Sociability • Social Virtues

Kindness Isn’t Weakness

Some of what holds people back from showing greater love is a sense that it would be dangerous and woolly-minded to do so. Too much sensitivity and sweetness, too much tolerance and sympathy appear to be the enemies of an appropriately grown-up and hard-headed existence. Such types are not saying that it wouldn’t be delightful if we could display compassion and tenderness towards one another, if we could be sensitive to the sufferings of strangers and quick to forgive and understand the failings of our colleagues and lovers; they just don’t think that this has much relevance in the real world.

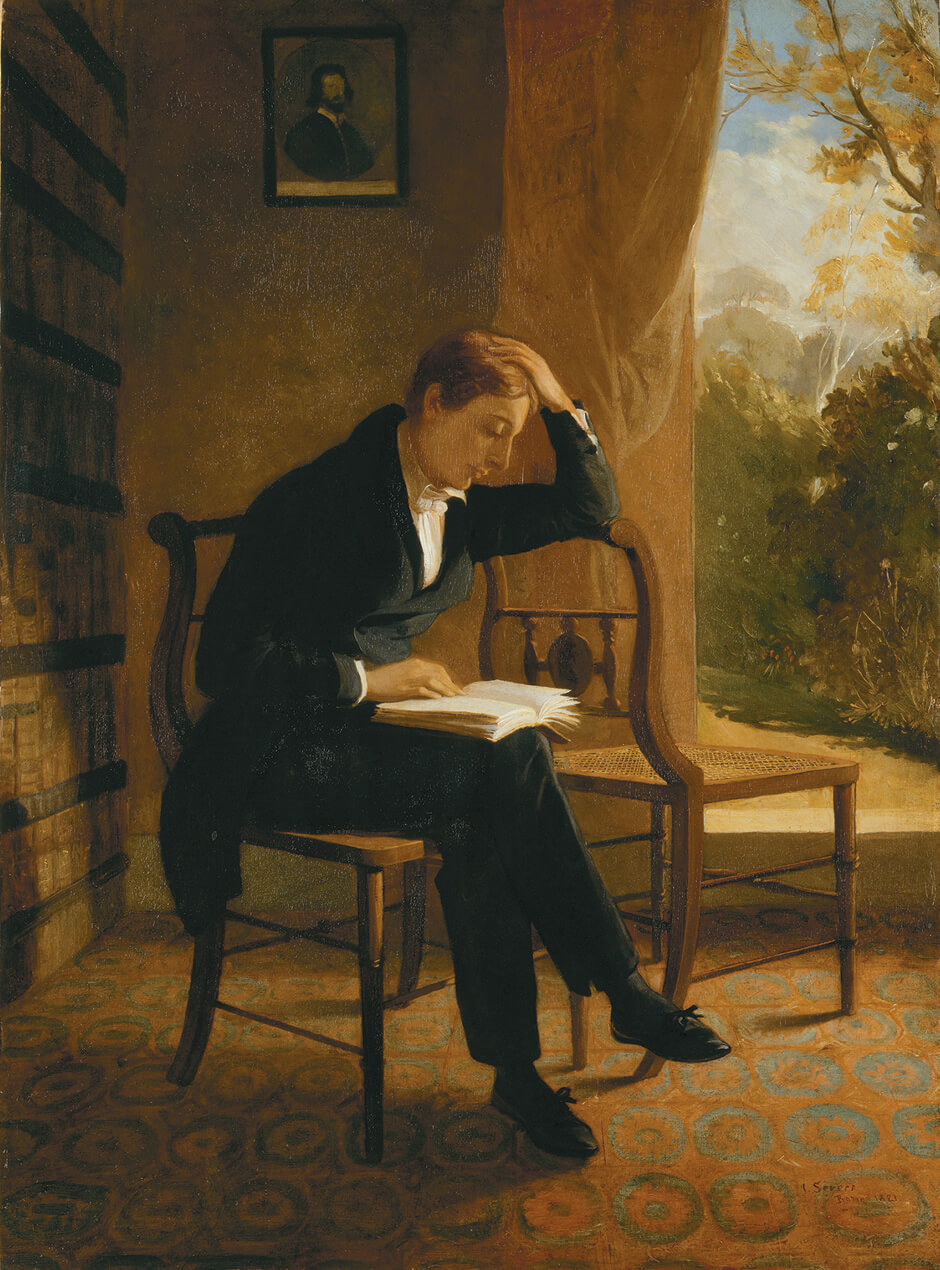

In seeking to show why, they might refer to cases like that of the early-19th-century English poet John Keats, a gifted young man who wrote movingly about birds, the sky and autumn mists and stands as a representative of a universal attitude of gentleness and kindness, an exemplar of sensitivity and love.

Keats’ life was far from an inspiration, however; indeed, it was a practical disaster. He trained as a doctor, but never got a job; he received a modest inheritance on his mother’s early death, but never managed to earn any money and was constantly pursued by creditors. His poems were not very well received; one particularly practical-minded reviewer described him as ‘a miserable creature’, longing for ‘a world of treacle’, in which everyone and everything is sweet. He died of tuberculosis aged twenty-five.

There seemed to have been a fatal misalignment in his life: Keats was broadly and warmly loving, but success eluded him. His ideas may have sounded elevated, but they didn’t help him to secure health or peace of mind. If we are to thrive, the interpretation goes, we need to harden ourselves, be realistic and accept the painful but important fact that excesses of sensitivity and kindness actively ruin our chances of flourishing.

Yet the temptation here is to assume that being loving and being realistic are contraries, that they are set like a fork in the road. We can be practical or we can be loving, but never both. The dispute is commonly translated in political terms; broadly, one side wants to be kind but will probably destroy the economy, the other side wants to support material prosperity, but the means will be brutal.

What has too often been missing in our ideas is the possibility that we might hold on to both love and rigour. Rather than seeing practicality and sympathy as alternatives, we could see them as different ingredients within a life. We’re not being asked to choose; good results must depend on a combination.

An exclusively loving person might be inclined to overlook how much love needs a clear eye for unwelcome facts. It’s not loving to tell someone that their business idea is bound to succeed when it is in fact naive or unworkable. It’s not loving to persuade someone that they are delightful just as they are when they may benefit from acquiring further skills or education. Love that loses touch with the reality of an imperfect world is no longer kind.

Yet the pure pragmatist, who trusts that cynicism lends them a perfect grip on how things work, is equally deluded. Kindness and generosity are essential lubricants; to get the best out of people involves magnanimity and decency; in order to negotiate successfully we need to feel the legitimacy of another person’s concerns. If we are to persuade others of anything, we have to enter into their minds with solicitude.

We’re lacking vivid descriptions and portrayals of people who have learned to be practical and loving. There have been too many people like Keats on the one hand and too many robber barons on the other. Sanity involves recognising that it is as naive and ultimately as dangerous to surrender indiscriminately to the claims of love as it is to ignore them altogether.