Work • Capitalism

Artists and Supermarket Tycoons

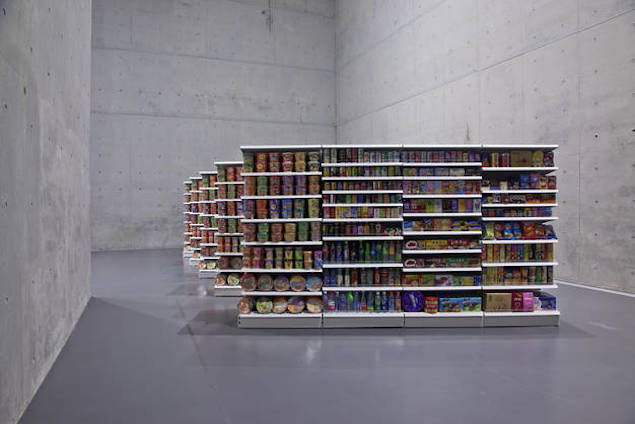

Xu Zhen’s Supermarket

The Shanghai-based artist Xu Zhen is one of the most celebrated Chinese artists of our age. He operates in a variety of media, including video, sculpture and fine art. His work displays a deep interest in business; he appears alternately charmed and horrified by commercial life. In recent years, he has become especially fascinated by supermarkets. He’s interested, in part, by how lovely they can be.

Xu Zhen loves the alluring packaging, the feel of lifting something off a shelf and seeing multiple versions of it waiting just behind and the exquisite precision with which items are displayed. He particularly likes the claim that supermarkets can provide us with everything we could possibly need; the claim of comprehensiveness.

At the same time, Xu Zhen feels there’s something really quite wrong with real supermarkets – and commercial life in general. The actual products they sell often aren’t the things we genuinely need. The backstories of the things on sale is often exploitative, everything has been carefully calculated to get us to spend more than we mean to. There’s cynicism throughout the system.

So, in response, the Chinese artist mocks the supermarket repeatedly. In his work, the products on the shelves look real, you’re invited to pick them up, but then you find out they are empty, as physically empty as Xu Zhen feels they are spiritually empty. His checkouts are similarly deceptive. They seem genuine: but you get a receipt and it turns out to be a fake; you’ve bought ‘nothing’ of value.

The supermarket installation takes us on a journey: at first it is getting us to share the artist’s excitement around supermarkets and then it’s puncturing the illusion: it’s all a big, deliberate let down: the products look tempting but they are full of nonsense and don’t really nourish us.

It’s highly significant that Xu Zhen’s critique of supermarkets is ironic. We tend to get ironic around things that we feel disappointed by but don’t feel we’ll ever be able to change. It’s a manoeuvre of disappointment stoically handled.

A lot of art is ironic in its critiques of capitalism; we’ve come to expect this. It playfully hints at what is wrong but has no real clue what to do in response. A kind of hollow sad laughter seems the only fitting response. Criticism melts into irony.

Xu Zhen is trapped in the paradigm of what an artist does. A real artist, we have come to suppose – and the current ideology of the art world insists – couldn’t be enthusiastic about improving a supermarket. He or she could only mock from the sidelines. We’ve nowadays fortunately loosened definitions of what a ‘real’ man or woman is meant to do, but there are still strict social taboos hemming in the idea of what an artist is allowed to get up to: they can be as experimental and surprising as they like … unless they want to run a supermarket or an airline or an energy corporation – at which point they cross a decisive boundary, fall from grace, lose their special status as artists and become the supposed polar opposites: mere business people.

We’d like to take Xu Zhen seriously, perhaps more seriously than he takes himself. Beneath the irony, Xu Zhen has the ambition to discover what an ideal supermarket might be like, how it might be a successful business and how capitalism could be reformed. Somewhere within his project, he carries a hope: that a corporation like a supermarket could be brought into line with the best values of art: psychological and spiritual importance, kindness and wisdom.

***

Thousands of miles away from Shanghai, in the flatlands of East Anglia in the northeastern tip of Southern England, just outside of Norwich, lies a hugely impressive modern building completed in 1978 by the architect Norman Foster. The Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts is filled with some of the greatest works of contemporary art: here we find masterpieces by Henry Moore, Giacometti and Francis Bacon.

The collection is made possible thanks to the enormous wealth of the Sainsbury family, which owns and runs Britain’s second largest supermarket chain that bears its name. Discounted shoulders of lamb, white bread and special 3 for 2 offers on tangerines have led to exquisite display cases containing Giacometti’s elongated, haunting figures.

The gallery seems guided by values that are light years from any actual supermarket. It is feeding your soul, the curators are deeply ambitious about the emotional and educational benefit of the experience: they want you to come out slightly improved. A visit is a special occasion (though they hope you’ll come often).

From a very different direction, the Sainsbury family arrive at a strikingly similar conclusion to Xu Zhen. Art and supermarkets are essentially opposed. And like Xu Zhen, the Sainsbury’s are caught in an identity trap, though a very different one: that of the philanthropist. The philanthropist is imagined as someone who makes a lot of money in the brutish world of commerce and then makes a clean break. They devote their wealth to projects that are studiedly non-commercial. The philanthropist fears that if they ever took an art-loving attitude to their businesses they would suffer economic collapse. Instead of making big things happen in the real world, they would become mere artists who make little interesting things that live only in the sheltered, subsidised world of the gallery.

It’s a strangely tantalising situation. The artist finds something loveable and much that’s wrong around supermarkets, but can’t imagine running one and bring the ideals of art into action in that arena. The supermarket owners love art, but can’t imagine bringing their art-loving side into focus in their business. They are both like pioneers, at the edges of unexplored territory. There is a huge idea they are both circling round. The goal is a synthesis of business and art: a supermarket that was truly guided by the ideals of art, capitalism that is compatible with higher values.

A supermarket governed by the values of art would not be selling art. It would be a genuine supermarket continuing to sell all the things we use everyday; it would still be focused on the idea that you can go round with a huge trolley and stock up on pretty much everything you require for the coming week. But it would be paying attention to the things that the arts have traditionally valued highly: sincerity, a focus on higher (as well as lower) needs, sympathy for the weak and the poor, a focus on quality and authenticity. The arts have a deeply impressive record of getting people to like things which, initially, didn’t seem at all attractive at first. At their best, they normalise and glamorise what is good. Supermarkets have a great (but currently misused) ability to make these moves. They have normalised lychees and glamorised cold-pressed olive oil. They could do the same for the idea of a just price: items which are slightly more expensive than their rivals because they have been produced under better conditions for all concerned. Or the idea of quality over quantity: one buys a smaller but better portion of cheese, a smaller but better chicken, fewer but better cherries…

At the moment, stacking shelves in a supermarket is one of the less sought after jobs:

By contrast, many people are keen to work in art and in galleries. Some will work for almost nothing, but they are willing because they are proud of their involvement: at parties they feel excited to say that they are working at a gallery even if mainly they are sweeping the store room, keeping the mailing list up to date or perching on a ladder.

These feel like opposite ends of the spectrum. But all that divides them is the idea of what the work means: we think of apples and soup cans as banal and art as special. The true irony is that works of art are often themselves homages to humble things. Cézanne thought apples were deeply wonderful, which was why he painted them. We get closer to Cézanne not so much by looking at the painting, but by looking at what he looked at – real apples on a simple table – with his appreciative eye. A Warhol soup can isn’t saying soup cans are pitiful but art is wonderful. Its meaning is really the reverse. Art is doing its job when it gets us to love the dignity of ordinary life – and business is succeeding when it provides the conditions for humane and purpose-driven work. A supermarket run under the values of art would be a glamorous, prestigious place to work: people would feel a quiet surge of pride when they mentioned they worked there.

Conclusion

Up to now, we have collectively learned to admire the values of the arts (which can be summed up as a devotion to truth, beauty and goodness, expressed via material things) in the special arena of galleries. But their more important application is in the general, daily fabric of our lives – the area that’s currently dominated by an often depleted vision of commerce. It’s a tragic polarisation: we encounter the values we need, but only in a rarefied setting while we regard these values as alien to the circumstances where we most need to meet them.

We want to simultaneously raise the ambition of artists: to make their ideals powerful in our lives – and of business: to serve us better. The two ambitions are ultimately very closely related.

The supermarket is one example in the wider class of commercial projects that should, ideally, be run according to the values of art, which could include: financial services, property development or home insurance. These corporations could use the ambitions and ideas that at the moment circle around art to better serve the needs of their customers.

In part, what we need to do is get artists out of an ironic mode and equip them with the right skills. We need artists who are good at dealing with employment contracts and balance sheets; who are excited by organisational flow charts and are undaunted by shareholder meetings. At the same time, we need to raise the ambitions of business people, stop them spending their surplus on art, and instead encourage them to invest (for surplus wealth buys you time to make good ideas stick) in making their core activities themselves more in line with the spirit of art. We should be seeking to make money via the values of art, rather making it in disregard for those values, and then funding a museum. That is the challenge for the future.