Self-Knowledge • Emotional Skills

How to Decide

Introduction

A good life is the fruit of a succession of good decisions, especially around love and work. However, we seldom accord the business of decision-making the kind of careful attention it requires. When faced with a large decision, we lack rituals and procedures. We typically procrastinate, lean on the nearest person or rush headlong into an unexamined solution. Fortunately, decision-making is a skill and – like any other – it can be taught. The chief enemy of good decisions is a lack of sufficient perspectives on a problem. We should systematically think through any issue from six distinct angles: through the eyes of – variously – our Enemy, our Gut, Death, Caution, Courage and our Parents. As we try out, juggle with and then synthesise these oblique perspectives, we will feel our sense of possibility expand – and a tolerable way forward gradually emerge from the present confusion.

Enemy

Our enemies have deep insights into us: they know our frailties, they actively want the worst for us and they’re bringing a desperate, mean intelligence to bear on our case. Thinking of them helps beautifully to clarify our thoughts. It can be unfeasibly hard to be a true friend to ourselves, in the way we should be; our minds may well go blank if asked to imagine what a sweet and well-meaning person might advise us to do next. We’re so much better at getting into the heads of our bitterest foes. They appreciate our weaknesses and temptations like no other. We can at last put these characters to constructive use: by doing the very opposite of what we suspect (probably very correctly) they might propose and say. We will be energised and focused by the haunting voices of those dispiriting but very telling and mesmerising judges: those who refuse to believe in us.

Gut

In a sense, we know the answer already – or at least one version of it. We call it gut-instinct and it is there from the moment a dilemma first appears. The Gut is the accumulation of all the decision-making lessons we’ve ever derived across our lives, revealed unconsciously at speed. Most of us have become rather good at not listening to the Gut. Probably it got us into trouble a number of times, maybe pushing us into some crazy moments for which we paid dear. Now we pride ourselves on being thinking people, who take their time, gather evidence and make full use of their higher mental powers, as well we should. Nevertheless, we thereby lose a source of important insight. We should be brave enough to invite our Gut to the decision-making table, not necessarily in order to follow it but in order to know what it wants, and then submit its stubborn and impatient certainties to gentle rational cross-examination.

Death

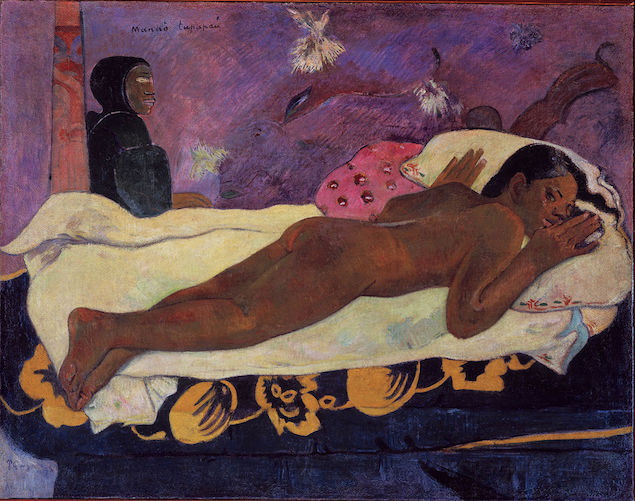

The largest, but always easily-forgotten certainty, is that all our decisions are unfolding in the backdrop of a giant ticking death clock. We should listen to its beat and take its daunting messages to heart. The thought of Death has a habit of highlighting our responsibilities to ourselves and of weakening our concern for living according to what is expected of us by society. It is a terrifying agent of authenticity. Death may lend us a perverse new sort of confidence to tackle challenges. By frightening us about one enormous thing, it may make us less scared of the many smaller obstacles in our way. Our lives won’t be what they could be unless we submit pretty much every choice we face to the arbiter of eternity and oblivion. The thought of death is the guarantor of the meaningfulness of our lives.

Caution

Somewhere around the table at every decision must be the voice of caution. It wears dowdy clothes and speaks quietly. It certainly lacks glamour in an age of bravado and bombast. It’s easy to feel that we must always and invariably jump – because life has to be about giving the new a go. It may not be. Let’s remember, Caution clears its throat to tell us, that most new businesses fail, most schemes end in disaster and most relationships merely rehash the themes of the current unsatisfactory one. Furthermore, there is a huge amount to be lost and there are many people around us who may get very hurt by our ambitions. The devil one knows may just have the edge over the many demons one doesn’t quite. Caution does not look down on the idea of compromise, it recognises that there are, at points, simply no ideal options for the imperfect beings we ultimately are. Caution has the bravery not always to rebel against reality.

Courage

From an early age, we’ve learnt how to follow the rules, wait in line and do the dutiful, expected things. We can be good boys and girls; it got us to where we are today. There would have been no other way to learn how to spell, drive a car or take up a position in the working world. But there can now be a subtle risk from an opposite direction; the risk of being overly faithful for too long to conventions that were dreamt up without our particular interests and hopes in mind. At points, we need vigorously to relearn the art of Courage, to remember that the happiest lives have invariably had inflection points where people did the slightly unexpected and weird thing, took a gamble and won. Sometimes, Caution is just weakness and cowardice wrapped up in the cloak of self-deception. Courage and Caution need to fight this one out, without any presumption of victory on either side.

Parents

They have been in our heads longer than anyone else. They don’t necessarily know best, that is more than evident. But we have to bring their way of thinking to consciousness, because it is there anyway, constantly subtly influencing what we think and may plan. We should articulate directly what each parent (if we knew them) would have advised us to do. Even if they are long dead, the exercise won’t be hard. We are probably their best mimics and interpreters. Then comes the job of sifting through the advice. A lot of it stands to be self-serving. They may (oddly) have been a bit competitive with us. They may have made mistakes they needed to justify to themselves; they may not have wanted us to be happy in our own way. But they also – at their kindest moments – genuinely didn’t want us to suffer more than we had to or repeat the mistakes they had already paid dearly for. At moments of great choice, we should bear to reclaim our real inheritance: the experience of those who came before us.