Self-Knowledge • Behaviours

On Taking Drugs

It’s easy to have a pretty negative view of drugs: the news is always going on about police raids on drug dealers, kids tripping dangerously at raves, overdoses and rehab.

It goes without saying: things can go horrifically wrong around drugs. But our intense awareness of the negatives is in danger of creating a misleadingly narrow view of the subject. Drugs are – at best – serious, dignified, noble and important, and we need more of them in our lives.

The real issue is: we don’t have a correct sense of what a drug is – and what the drugs might be that we truly stand in need of.

Essentially a drug is a thing, anything, that alters your mood, acting via either the body or the senses to make an impact upon the mind.

We’ve come to associate the impact of drugs with the heightening of a particular band of emotional states: the weird, the escapist, the hyperactive and the ecstatically relaxed.

But in truth, there are far more interesting, fruitful and positive directions in which we should want our minds to be altered. We’re only at the start of understanding the possibility of drugs.

The task of a drug is simply to alter mood in any positive direction in sympathy with one’s highest ambitions. So we need drugs to help us be more self-analytical, more hopeful, less prone to irritability, more politically tolerant and better at listening to other people, especially partners, when they have legitimate complaints against us.

Fortunately, there are a lot more things that are drugs than we ordinarily suppose. We need to move away from the idea of drugs as pills that someone gives you at a party when you’re 16, that will make you feel high, sick, possibly kill you – and make you look cool and shock your parents.

The word ‘drug’ happens to be sitting on a crucially important and large idea: the generation of benign and positive states of mind through the use of external physical resources. Any properly accurate list of drugs we have available should include the following:

Pomegranate Juice

Coffee stimulates, but in the right dosage, just-squeezed orange-juice (with a touch of lemon) briefly strengthens the will – and makes us more able to face tricky tasks. The much less well known pomegranate juice has a soothing, calming effect which helps one be less prickly around perceived insults and slights.

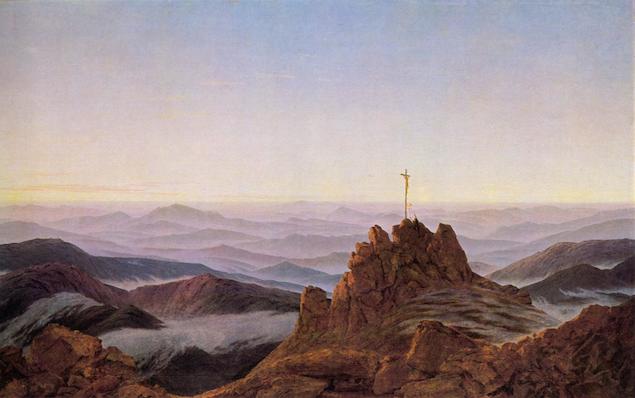

The Paintings of Caspar David Friedrich

This physical object, titled Morning in the Riesengebirge by the German 19th-century Romantic artist Caspar David Friedrich, is a drug that hangs on a wall and is intended to produce an expanded state of consciousness in which the pain of immediate troubles is lessened by a euphoric recognition of the immensity of nature.

Emmental Cheese

It’s mild, savoury taste and yielding (but not crumbly) texture quickly bring on a feeling of repleteness. Emmental is a quick anxiety reducer. Like chocolate and hot buttered toast, Emmental cheese is an envy-suppressing drug.

Mozart’s Aria: Soave sia il vento

This musical drug briefly induces a heightened state of tenderness towards strangers and a mood of generosity towards one’s own and others’ stupidity when it comes to relationships.

The precise effects of these substances will vary from one person to the next – so a key task with these and all drugs is to get good at working out what we really need to optimise our own functioning. What might be a crucial corrective for one person could be deeply unhelpful for another. In wiser societies than ours, we would have drug advisers who could do a full audit of our natures and come up with extended menus for what sort of drugs might be most suitable for our given characters. Mozart in the late evening on a transatlantic flight can prove tricky for some.

In the past, ambitious societies have looked very seriously at drugs, and organised their consumption into rituals.

A very popular drug – tea – was employed in Buddhist ceremonies in Japan from the 13th century onwards. The drug was used to promote focus, concentration and a feeling of strong connection to other human beings. You might have to sit in a particular way taking your tea drug; wait patiently to be served and consume a very specific quantity while contemplating the branch of a pine tree moving ever so slightly in a breeze outside.

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, A Dedication to Bacchus (1889)

The Ancient Greeks were also very interested in drugs. Their ritual – known as the Dionysian Mysteries – was built around the highly structured use of red wine as part of a religious festival. Participants would drink and dance in search of a sense of collective belonging, as decreed by the God Dionysus.

By making what might otherwise descend into binge drinking into a religious festival, the Greeks cleverly directed the immense power of alcohol towards the most beneficial states of mind. Instead of being a reason for getting into an argument with one’s spouse, or messing up a wedding speech, wine became an occasion for fostering trust and loyalty between citizens in the city.

Our moods play an immense role in our lives and yet we tend to be haphazard in the way we identify and deal with them. At present, we play around with moods with hugely clumsy and dangerous instruments – with drugs that we hardly understand and that can have a devastating impact on our well-being.

We need to broaden our sense of what a drug is, allow Mozart and Emmental cheese into the mix, and then have a system that intelligently administers the drugs we need to flourish. We’re still at the dawn of learning how to take drugs properly: we’re likely to be far cleverer drug takers in the future.