Why We Shouldn’t Fear Asylums

For many of us, a fundamental priority is that we should never, ever end up in a psychiatric hospital — what used to be called an asylum (or, as some might put it pejoratively, a madhouse or loony bin). We are – for understandable reasons – deeply wedded to the idea of our sanity.

And yet looked at more generously, ‘sanity’ is not an unassailable island with rigid or impregnable boundaries: it is a continent that is constantly suffused with waves of trouble, pain and confusion. A degree of mental perturbance belongs to health. A share of madness is, and should be, present in every good and sane life.

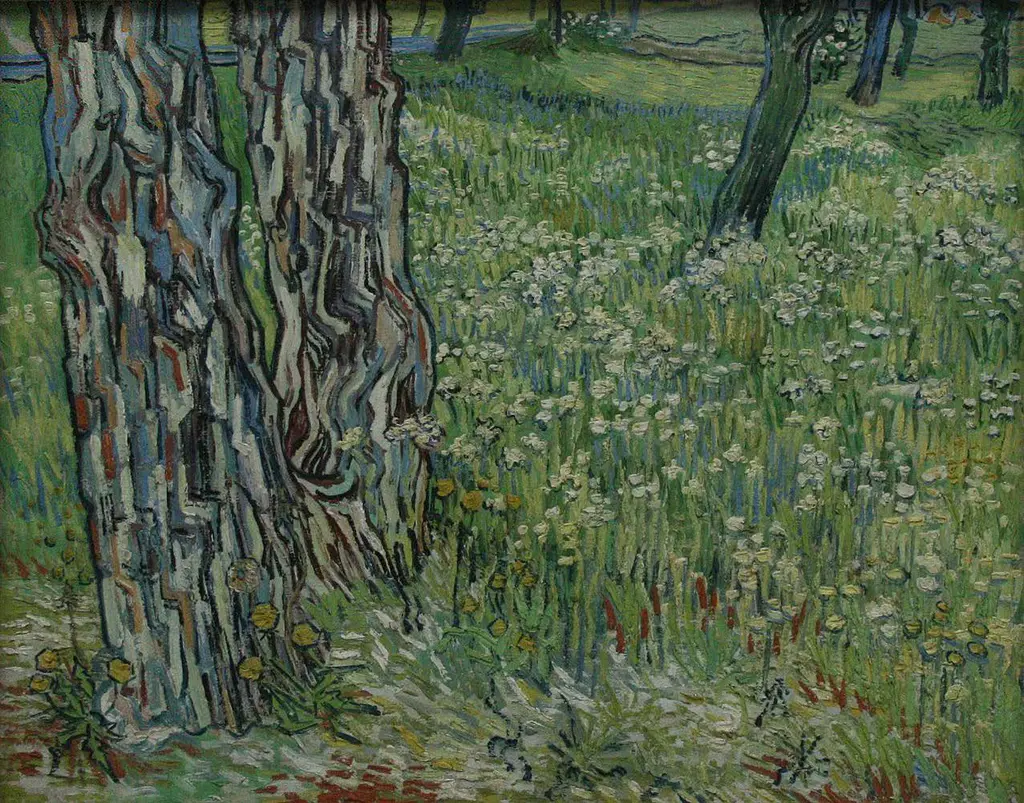

Vincent Van Gogh entered the Saint- Paul Asylum in Provence in May 1889 and was to remain there until May the following year. He had grown increasingly exhausted in the previous months, his mood veering between exultation and despair, visionary fervour and dejected self-loathing. At first, he spent a lot of time in bed – sleeping, thinking and writing to his brother. Then gradually he felt well enough to paint and did so both in his room and in the grounds. He particularly loved the asylum’s gardens: its pine trees, caterpillars, butterflies and flowers (bluebells, dandelions and – most famously – irises). It was here that he painted some of his best-loved works; the Van Gogh we know was reborn in this walled garden in Provence.

Nature wasn’t just a pretty spectacle, it was evidence of the human capacity to endure and overcome appalling degrees of loss and shame. This was a man who had thought very seriously of killing himself only months before; in nature, he found a stream of counterarguments. His tree trunks were weathered and experienced, they had known storms and years of buffeting and damage by the wind, but they were hardy and determined. Growing around them, his dandelions appeared innocent, copious and hopeful.

Part of the reason we break is that we do not – ordinarily – allow ourselves to bend. We believe we have no option but to keep going, to put up a front and to be so-called brave. But recovery only begins the moment we accept that we cannot cope, that it has become too much and that the disturbances we have been warding off for too long have now got the better of us.

However alarming our state might be to those around us, we might almost be grateful for our collapse. A breakdown can be a prelude to a breakthrough. In the midst of our despair or mania, things may be rearranging themselves inside. We are, confusedly, expressing a longing for a new kind of life: a more caring relationship, a more authentic career path, a more compassionate acceptance of ourselves and our past.

One day, we might find ourselves in an asylum. We shouldn’t despair that this is where we have ended up. Many have been here before us – and some of them understood life better than anyone. We should feel proud of how courageous we have been in admitting that we are defeated. At last we have an opportunity to cry, to think and to heal. We don’t need to do very much; we can lie in bed for hours and when we feel up to it, at our own pace, go out for a quiet wander among the pine trees. The old way wasn’t working; this is a new start.

When the sun comes out, we might find a comfortable bench from which to contemplate a medley of flowers with the sort of mystical delight, open-hearted joy and love for life known only to those who have, in their darkest moments, been tempted to give up entirely.