Work • Consumption & Need

Consumer Education: On Learning How to Spend

Society takes the business of making money very seriously indeed. Much of our education system is geared towards giving people the skills to get a good job and a steady income.

By contrast, very little attention is given to how to spend money well – by which we mean, in ways that stand a chance of properly increasing our sense of well-being and therefore justifying the sacrifices that went into earning the cash. The very subject sounds slightly absurd. Surely there is no challenge here, other than making sure we have enough (by which we mean, ever more) in our wallets.

In the developed world, true basics like shelter and food require only part of an average income. An important slice of consumption is therefore directed at things we don’t absolutely require. Some of the time at least, if we properly reflect on our experiences, this discretionary expenditure doesn’t quite bring us the satisfaction we were hoping for. Certain of the more spiritual voices will argue that the reason is obvious: the whole idea of improving our lives via something one can purchase is fundamentally misguided.

But there’s another possible explanation: that material things can contribute to satisfaction only if we understand ourselves pretty well. Spending successfully is something we need to learn. We need to undergo a process of Consumer Education, simply defined as the art of better understanding the links between what we spend and how we feel.

Why does consumption often go wrong? In part, because we don’t take our own feelings seriously enough. It’s odd – even a bit offensive – to suggest that we may not always have a very secure grasp on what we’re actually experiencing; that we could be doing things like buying technology, eating in restaurants, going travelling or choosing outfits and not sincerely be registering our emotions.

Yet, we are arguably often very lax about tracking what we experience. This kind of inattention is perhaps easiest to spot in the visual realm. A lot of the time, we see without properly noticing. Our eyes are alive to the broad features of the places we wander through, but our vision isn’t focused. That’s what can make art so powerful when it jolts us out of our customary visual lethargy.

Noticing all we don’t normally see.

On seeing what the German painter Albrecht Durer perceived in an ordinary patch of wild grass (in a watercolour from 1503), we can sense the difference between focused and casual attention. Durer took note of every blade of grass, and every nuance in the colour of the soil. We don’t need to be great artists to pay closer attention to the data from our senses. The core move of redirecting attention can be repeated in any realm of thinking or feeling, and – in this context – in the area of consumption. Take, for example, a holiday. We are never trained to study our own responses to a trip, in order to determine how we really felt over a nine-night span and what this tells us about who we are and what we need. We don’t feel we can learn much about ourselves from tracking the peaks and troughs of our moods: and don’t strive to adjust our spending patterns in relation to our feelings. Instead, we bump into our pleasures slightly by accident and don’t take either our boredom or our joys as seriously as we might – which makes us vulnerable to never refinding the ingredients of our own satisfactions.

One of the big claims of modern capitalism is that it provides us with unrivaled consumer choice. Yet we are hardly encouraged to dwell too long on our subjective sense of well-being in relation to purchases. There’s an extraordinary diversity of products. It can seem as if every possible nuance of preference has been carefully catered for. Yet under the surface of this seeming individuality, consumer patterns are surprisingly standardised. Probably you will have bought a certain sort of flat screen TV in the last few years. You are very likely to buy into one of the major phone brands and update it when you are told. You are likely to have taken at at least one trip overseas last year: you probably went to either a beach or one of 12 famous cities around the globe.

None of this will feel like a diminution of anonymity, or the expression of what might (a little brutally) be called herd-instinct. Until one puts these personal free choices into historical perspective.

You are very unlikely to possess a ruff and a dress sword – though left entirely to your own devices there is no particular reason why should shouldn’t fancy the idea.

No matter how rich you are, you are unlikely to covet a sedan chair carried by two servants wearing wigs – though this was a very big and common aspiration across Europe in the 18th century, and it could still prove a highly convenient way to move about a large garden or golf course.

We are so easily able to identify the era of a photo or a painting precisely because patterns of consumption (the things people possess) exhibit large collective patterns which tend to radically circumscribe individual preferences.

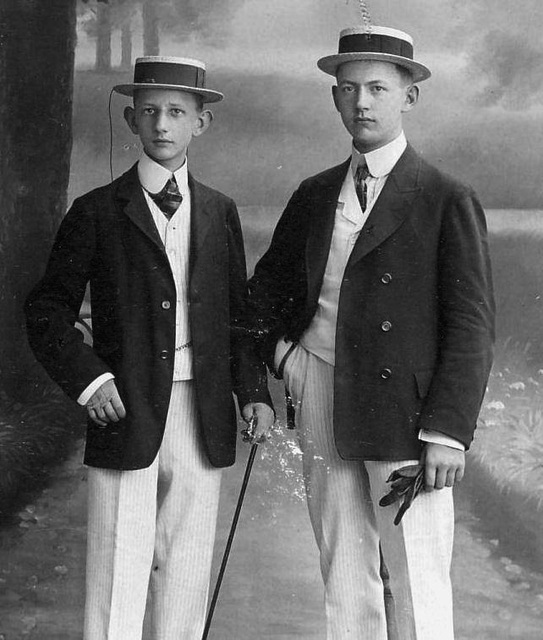

Their tastes, or the tastes of their ‘herd’?

It’s not just an astonishing co-incidence that these German youths ended up (in 1909) wearing almost identical clothes. They are – instead – evidence of a profound fact about human beings: to a very large extent, we buy according to what others are buying.

But why is there such uniformity in purchasing decisions? How come everyone seems to like many of the very same things at the same time? It’s not strange that we’ve got a bias in this direction. The instinct to follow what other people are doing is a reliable guide to survival for almost everyone outside of a modern society. You have to stick with your tribe; you have to learn to do what the elders (who have clung to life) are doing. You have to be ultra cautious about novelties and individuality because there’s so much catastrophic danger around. We learn to speak by speaking like others. We learn to be part of a team by modelling our behaviour on that of others. It’s only very very recently – yesterday in terms of the history of the human brain – that more than a tiny faction of people have had any opportunity to buck a trend, and stand out or pursue a markedly individualistic style – with that being a good idea.

So we should expect our brains to have evolved to be highly responsive to signals about what most people are enthusiastic about (especially people we perceive as being a bit like us). We find it hard to trust something that comes without widespread support; we find it hard to resist the appeals of something that most people find very attractive.

The challenging aspect of this cognitive bias is that, in the conditions of modern capitalism, we become highly vulnerable to all authoritative and beguiling suggestions about what people in general are up to. We end up experiencing adverts as wise messages about what the tribe is doing – and we follow.

Huge commercial interests are constantly seeking to persuade us to join trends: happy people drink champagne; your partner isn’t serious about you unless they give you a diamond ring; water parks are terrific fun etc…These ideas can become compelling, even when they are not much tethered to our own reality.

It’s not that the corporations are inherently cynical or wicked. They just have to work hard to persuade you to side with them. The rewards for gaining market share are huge; the punishment for declining sales is draconian. It’s not at all surprising if they get very skilled at getting us to agree with them about what happiness might be like.

It takes a lot of strength to stand up to a trend. In mid-18th century France, the dominant artistic trend was the Rococo style. It was excited by sweetly idealised romantic scenes, prettiness, ribbons, gauze and lots of pastel-coloured flowers.

There were some moods and feelings it was very responsive to: like instances of playful flirtation.

However, the dominance of the Rococo made it very much harder to recognise the appeal of things which didn’t quite fit its template. One person who held on to his own sources of satisfaction was the painter Chardin. He liked quiet, modest and rather serious domestic scenes. He didn’t like flirtation and bucolic gardens.

Because he didn’t fit the trend, he was sidelined for many years. But Chardin was very determined and stuck strongly with his preferred approach – even though it meant great financial penalties. However, quite often we’re not as dogged as he was; we don’t relish battling against the dominant trends of the age.

That’s why the proper process of consumer education starts in a somewhat unusual place: with training on how to focus on the sources of our real satisfactions and in how to hold on to these even when they lack external validation and prestige. It might involve the confidence to know (as Chardin did) that we like quiet domestic interiors when everyone else likes nymphs in pretty gardens, or to realise that foreign holidays or fusion restaurants or a certain kind of smartphone really aren’t for us, whatever our social circle and the adverts we pass on the way to the station would dictate.

We need to become better students of our own feelings of happiness. It’s often the case that we seem to stumble across things that we really like – but don’t take proper note of or extrapolate the principles behind our pleasure. For example, late one evening, we might find ourselves having one of the most interesting conversations of our lives. But we can’t quite discern why it happened. It’s put down to luck and the search for how to create such a feeling again is abandoned. Or we have a terrific afternoon one weekend walking down an old canal, finding a series of abandoned warehouses, which seem to nourish an interest in the history of industrialisation. The activity has no prestige and on our next holiday, we are led – like a leaf in a powerful current – to go to Rome, where the guide book directs us to a succession of churches, which we find rather boring (if we are honest, which we aren’t so much).

We are fatefully resigned to the idea that some very good, very pleasurable, things just happen ‘on the spur of the moment’ or by chance – or are simply matter of luck. But this is precisely where the whole process of consumption starts to go wrong. We are failing to take our moments of happiness seriously enough.

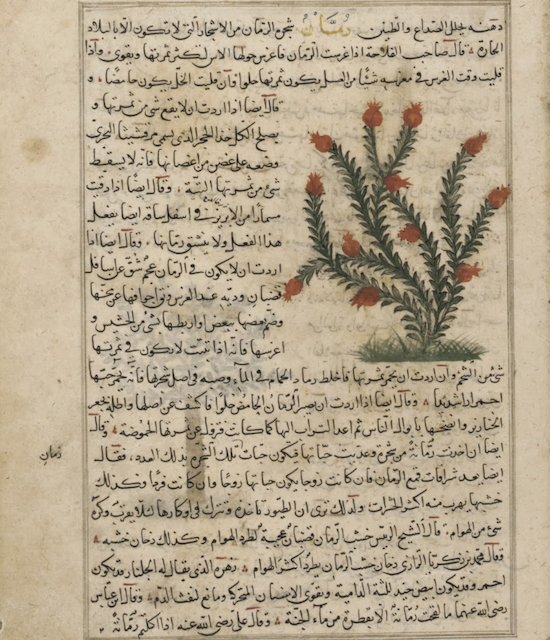

Over time our culture has developed a very different attitude to at least one area of pleasure: the pleasure of eating – with incredible results. A recipe book is a compendium of rules for reliably re-creating a very particular sort of pleasure; and we have so many by now that the human race can be said to have achieved perfect mastery of the pleasures of the palate. Perhaps the world’s earliest recipe book is called The Book of Dishes (1226) by the Arabic author al-Baghdadi. It tells us in meticulous detail how to make lemon chicken, pomegranate juice, stuffed vine leaves and olive and goat stew.

How to recreate the pleasurable feeling of pomegranate juice

Recipes are typically undaunted by the fact that the process of reproducing a pleasure of the palate might be a bit complex, might sound odd to traditionalists, might require special equipment and might have to be rather precise at certain points. This is in dramatic contrast to the way we tend to let other (actually very important) pleasurable experiences rest on chance or simply die in the privacy of our hearts.

To come to our central thesis: a recipe – in its most ambitious version – shouldn’t be confined to food. We should become the authors of our own recipe books of pleasure. In our private, individual recipe books, we should note what we like, what ingredients were necessary to produce it and therefore, what money and practical arrangements we will in future require in order to recreate the feeling. We need to overcome our surprising haphazardness when it comes to identifying and remembering what we enjoy doing.

If we were to focus more closely on our pleasures, most of us are in fact, what was benignly once identified as ‘original’ in the vocabulary of 18th-century England; that is, we are very individual, un-herd like in our essence. ‘Originals’ were people secure and confident enough not to worry very much what others thought of them and to let their own pleasures be the guides to their ways of life. The English botanist and naturalist Gilbert White, for instance, realised that the patient study of animals was what he liked above all (no games of cards or dancing parties for him). He therefore devoted all his material resources to tracking down his favourite species and built them nests and homes in his garden. He memorably described discovering that few things gave him as much satisfaction as lying on his stomach in his garden looking very carefully at what the local hedgehogs were up to.

If we tracked down our own equivalents of White’s hedgehogs, we might find ourselves slightly re-arranging our priorities. We could discover that many of the things we own bring us no pleasure at all, but that a few – expensive or cheap – really do make a difference and might henceforth become more focused targets of appreciation and expenditure. We would depart from the big trends in a range of areas, while delighting in them in others. We’d let our subjective enthusiasms direct us to extreme frugality in some categories and perhaps unbridled extravagance in others. Overall, our spending patterns would grow helpfully weirder.

The concept of consumer education has until now been unhelpfully confused with the idea of reviewing. Reviews are everywhere, but they are fundamentally flawed in tending always to assume that you’ve already decided to make a purchase in a particular product range and are wise to do so; you are just not sure which one to go for. You’re going to get a phone – but which one? You’ll be booking a hotel in Greece… but which one? However, what is missing from this mania for reviewing is the bigger prior question, the question of whether a purchase in this category is even necessary to your particular satisfaction. Is it worth getting a phone or going abroad in the first place? What sort of a person am I? What do I, in particular, need to be happy?

If we were better at knowing ourselves, the shape of the economy would change. ‘Business’ is nothing more than an attempt to please customers. If many businesses are only partly successful at this, it’s not the result of evil: it’s that companies don’t especially have to mind not hitting happiness targets, because a lot of money can be made via the fact that we make purchases at all – even if we don’t quite get the result we’d hoped for. Furthermore, it’s currently hard for firms to work out what to give us, given that we ourselves don’t quite know what we want. We need to get better at sending into the market the signals that would help the evolution of capitalism. We should stop going back to the hotel we didn’t quite like, or buying the same not very ideal bit of technology, or ending up in a water park, because we were unable to let manufacturers know what we’d really rather be paying for – and would happily have switched to if only it had been on offer.

We’re imperfect consumers because of a quite basic challenge of the human condition: we’re not very skilled at making ourselves happy. It’s a tragic irony that the whole point of consumerism is to please us but that on so many Sunday afternoons, on the way back from a film or a mall, the train station or airport, we may privately acknowledge that we have once again not quite been able to lay our hands on the nerve centres of our own pleasure.

Consumption is a point at which modern life dramatically intersects with an age-old issue: the origins of human flourishing. In truth, consumer education is a branch of philosophy, a study of how we can educate ourselves as to the true natures, and constituent features of a good life. The challenge of becoming the authors of our own recipe books of pleasure still lies before us.