Self-Knowledge • Fear & Insecurity

The Five Features of Paranoia

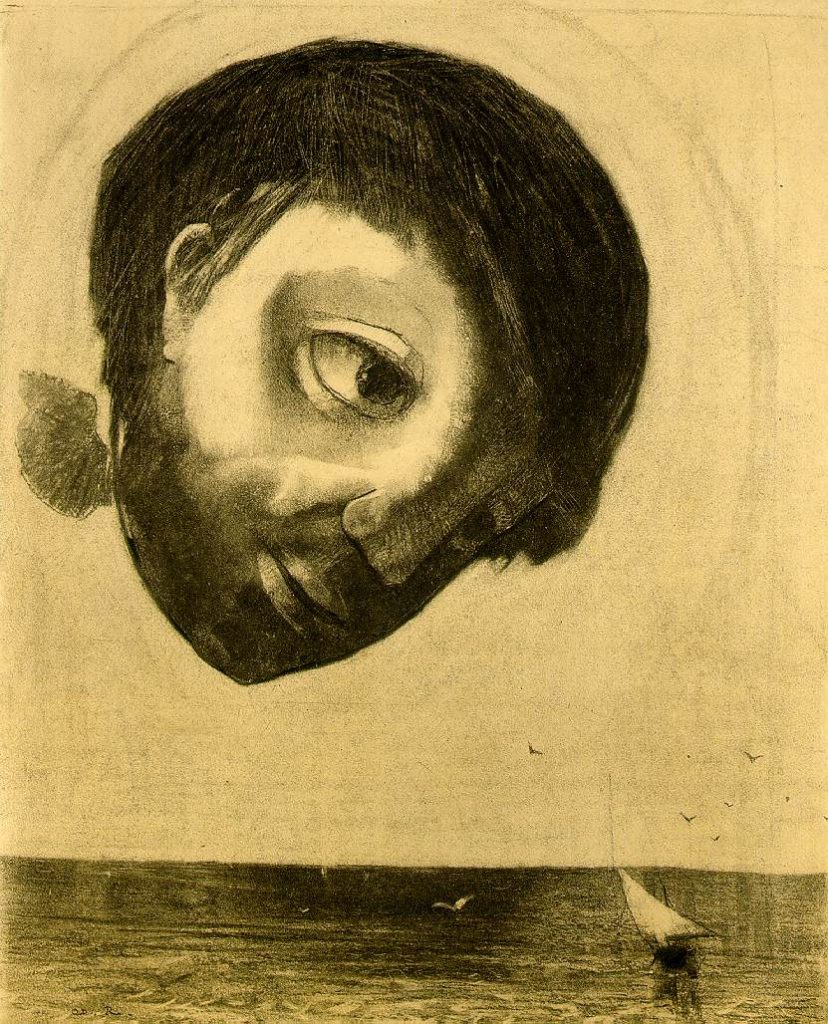

There are perhaps five main features of the very sad, indeed hellish, condition we know as paranoia…

Firstly, paranoia means we will fear a lot of people indiscriminately. Our colleagues, passers-by in the city, people on the internet, the group in the next carriage along from us, anyone close to us; all will pose a similar-size threat. A feeling of danger is widespread and constant.

Secondly, the fear is deep. The people we are afraid of will seem hugely powerful as well as profoundly malevolent. Let’s put it at its starkest: it seems ‘they’ — the angry, quietly mean and cruel ones — will want to kill us.

Thirdly, the paranoid person feels defenceless. They would love to take up arms (as it were) but they are beset by a sense of terrible weakness, as though all their bones had dissolved in the face of threat. They are wholly powerless before evil, like a deer that lays down as if dead at the approach of a lion.

Fourthly, the paranoid feel that — at some level — the attacks of others are deserved. They are extremely unpleasant but they are fitting. They suspect that they are being rightfully punished for some misdeed of whose details they are unclear but of which they believe themselves responsible.

Fifthly, the paranoid tend to feel very alone. They don’t reveal their fears to many people, or even to anyone. Theirs is a symptom bred in darkness.

The secret to unlocking the horrors of paranoia lie in making a bold intellectual leap: to be able to believe that our state of mind is primarily caused by something in the past, not the present.

If we can accept this at least in theory, we can then start to ask ourselves more searching questions, we can begin to wonder if there was ever anything way back, a concrete event or a dynamic, that remotely resembles our fears today.

— Were we ever very afraid of someone?

— How much power did they have over us?

— Did we have any ability to fight back?

— How come we feel that there may have been some justice to what we endured? Observe how we feel in some way in the wrong, or just plain wrong in and of ourselves, when we were evidently a victim.

The mind tends to be very reluctant to explore such awkward questions. Let’s remember a central fact about trauma: its victims’ deep-seated (and originally protective) inability to understand what is going on inside them. The mighty wheels of reason spin in a slush of confusion.

But there are likely, in time, to be certain recollections, especially if we allow ourselves to reflect calmly (perhaps in the bath, on a plane, on a walk or in bed under the protection of night).

— Perhaps I was very afraid of a big person long ago…

— Perhaps they belittled or humiliated me a lot…

— I could do very little, I was a tiny creature.…

— How could I have been the bad one here?

— I was so alone, who could I complain to?

Recovery depends on learning to separate out what belongs from the past from what is active in the present. The fear may tell us it is concerned with present-day threats, but we should hold on to the thought that its fuel may be coming from a long time back. Once we learn what we were once really afraid of, there will be far less to be afraid of every day.

This doesn’t mean that the present holds no dangers. That would be too idealistic. But what does threaten us now is liable to be far less dreadful than the fears that beset every moment of the paranoiac’s life.

There are enemies, certainly. But they are likely to be in a minority. There are things to be careful about. But hypervigilance is not required. Not everyone is awful. We recover by grasping that something really relatively unusual happened to us in the past — and that we were unusually powerless before it, as children are. We are drawn to the worst case because an extreme case happened to us. We are generalising from a distinctly rare and distinctly awful event.

Also, we have far more agency now than we once did. We don’t have to take too much lying down. Were we to be mishandled, we could mount an effective, steady and rational protest. We have the strength to be creative about pain. We can surround ourselves with allies. We can defend ourselves against injustice and idle rumour. We don’t have think of suicide immediately. The real awfulness is behind us; it doesn’t need to be ahead of us at every moment.