quietly superior. They don’t seem to care a great deal how things turn out. Their contributions make people laugh, or lighten the mood – but they don’t really seem to grapple with the issues. And somehow they never seem to end up doing the more grinding tasks. They often have to head off to a lunch; their use of the expense account is technically right but somehow wrong in spirit.

At an industry reception, you notice them chatting in a very chummy way to a senior person in a rival firm. You’d not be surprised if they were saying some rather mean things about their colleagues.

It’s a pain collaborating with them because you never quite feel they are making a full effort. They give the impression the group isn’t good enough for them. They are special, while the rest of us – sadly – are not. Sly superiority can be grounded in injured narcissism. It’s a desperate, and fragile response to a nagging insecurity about just joining in and admitting that this is your gang – for better and for worse.

Ten: Non-Listening

When you’re speaking they nod; they might make an occasional note; they look at you. They go through the externals of listening. But actually, they are not paying attention to what you say. In their head they already feel they know the key things. They are just politely allowing you to ventilate. But your words cannot actually be important.

A variant on non-listening is to speak too much; it’s grounded in the same lack of curiosity about what other people think. The person who speaks too much isn’t merely hogging the conversation. They are in fact demonstrating they they are not a good listener. In their mind, listening is the inferior position, speaking is the sign of status.

It’s not surprising that listening isn’t done so well very often: we have some very powerful collective conceptions of the power of speechifying.

The flip side of this is the idea that it is slightly shameful to have to listen. One is back at school, an infant.

BETTER COLLABORATION

It’s normal, when we think about the problems at work, to think first and foremost about that highly troublesome category: other people. Their flaws are so obvious, so irritating, so hurtful…

It can therefore take a long while – but this is no sign of evil on our part – before we realise that, logically-speaking, the faults cannot merely belong to others. Slowly, a realisation dawns: we must by necessity have flaws of our own when it comes to working with others. That’s when we should start to ask some key questions: what do we think we are like to work with? What makes us troublesome? What might people be saying about us when a gossip session happens out of earshot?

These are deeply tricky questions. Our self-love, that coating of protection we need in order to drag ourselves through life, generally resists such unpeeling. And yet, we would be wise to go in for enquiries of this sort, because we’re always likely to be one part of what makes any collaborative activity go well or badly. Furthermore, we have unique access to ourselves. We don’t have to ask anyone permission or worry about issues of seniority. We can start right away – and feed back to ourselves without fear.

But to begin the process, we have to relax, which means legitimating the idea that everyone, and that includes us, is a little crazy and damaged. And that’s very much OK. Our madness and eccentricity is a given, and no sign of pathology. Of course we’re hard to work with and quite tricky. We’re human. The issue isn’t whether or not we have problems. It’s just a case of determining which ones we have – and then trying to do something, ever so modest, about improving them.

What flaws do you think you have…?

Take the list of the 10 immaturities and grade yourself against them from 0 to 10.

Whenever you go over a five, stop and reflect.

Then tell us/yourself a story about when you were immature in collaborating… – and what happened.

Where did the difficulty come from in your character? What were you scared about?

How does your immaturity relate to your past?

The Theory of Transference

What makes each of us hard to work with is that we carry certain rather unhelpful ideas around with us about what other people are going to be like, how they will behave towards us, and what will happen when we say and do a variety of things.

We all have a ‘history’ that unbalances our responses to the presence. It heavily predisposes us to interpret current reality in certain ways, and to twist the evidence according to a narrative that feels familiar – but may be deeply unproductive for everyone concerned.

The task of emotional maturity at the office means getting on top of one’s history, realising the exaggerated dynamics one is bringing to situations and monitoring oneself more accurately and more critically so as to improve one’s capacity to judge and act on situations more neutrally and sensibly.

The origins of our distorted behaviour patterns lie in something known as transference – a psychological phenomenon whereby a situation in the present elicits from us a response – generally extreme, intense or rigid in nature – that we cobbled together in our past, in childhood to meet a threat that we were at that time too vulnerable, immature and inexperienced to cope with properly. We are drawing upon an old defence mechanism to respond to the difficulties of adulthood.

In most of our pasts, when our powers of comprehension and control were not yet properly developed, we faced difficulties so great that our capacities for poise and trust suffered grievous damage. In relation to certain issues, we were warped. We grew up preternaturally nervous, suspicious, hostile, sad, closed, furious or touchy – and are at risk of becoming so once again whenever life puts us in a situation that is even distantly evocative of our earlier troubles. Perhaps we had chaotic, unreliable parents whom we dealt with by rigidly organising our room, arranging books by size, and reacting with alarm at the slightest bit of dust – and even now, outer disorder ushers in a panicky feeling within that everything is out of control once again. Or we had a sister who was always late to events that mattered to us, or a mother who was both humiliating and obsessed by fashion.

The outer world is constantly putting in front of us situations that are relatively ambiguous and look quite a lot like ones from the past. Unfortunately, the unconscious mind is very bad at distinguishing the present from the past, and reality from ambiguity.

Because transference happens without us knowing it, we generally can’t explain why we are behaving as we are. We carry years behind us that have no discernible shape, which we have forgotten about and which we aren’t in a position to talk others through in a manner that would win us sympathy and understanding. We just come across as a bit weird or extreme in certain areas.

Key to building up emotional maturity is working out where transference might be occurring. To do this, we have to ask ourselves a lot of questions, in private, or perhaps with the help of a coach or therapist.

We can get a sense of the weight of the past on the present by considering ‘transference exercises.’ The most famous of these is the Rorschach test, devised in the 1930s by the psychologist Hermann Rorschach to help people to learn more about the contents of the hard-to-reach parts of their own minds. By being shown an ambiguous image and asked to say what it was, Rorschach believed that we would naturally reveal some of our latent guiding fears, hopes, prejudices and assumptions.

The important point in any Rorschach test is that the image has no one true meaning. Different people merely see different things in it according to what their past predisposes them to imagine. To one individual with a rather kindly and forgiving conscience, the image below could be seen as a sweet mask, with eyes, floppy ears, a covering for the mouth and wide flaps extending from the cheeks. Another, more traumatised by a domineering father, might see it as a powerful figure viewed from below, with splayed feet, thick legs, heavy shoulders and the head bent forward as if poised for attack.

Or take another classic transference exercise:

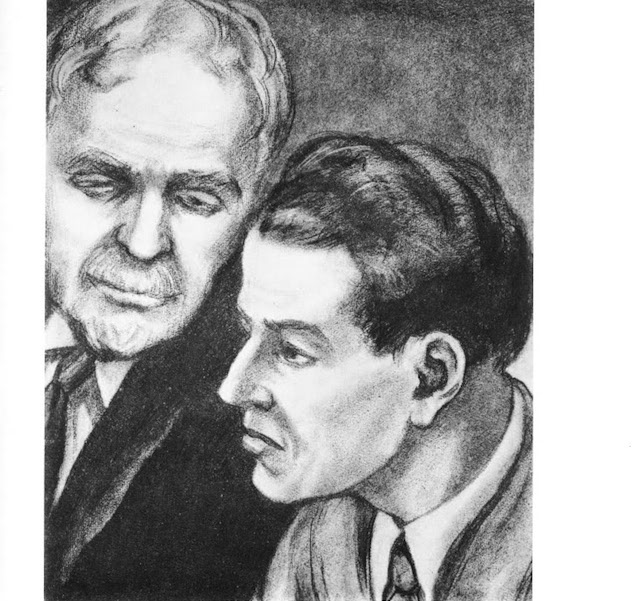

It’s key that this image is ambiguous. You can read it many different ways, and that’s the point: to make you aware of your characteristic instances of transference by teasing them out with an inconclusive image.

Of this image, people might say things like:

It’s a father and son, mourning together for a shared loss, maybe they’ve heard that a friend of the family has died.

It’s a manager in the process of sacking (more in sorrow than in anger) a very unsatisfactory young employee

Or: I feel something obscene is going on out of the frame: it’s in a public urinal, the older man is looking at the younger guy’s penis and making him feel very embarrassed.

One thing we do know – really – is that the picture doesn’t show any of these things, it simply shows two men rather formally dressed, one slightly older. The elaboration is coming from the person who looks at it. And the way they elaborate, the kind of story they tell, may say more about them than it does about the image. Especially if they get insistent and very sure that this is what the picture really means. This is what one means by transference.

A third transference exercise asks us to say the first thing that comes to mind when we try to finish certain sentences. For example:

1. Men are generally…

2. Women are almost always…

3. When I fall in love, what’s bound to happen is…

4. When someone I care about is late, it must be because…

5. The kitchen is in chaos, and it’s evidence that…

6. When I hear someone described as ‘very intellectual’, I imagine them being…

Because these sentences aren’t about a concrete situation in the present, the only way to answer them is by calling up transferences from the past. Our responses hence give us a clue as to a bias in our minds that would normally be invisibly applied, merging imperceptibly with the dilemmas of the present.

Mature people are ready to accept that they might be involved in multiple transferences. Ideally, we should all rationally disentangle and un-distort our transferences and explain them to others in good time. But it rarely happens and collectively we pay a big price for our ignorance. We keep making things tough for everyone by over- and under-reacting – and so our work relationships are far harder than they need to be.

Let’s consider the key areas of professional psychological distortion – and try to suggest some questions and exercises that can get us thinking more fruitfully about why we react the way we do:

1. Defensiveness

Defensiveness tends to be the result of having internalised the voices of people in our past who judged us very severely and left us feeling not just that we did this or that problematic thing but far more catastrophically: that we might have been purely and simply ‘bad’. For the defensive among us, it doesn’t take much to be reminded of our proclivities to feel attacked. The slightest complaint can take us back to the original trauma. It’s therefore key to try to trace back the critical wound to its source – so as to develop a capacity to separate what belongs to the past from the give and take of office life today.

Berthe Morisot, Le berceau (1872)

However robust we may appear to others as adults, we all have a profound history of vulnerability. A baby is so small and delicate (though it can scream its head off if it doesn’t get fed), it’s worth pondering on its basic helplessness – and feeling a moment of compassion towards it and ourselves. We were all once hugely dependent on other people for our needs: we couldn’t speak or explain what we wanted, we had to rely on them to understand us, soothe us and be kind to us… Some of us enjoyed the touching care evoked by the painting above by Berthe Morisot – minus the mosquito net over the bassinet, perhaps. Some of us were not so lucky.

It’s not surprising, therefore, if those among us who weren’t quite so carefully nurtured sometimes get a little extreme in our responses to attack, if we become – as the phrase goes – a bit defensive. There were once so many ways we could get seriously hurt and we had to develop some ways of defending ourselves as best we could. Our minds had to get used to being on high alert, always on battle stations, waiting for the next attack to come over the horizon. Anyone could have been the enemy. This becomes a plausible stance when you’ve been let down by someone you should have been able to rely on absolutely. It’s not surprising if, in adult life, some of us find we’ve built up a set of habits somewhat out of proportion with the threats we actually face, if we bridle at the first hint of criticism – not because we are bad, but because it feels like this is the start of major assault and we would be running an intolerable risk were we not to strike back immediately.

The habits have become rather a liability now, of course. People get upset with defensive behaviour, and promotions aren’t handed out so readily to those who, at the first hint of criticism, flare up, but we didn’t get like this without some good reasons – reasons which we should (in calm moments) strive to trace back to their origins, fully understand and gently try to overcome.

– In the past, did you receive the support you needed?

– Who let you down?

– How and when?

– Did a person’s criticism ever help you solve a problem?

– How might you have criticised yourself if you’d needed to?

– What would it feel like to be a friend to yourself?

– Imagine you are your boss. Try to criticise your work but not who you are. What would you need to hear?

To recognise – without shame – and understand sympathetically, why one has become defensive is the key to unwinding the habits of excessive self-protection. We need to see that we’re warding off dangers that were experienced as very real in the past, but which don’t actually threaten us anything like so much today. We needed those defences once. Now we can afford to let them go. We’re truly strong, strong enough not to need to greet the world with armour.

Consider this little School of Life film, which lightly sends up the difficulties associated with being over-defensive.

2. Irrational Rivalry

Early on, there must somehow have been a feeling that there wasn’t enough love to go around. So we learned to compete, and to worry about anyone else who might be in a position to hog the attention more properly due to us.

– Who was a difficult rival for you early on?

– Whose attention or approval were you competing for?

– How did it feel when you thought you were being rejected, overlooked or sidelined? How did you react?

– From the perspective of today, how do you think that person really saw you – and how did they see your rival?

– Was there anything that could have reassured you at the time?

Next, perhaps consider this picture by Pierre Prud’hon: Portrait of Rutger Jan Schimmelpenninck and Family

They all look kind, charming and reasonable. But imagine that the children are in the grip of irrational rivalry. The boy is obsessed with the idea that the girl gets more love from the father. The girl knows the mother prefers the boy.

The parents are sure that there is enough love and attention to go round; they feel they are being careful to be fair, not to have favourites. But this may not be at all how the children experience things. Love, they feel, is a finite resource and they aren’t getting enough. If this has been a big issue in our own development, then as we grow older, we are liable to bring this pattern of experience to lots of apparently very different situations. So at work, it can feel as if there is direct competition for the approval of ‘the grown ups’ – anyone more senior in the organisation.

A fix involves a shift of focus. In the picture we can pay attention either to the children or to the parents. Look at the children for a moment. Take in their faces. When we’re focusing on them, of course we can understand how rivalry gets established. It’s totally unsurprising they might feel that way. But we can equally focus attention on the parents. When we do that, we see how unnecessary and tragic the rivalry actually is, because the children are not in fact competing for affection. The parents are full of love. The struggle isn’t real.

When we feel drawn into excessive rivalry, we should shift attention from our own longings to the point of view of those we are appealing to for affection, esteem, promotion, money. What we have to ask ourselves is: are they in fact keen to reward only one person? Or would they much rather (as good parents do) have two lovely, healthy, strong successful ‘children’/office workers? Does it make sense from their point of view to allow only you OR your rival (but not both) to succeed?

3. People-Pleasing

Somewhere in the past, saying what you felt seemed very dangerous indeed. People-pleasing has its roots in a feeling that you could not be both truthful and loved. Who you were was not enough. You had to dissemble and lie and try to humour someone who appeared distracted, angry, irrational or mean. You were not allowed to be the focus of your own world when you needed to be. You had to find a way to cope – and you did it by attempting to find out what every person you dealt with wanted, and then trying – desperately – to give it to them.

In one of his plays, Shakespeare gives a quick sketch of just such a formative experience.

Sometimes it feels too dangerous to tell the truth

At one point in Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra – Act II Scene V – a poor messenger has to tell Cleopatra that her lover, Antony, has spurned her and married someone else. The queen offers the messenger a fortune to say it’s not so …

Cleopatra: Say ’tis not so, a province I will give thee,

And make thy fortunes proud.

Messenger: He’s married, madam.

Cleopatra: I’ll unhair thy head: She strikes him

Thou shalt be whipp’d with wire, and stew’d in brine,

Messenger: Gracious madam,

I that do bring the news made not the match.

Cleopatra: Rogue, thou hast lived too long. Draws a knife.

Shakespeare is showing us a terrifying version of the person who makes it very hard for you to tell them the truth. When you’ve tried to tell the truth and been almost killed for it, it isn’t surprising if you become a bit more careful next time and slowly turn into a people-pleaser.

– What important figure in your early life were you afraid of upsetting with your truths or your being?

– What happened if you were just ‘yourself’ and honest with them?

– Where, today, does this kind of danger lurk for you? Who are you afraid of upsetting?

– What would actually be likely to happen if you told them the truth?

– How bad would that really be?

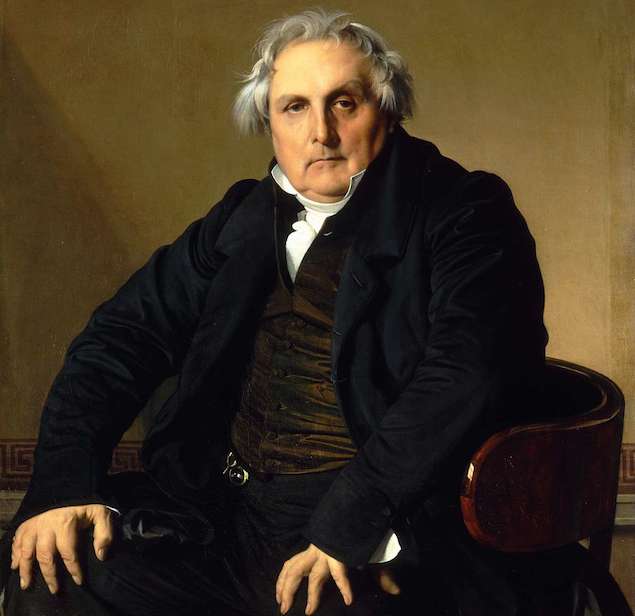

Everyone could draw their own portrait of the intimidating individual

Some of us grew up around intimidating types a little like the man in the portrait above. You felt you had to be incredibly careful around them. You were walking on eggshells, terrified of setting them off. They had to be kept in a good mood as much as possible. It could have been an irate father, an overwrought mother, an explosive elder sister; a teacher who seemed to have it in for you; or a harsh early boss. Whomever it was, a pattern of anxiety was laid down. One grew extremely aware of the dangers of upsetting people.

Once we get more conscious of how this way of seeing others got started, we can begin to sense that – probably – it’s not really called for so much in our lives today around the office. Without quite noticing it, we may be sticking with an unfortunate habit that was formed – very understandably – to deal with a big problem that belongs very much in the past now, ten or fifteen years ago. It’s a tragedy of emotional life that certain habits have a tendency to stick around even though the situation that originally gave rise to them may have long since changed.

We need to be firmer in ourselves. We’ve adopted an ideal of being pleasing which is in fact not pleasing to anyone in the long term. Put yourself in the shoes of those you’re afraid of. Is it really so nice to be sentimentally lied to? People need to know the bad news to fix it. What small bit of the truth could you start to share with those who run the business everyone wants to see succeed?

4. Negativity

We learn to be negative when life seems to teach us that hope and aspiration are unrealistic and dangerous. And there are definitely times when absorbing a negative stance seems the mark of open-eyed realism and maturity.

– What really disappointed you in the past?

– What was the hope that got crushed?

– What do you deeply wish could have turned out better than it did?

– What are you afraid of when you hope?

– What might happen if you tried and didn’t succeed?

Getting your hopes up is a very bad idea

Sometimes, life really is pretty harsh. At particular times, in specific places, supposing that things can easily get a lot better can be a naive delusion. It’s the danger of focusing on what you want to happen, instead of preparing for what’s likely to happen. There are lots and lots of cases where people come unstuck because they didn’t factor in the potential down-side. So, negativity makes a lot of sense. There are hopes we really would be wise not to nurture.

The pictures above and below are by the Swiss-American photographer Robert Frank, who travelled around the United States in 1957, taking images for what would become a very famous book called The Americans. It shows us the often bleak reality of a country whose self-image is of relentless positivity.

Given the real landscape of our lives, is it such a wonder that many of us grow a defensive shield of pessimism and negativity? Can we not be forgiven for failing to greet pitiless reality with a smile?

Don’t get your hopes up around here

The thing is: it’s not that always sensible to hose down hope. An attitude of pessimism may really have been needed at key times in our lives, but it isn’t always a requirement. It can keep insisting that we prepare for the worst when, actually, the circumstances are replete with genuine opportunities for those who can bear the vulnerability of hope.

5. Bluster

Sometimes, we get it into our heads that concern with detail is how one loses sight of – and connection with – the important and serious things.

– Did anyone close to you fuss quite a lot in the past?

– Was anyone a bit pedantic (though that might not have been the word you’d have used at the time)?

– How were such people regarded by you and others?

– In your experience, what happens when people are too fussy?

It’s really to be expected that encounters with unimpressive, irksome fussy and pedantic people will leave us with a negative impression of the value of looking after the details.

The fix is to revise our conception of what is important – and specifically of the relation between the little (apparently minor) things and the big picture issues. The largest waterfall in Europe is in Switzerland, on the river Rhine at Schaffhausen. In the 19th century, it was one of the most prestigious subjects for painters, because it represented extraordinary energy, drama and grandeur. Turner painted it around 1805.

J.M.W. Turner, The Fall of the Rhine at Schaffhause (1805-6)

But much to the surprise of certain critics, Turner didn’t just concentrate his attention on the obvious major facts: the cliffs, the water thundering over, the spray. He also took great care to paint accurately a couple of wicker baskets in the foreground; he depicted the neat way some white packages had been tied. What was he doing. Why did he bother with such things?

The explanation was delivered by Turner’s great advocate, John Ruskin, who formulated the principle of The Task of the Least: ‘the minutest portion of a great composition is helpful to the whole. It certainly does not seem easily conceivable that this should be so. But it is the fact.’

The little details don’t distract from the big effect; they are essential to creating it. The thundering effect of the water is enhanced by including a humble, static object like a basket and a parcel. By attuning the eye to precision, the artist is priming us to be more responsive to the swirling chaos of the falls. The details aren’t a distraction from the grand effect, they help cause it.

In a limited arena on a canvas, Turner is making a case for keeping an eye on the task of the least. We should pay attention.

6. Over-Control

The desire to control springs from the natural response of a competent, energetic person to the imagined lesser abilities of others. In some situations that perception is bang on target.

– Fill in the rest of the sentence: when it comes to working properly, most people are …

– Did your early caregivers trust others? Did they trust you?

– How competent were your parents? Could you trust them to get it right?

– Did your parents trust other people?

– Where do you think your negative assessment of others’ potential came from?

– Describe an early success around taking charge of some task that others clearly couldn’t manage through incompetence.

– What often happens when you try to get others to help with a task?

– Could you ever teach people to be better at the tasks you want to help them with?

Competence is not universally and equally distributed. Some people really are a lot more on the ball than others. And it’s no bad thing if they take the lead in organising how things should be done. We ramp up our demand to have control and to have things done our way in response to some well-grounded worries about how things are currently going.

Throughout the 1970s, a number of UK car factories – particularly one at Longbridge, in the south of Birmingham – earned a reputation for low-quality workmanship, inefficiency and poor management.

If you spent a lot of time around such places and people, you could justifiably come away with the opinion that a lot of people really are pretty incompetent. You might well reach the conclusion that you, personally, could to a lot better if you just managed everything yourself.

Panicked impatience makes sense in a world of wasteful incompetence

The question, though, isn’t whether being controlling is ever a good idea. Sometimes, clearly, it is. But it depends: we’ve got a marked tendency for our instincts to be governed not so much by what actually confronts us today, but by what we became most familiar with at formative points in the past.

If – to pursue a thought experiment – Margaret Thatcher had spent a lot of the 1970s around the Swiss National Railways she might have arrived at different conclusions about the average levels of human competence. She might have learnt to trust that an entire team could be galvanised to be competent and efficient, from the signal controllers in Basel to the station master at the remote outpost of Ennetbürgen in central Switzerland. It all depends on the skills of managers at generating an atmosphere of community and collaboration. Talent isn’t only ever the preserve of just a few: with the right structures in place, it can be a resource of the many. It may be time to exchange the trauma of Longbridge for the faith and hope animating the SBB team.

7. Secret Manoeuvring

Going behind other people’s backs doesn’t sound very nice when stated directly. But it was not an unreasonable strategy in many of our pasts. From particular situations, we may have developed the ways of operating that can be summed up with the term ‘secret manoeuvring’.

– When you were young, who was it not worthwhile ever trying to talk to or change others?

– What do you imagine they would have done if you’d tried?

– When someone has done something wrong, is your impulse to a) say something b) leave it and move on?

– Do you sometimes feel that people betray you? What do you do?

– How do you think people will respond if you tell them you have an issue with them?

– Suppose someone on the team seems to be a little less bright and determined than you thought: what do you do?

Secret manoeuvring is a vote of no-confidence in the power of persuasion or education. We resort to behind the scenes arrangements because we’ve had some bad experiences in which our intentions have met with blank stares or hostility and people have refused to change their ways when we attempted to tell them how we felt. We have somewhere in our deep minds drawn a big conclusion: there’s no point in arguing and directly dealing with people.

Under pressure and not sure of other people

When he was Prime Minister, Gordon Brown developed a reputation as someone who was more than usually willing to deal with colleagues by subterfuge rather than face-to-face dialogue. He reportedly deployed his private office to undermine the position of cabinet ministers who were – to the public eye – his personal appointees. Rather than convince his colleagues in discussion, or directly assert the authority of his position, he would allegedly give off the record instructions to special assistants he had installed in the relevant civil service department, thus effectively (but secretly) cutting ministers out.

If this picture is accurate, the motives for acting in this underhand way need not be entirely sinister. In fact, the ambition is poignant and touching. Gordon Brown was a prime minister with an overwhelming sense of duty and responsibility to the nation, someone who felt he was under great pressure from rivals and from the opposition parties. He also felt that most other people were not quite up to scratch. So in order to get into action the policies he truly believed were in the public interest, he would have felt he had no option but to resort to subterfuge. He had desperately little confidence in his own power to cajole and chivvy his major colleagues; he lacked the maturity to trust in his own ability to gradually draw the best out of people. He felt he had no choice but to go behind their backs – and make it all happen as it should, without quite talking about it. He was acting disastrously, for the best of reasons…

8. Unfriendliness

In theory, of course, everyone wants to be friendly. But, we can grow up feeling that friendliness (and what goes with it – trusting, niceness, sharing) is too costly. It can simply look like it’s the wrong strategy for success.

Exercise:

– Which person from your past gave you a sense that nice guys don’t finish first?

– What do you worry could go wrong if you took the time to be friendly?

– What happens to nice people, in your view?

We’re not unfriendly because we’re mean or inherently misanthropic, but because niceness has come to seem weak and indulgent. Partly, that’s a matter of prestige. A lot of successful people seem in a great hurry and are rather brusque, and we therefore pick up from them the suggestion that success is dependent on a brutal manner.

What we need to be exposed to are examples of friendliness working in synch with professional success. From 161 to 180 AD – the period he ruled as an exceptionally conscientious Roman Emperor – Marcus Aurelius was officially the busiest man in the world. At any one time he might be fighting off Germanic tribes on the north-east frontier while dealing with incursions by the Parthians in the south east; attempting to control the currency of the imperial economy; acting as the highest judge and simultaneously reforming major areas of the legal system.

Marcus Aurelius was, by temper and character, inclined to be brusque and dismissive. He was enraged by time-wasters. But he knew in his heart that this wasn’t the way to go. So he tried hard to train himself to temper his irritations with others: they were not, he told himself, wicked inherently so much as sometimes lazy and expedient, as he could be. In his Meditations he wrote rules for himself:

When you wake up in the morning, tell yourself: The people I deal with today will be meddling, ungrateful, arrogant, dishonest, jealous, and surly. They are like this because they can’t tell good from evil. But I have seen the beauty of good, and the ugliness of evil, and have recognised that the wrongdoer has a nature related to my own—not of the same blood or birth, but the same mind, and possessing a share of the divine. (II. 1)

He also reminded himself of attitudes he admired. He thought a lot about one of his mentors, a man called Sextus who, he wrote, had

a benevolent disposition: gravity without affectation; able to tolerate ignorant persons and those who form opinions without consideration. He had the power of readily accommodating himself to all; he could express approval without noisy display; he possessed much knowledge without ostentation. [Meditations, book I]

Because, like us, he was tempted to be unfriendly, Marcus Aurelius reminded himself on a daily basis that it is entirely possible to be serious, focused and efficient without coming across as rude or unconcerned. If the effort was important enough for him, it should surely be important enough for all of us.

9. Slyness

The feeling that the people around you don’t actually deserve your full commitment and loyalty doesn’t sound very nice. We’d like to think of ourselves as always ready to give our best. But sometimes a person can easily be forgiven for feeling that their colleagues don’t actually deserve much respect.

To cope here, you’d probably need to get a bit sly

The reason we end up being a bit sly is because full participation doesn’t present itself as attractive enough. We’re sly when we feel we’d rather not be part of the team. We need to feel a little more special than others.

– How are you different from others?

– In the past, who made you feel special?

– Did that feeling of specialness come under threat at some point?

– Who was hard to please (but you wanted to please them)?

– What are groups typically like?

Not everyone in that group is perfect, but they’re good enough… and they’re better for being part of the group

This painting, by Rembrandt, might help. Imagine you are with them, part of the night watch. You’re going out on a dreary night to interfere with drunks, move on the troublemakers and keep an eye out for thieves and burglars. It beats being at home, because you’re doing it with other people. Those in your team, admittedly, won’t all be your ideal companions or colleagues. Some might be a bit self-regarding, others a bit timid; some are bossy, some are weak. The Night Watch speaks of the appeal of joining in.

These people are heading out to patrol the streets on a wet night. But it’s an inviting image. And it would probably be nice to join in if we could. Companionship can be so much better than an isolated, fragile sense of being distinctive. The message of the picture isn’t that the members of the team are all wonderful in and of themselves. But, rather, that it is still worth joining in because a team has something that any one individual won’t: it ennobles all those who take part.

10. Not listening

We can easily get impatient with a person who doesn’t listen – but not-listening can have honourable origins. Even though it becomes a problem when we need to collaborate, not listening doesn’t always originate as a failing. At some moments in development, not listening is key. There may be so many voices, so much noise that can threaten to submerge us, it is a survival strategy to close the doors and focus on a single voice you need to hold on to and have a responsibility towards: your own.

– When was your voice stifled?

– Were you listened to as a child?

– When did you feel you had to listen to someone else a lot?

– Are you heard enough?

– When do you feel that what another person is saying is very unhelpful to you?

In 1973, the American literary critic Harold Bloom published a seminal book of criticism titled The Anxiety of Influence. In it, he describes how many great writers have suffered from an anxiety about listening too much to the voices of their predecessors. The artists of the past teach us how to write and feel, but they also – unwittingly – often threaten to silence the creative potential of the present moment, through their sheer eloquence and brilliance. They stifle our own nascent sensibilities. In Bloom’s view, only a few writers in any generation ever manage to escape from the unhelpful impact of their predecessors – and go on to produce something which is properly distinctive. Interestingly, says Bloom, these path-breakers do so by a rather odd- and suspicious-sounding strategy, which we can nevertheless learn from. They shut out the voices of others; they acquire the art of not listening.

Bloom might have been writing primarily about poets of the early modern period, but his theory can be extended beyond the production of art. The story he is telling is simultaneously that of every human’s journey to maturity. In order to find your own voice, you do need – for a while – to bracket and silence the louder, more persuasive voices of those who have come before you. Culture provides us with a very reasonable account of why for all of us, at times, not-listening is likely to be a noble and important strategy.

Not-listening takes root in situations where there’s a genuine tussle, a real conflict between either taking in the points another person is making or exploring and developing your own insights. At certain moments, especially in childhood or at the beginning of a creative endeavour, this is the tussle we face. But – as with so many of our unhelpful behaviours around groups – we don’t have to stay stuck here: we can move beyond the vulnerability that first led us to adopt a particular and costly ‘defence’. We do not have to keep on always behaving as if we remained in the dangerous situation that first required a defence. We can, with effort and sympathy for ourselves, take a few modest steps towards opening our ears to the voices of others, ever more secure that our own distinctiveness will – once the meeting or chat is over – continue unscathed.

***

Growing up isn’t ever quick, or really quite done. But to study these ten possible areas of immaturity signals a start of a journey towards solving some of the issues that bedevil office life and poison some of the most precious opportunities of our lives.

Find out more about the way the School of Life works with organisations:

http://www.theschooloflife.com/london/business/professional-development/