Leisure • Literature

Gustave Flaubert

Gustave Flaubert was a great French 19th-century (1821-1880) novelist who deserves our love and sympathy; as much for what he wrote as who he was.

We can admire him for four reasons at least:

HE UNDERSTOOD THE PURPOSE OF TRAGEDY

Flaubert produced arguably the single greatest tragic novel ever written: Madame Bovary – which he worked on for five years and published in 1857.

The point of a tragedy is to allow us to experience a degree of understanding for others’ failure so much greater than what we ordinarily feel. It shakes us from our customary moralism and brittle superiority. It helps us empathise in the way the modern media usually prevents.

In the summer of 1848, a terse item appeared in many newspapers across Normandy. A twenty-seven year old woman named Delphine Delamare living in Ry just outside Rouen, had become dissatisfied with the routines of married life, had run up huge debts on superfluous clothes and household goods and had committed suicide under emotional and financial pressure. Madame Delamare was leaving behind a young daughter and a distraught husband.

One of those reading the newspaper was a twenty-seven year old aspiring novelist, Gustave Flaubert – who grew so fascinated by the story, he used it to provide him with the exact plot structure for his eventual novel.

One of things that happened when Madame Delamare, the adulteress from Ry, turned into Madame Bovary, the adulteress from fictional Yonville, was that her life ceased to bear the dimensions of a black-and-white morality tale.

Readers saw how easy it is to have a thoroughly miserable marriage without being in any way a bad person. Flaubert’s novel shows us the tensions and travails of married life without taking sides.

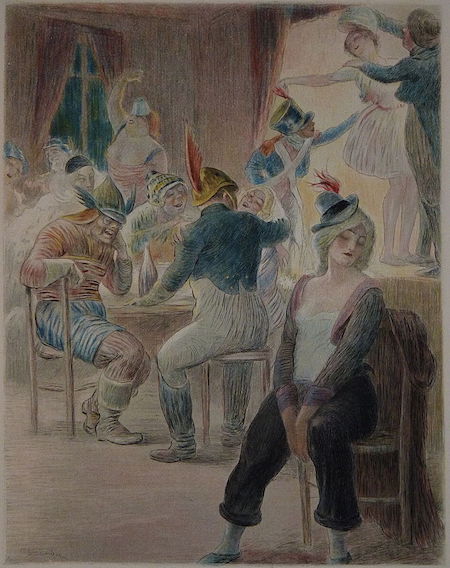

Emma gets bored with her husband, loses interests in her child, runs up debts, has affairs – and eventually kills herself. But by the time readers had taken in how she had pushed arsenic into her mouth and been laid down in her bedroom to await her death, they would not be in a mood to judge. All they could feel was pity at the cruelty and senselessness of life.

Flaubert seemed almost deliberately to enjoy unsettling the desire to find easy answers. No sooner had he presented Emma in a positive light, than he would undercut her with an ironic remark. But then, as readers were losing patience with her, he would draw them back to her, would tell them something about her sensitivity that would bring tears to the eyes.

We end Flaubert’s novel with fear and sadness at how we have been made to live before we begin to know how, at how limited our understanding of ourselves and others is, at how great and catastrophic are the consequences of our actions and at how pitiless and vengeful the upstanding members of the community can be in response to our errors.

Tragedy inspires us to abandon ordinary life’s simplified, judgemental perspective on failure and defeat; rendering us generous towards the foolishness and errors that are endemic to our nature.

WHAT WE READ MATTERS

A particular aspect of Madame Bovary’s tragic end sticks out: Flaubert tells us in no uncertain terms that the reason Emma Bovary grew so dissatisfied, unfairly so, with marriage – and therefore embarked on her disastrous affairs – was because of the books she had read.

He tells us that from a young age, Emma used to read Romantic novels that gave her an unrealistic, overly rosy picture of love that left her unprepared for the reality of marriage.

Emma was unprepared for how boring it can be to have dinner with the same person every night and by how difficult it is to keep a relationship alive after one has a baby – and therefore responded with too great a degree of panic, having multiple affairs to remind herself that she was still capable of passion and going shopping for more than she could afford as an alternative to the sometimes tedious business of bringing up a child.

What might ultimately have saved Emma Bovary was to read the novel of which she is the heroine. It’s a novel about love designed to cure us of the naive illusions about love created by bad novels.

THE STUPIDITY OF MODERN MEDIA

Flaubert couldn’t stand newspapers. He belonged to a generation that had experienced the rise of mass-circulation newspapers at first hand and believed that these were spreading a new kind of stupidity – which he termed ‘la bêtise’ (idiocy) – into every corner of France.

Idiocy wasn’t the same as ignorance for Flaubert, because it was compatible with knowing a lot of things – it just meant understanding nothing.

The most loathsome character in Madame Bovary, the pharmacist Homais, is introduced early on as an avid consumer of news who sets aside a special hour every day to study ‘le journal’ (Flaubert keeps the word in italics throughout, to send up the neo-religious reverence in which this object is held).

In the 1870s, Flaubert began keeping a record of what he judged to be the most idiotic patterns of thought promoted by the modern world in general and by the newspapers in particular. Published posthumously as The Dictionary of Received Ideas, this collection of clichés, organised by topic, was described by its author as an encyclopédie de la bêtise humaine (an encyclopedia of human stupidity). Here is a random sampling of its entries:

BUDGET: Never balanced.

CATHOLICISM: Has had a very good influence on art.

CHRISTIANITY: Freed the slaves.

CRUSADES: Benefitted Venetian trade.

DIAMONDS: To think that they’re nothing but coal; if we came across one in its natural state, we wouldn’t even bother to pick it up off the ground!

EXERCISE: Prevents all illnesses. To be recommended at all times.

PHOTOGRAPHY: Will make painting obsolete.

It is worth noting how many of the Dictionary’s clichés touch on sophisticated disciplines such as theology, science and politics, without, however, going anywhere very clever with them

The modern idiot could routinely know what only geniuses had known in the past, and yet he was still an idiot – a depressing combination of traits that previous ages had never had to worry about. The news had, for Flaubert, armed stupidity and given authority to fools.

A HATRED OF THE FRENCH BOURGEOISIE

Flaubert was a bourgeois, a middle class Frenchman, and yet he loathed a great deal to do with his country and class.

For Flaubert, the French bourgeoisie could be a repository of the most extreme prudery, snobbery, smugness, racism and pomposity.

‘It’s strange how the most banal utterances [of the bourgeoisie] sometimes make me marvel,’ he once complained in stifled rage, ‘There are gestures, sounds of people’s voices, that I cannot get over, silly remarks that almost give me vertigo…the bourgeois…is for me something unfathomable.’

He wrote that he had nothing but disdain for this ‘good civilisation’ that prided itself on having produced ‘railways, poisons, cream tarts, royalty and the guillotine.’

What Flaubert hated above all was pomposity. This quote to his girlfriend Louise Colet, written in 1846, gives us an insight: ‘What stops me from taking myself seriously, even though I’m essentially a serious person, is that I find myself extremely ridiculous, not the kind of small-scale ridiculousness of slapstick comedy, but rather a ridiculousness that seems intrinsic to human life and manifests itself in the simplest actions and most ordinary gestures. For example, I can never shave without starting to laugh, it seems so idiotic. All this is very difficult to explain…’

He was in the end a global citizen: ‘I’m no more modern than Ancient, no more French than Chinese, and the idea of a native country, that is to say, the imperative to live on one bit of ground marked red or blue on the map and to hate the other bits in green or black has always seemed to me narrow-minded, blinkered and profoundly stupid. I am a soul brother to everything that lives, to the giraffe and to the crocodile as much as to man.’

In his Dictionary of Received Ideas, there was an entry on: FRENCH – ‘How proud one is to be French when one looks at the Colonne Vendôme’.

Paradoxically, one can be proudest to be French when one reads Flaubert, for aside from hating a lot about his country, he also captures some of its best and wisest sides.

We should read him for his earthiness, his humanity, his frankness and above all else his generosity of spirit.

At the age of 17, Flaubert wrote, in a melodramatic mood, ‘Art is superior to everything, a book of poetry is worth more than a railway.’

It rarely is; but it might almost be worth giving up a railway line or two for the sake of Flaubert’s works.