Self-Knowledge • Melancholy

Parties and Melancholy

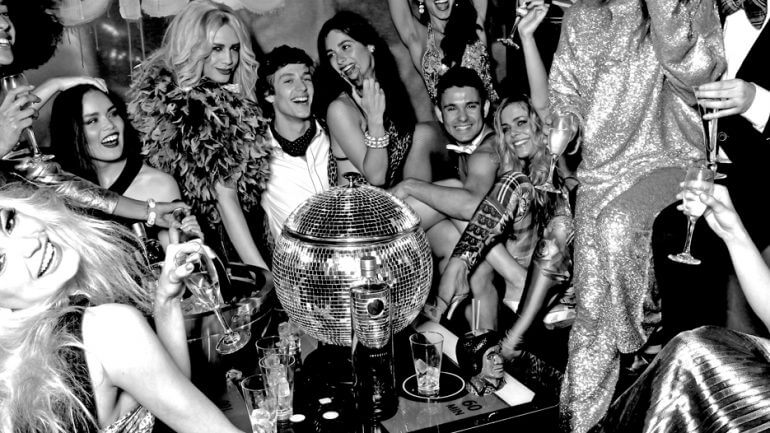

The great problem with parties is their implicit understanding of loneliness. From the moment we arrive at most of them, we’ll notice that intense efforts have been made to generate a welcoming and sociable atmosphere. Someone will have rigged up a sound system, there might be balloons bouncing around the ceiling, drinks may be brightly coloured. More significantly, some extremely well meaning people will be keen for us to have a good time. As the evening unfolds, they might cheerfully come up to us and ask: Are you well? Are you having fun?

The intentions are moving; the results more complicated. There is broad agreement that the purpose of a party is to allow individuals to come together in order to forget their painfully isolated destinies and revel for a time in an experience of shared humanity. That’s what the loud bass, the alcohol and the bonhomie are there to help us with. The difficulty lies in the underlying analysis of what might truly help people to shed their customary alienation.

The vast majority of parties proceed with the view that it is displays of happiness, especially exuberant happiness, that are what help people to relax and feel content. It is seeing another’s good mood, hearing their stories of success and their joyful description of forward momentum, that will help us to tap into our own sources of delight and confidence.

It sounds logical except that the truth of our psychology is stranger: what really breaks us out of our isolation is not to see others cheering, but to witness that the troubles that beset us – the shame, guilt, regret, despair, irritation and self-disgust – are not merely personal curses, as we had suspected in the echo-chambers of our fearful minds, but have counterparts in our fellow humans. It is the sorrows of others that confirm us in our gloom and help to raise our spirits.

It is our collective misfortune that society tends to present us with such an edited picture of what a normal human being might be like, drained of so much of the trouble and sadness that truly afflict us all. Without this necessarily being anyone’s intention, we are left to feel freakish – when we are in fact profoundly normal but have been measuring ourselves against an impoverished public account of reality.

A good friend should allow us to glimpse a broader, more accepting vision of existence; they should permit us to see that we can have low moods, moments of serious self-hatred and ambivalent feelings about our careers or families – because everyone else does as well. These aren’t signs of degeneracy or sin, just evidence that life is proceeding more or less according to plan. Telling a stranger how well we’re doing might buy us their awe, only the revelation of a problem will turn them into a friend.

With a new psychology of companionship in mind, we can start to imagine what a truly sociable party might look like. There might not be any loud upbeat music, perhaps just a sorrowful Bach cello concerto or a Requiem Mass somewhere in the background. The host would invite us to share everything about our lives that was less than perfect and that society had censored in the world beyond. Here, surrounded by kindly faces, we would have the chance to reveal how dark some of our thoughts had been – and the extent of our lamentations and losses. Heading home after such an evening, we would be sincerely happy because we had finally been able to offload, and hear from others, how much of life is sadness.

It is easy to feel that one must be a misanthrope for hating parties. But the opposite may in reality be true. We hate parties because we are unusually and intensely keen for human connection; which we simply can’t find at the level of depth we crave at the average gathering. We want to be alone not because we genuinely don’t like company but because we like the real thing so much, and because the simulacrum of company on offer reminds us too powerfully of an isolation that breaks our hearts.

We are generally left standing at parties surrounded by forty people, feeling more isolated than we would at home or the surface of Mercury, because the forty, who could have offered each other so much, are collectively trapped in an ideology of false jubilance. In a utopian future, we will have learnt how to throw those paradoxical-sounding occasions, melancholy parties. There will be no more jolliness and bragging on display. There will only be some unusually vulnerable and candid people sitting around, confessing how hard they find it to be human and very glad to have found a bunch of like-minded souls who are having just as much trouble as they are. That would be something to celebrate.