Leisure • Western Philosophy

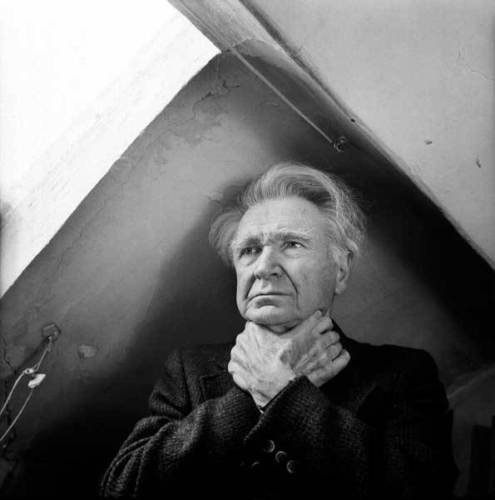

E. M. Cioran

Towards the end of the twentieth century, a celebrated Romanian-French philosopher and aphorist was invited to speak in Zurich. He was introduced with rhetorical pomp and flattering comparisons to the likes of Kierkegaard and Schopenhauer. The speaker smiled, and immediately confounded his German interpreter by beginning his presentation with the words: ‘Mais je ne suis qu’un déconneur’ / ‘But I’m just a joker’.

A few of his critics might agree, but they would be wrong. For Emil Mihai Cioran is very much worthy of inclusion in the line of the great French and European moral philosophers and writers of maxims stretching back to Montaigne, Chamfort, Pascal and La Rochefoucauld.

Cioran was born in Rasinari, Romania, in April 1911. His father was a Greek Orthodox priest. Both facts were to be key in his later work. The writer’s Romanian origins are often taken as the source of a brooding, Romantic, fatalistic temperament while his father’s ecclesiastical calling finds echoes in his son’s unswerving preoccupation with themes of religion, sainthood and the dangers and joys of atheism.

From 1920 to 1927, Cioran studied at the lycée in Sibiu, in the outer reaches of Transylvania.

In 1934, at the age of only 23, he published his first book in Romanian, On the Heights of Despair. The book contains in embryo much of the lucidly bleak, nihilistic thinking that he’d develop throughout his life. He explained that writing had been an alternative to shooting himself.

This is an author to read at moments of despair and melancholy. He doesn’t depress us, merely makes us feel less alone with our sorrows.

Here is a peak inside his work:

‘It is not worth the bother of killing yourself, since you always kill yourself too late.’

‘Only optimists commit suicide, optimists who no longer succeed at being optimists. The others, having no reason to live, why would they have any to die?’

‘Write books only if you are going to say in them the things you would never dare confide to anyone.’

And:

‘What do you do from morning to night?’

‘I endure myself.’

1937 proved a pivotal year for Cioran. He moved to Paris and soon became a French citizen. He never returned to the country of his birth. It was a move that provided him with another reason to be sad: exile. And yet he asserted that anyone who doesn’t feel themselves to be an exile has no imagination. ‘Only the village idiot thinks they belong,’ he noted.

Cioran sat out the Second World War in Paris. In its aftermath, he approached the famous publishing house, Gallimard, with his first work in French, A Short History of Decay, published in 1949. Writing in French was he said, ‘like writing a love letter with a dictionary’.

The book became a bestseller, the first in a series of devastatingly wicked and dark texts composed mainly of aphorisms and tart short essays. Each title comes as a provocation or a punch: Syllogisms of Bitterness, The Temptation to Exist and his masterpiece: The Trouble with Being Born.

Each book deals relentlessly with themes of illness, death and suicide. It was a rather touching irony that the author lived to the ripe old age of 84. By the time Cioran died in 1995, he had become a cult in France, attracting the sort of faddish attention he witheringly denounced in his work. Every life, he maintained, is utterly peculiar – and wholly unimportant.

In the age of Walt Disney, this kind of darkness matters.

Cioran’s writing belongs in the line of those great aloof European miserabilists, including La Rochefoucauld, Chamfort, Leopardi, Nietzsche and Beckett. Like them, he saw civilization as an absurd distraction from the ultimate meaninglessness of existence.

‘Only an idiot could think there is a point to any of this,’ he insisted.

But he always kept his wit and good cheer.

One of his greatest sources of sorrow was that he couldn’t sleep very well – and was often up at 3am. He’d walk around the streets of Paris until dawn. He noted sardonically in The Trouble with Being Born, ‘What is that one crucifixion compared to the daily kind any insomniac suffers?’

Cioran was obsessed by suicide. But better to live, he wrote, and yet think and act as though one were already dead. After all, he said: why deprive oneself of the consoling idea of no longer being around?

‘Continuing to Live is possible only because of the deficiencies of our imagination and our memories.’ he wrote.

‘I’m simply an accident. Why take it all so seriously?’

But suicide was a constant relief as an idea:

‘We dread the future only when we are not sure we can kill ourselves when we want to.’

‘Having always lived in fear of being surprised by the worst, I have tried in every circumstance to get a head start, flinging myself into misfortune long before it occurred.’

Our age is notably optimistic and it makes us suffer hugely from being so. We are all, in private, a lot sadder than we are allowed to admit.

Writers like Cioran provide an occasion for the sadness inside all of us to be communally expressed and thereby a little, but only a little, diminished and softened.

In his beautiful book, The Trouble with Being Born, Cioran wrote:

‘I can be friends with people only when they are at their lowest point and have neither the desire nor the strength to restore their habitual sentimental illusions.’

It’s precisely in that kind of mood – into which all thoughtful people must sink on a fairly regular basis – that we can be blessed to find the dark and consoling works of Cioran waiting for us.