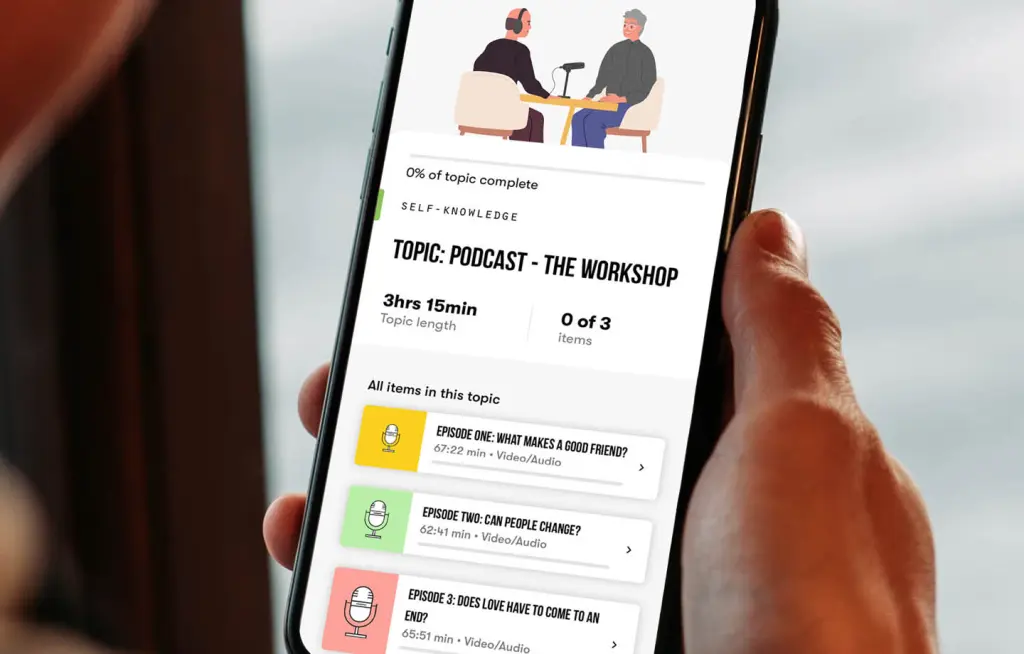

Self-Knowledge

We are devoted to bringing you self-understanding, deeper friendships, better relationships, calm, greater effectiveness at work and more fulfilment in your leisure time.

We do this via our articles, books, app, podcast, films, therapeutic services, corporate offering and new in-person experiences.

Discover books, games, and products designed to build emotional intelligence, spark meaningful conversation, and support personal growth. Explore our thoughtfully curated collection and find the perfect tools and gifts to lead a more fulfilled, reflective life.

SHOP NOW

Self-Knowledge

Self-Knowledge

Relationships

Relationships

Sociability

Relationships

A subscription to The School of Life unlocks our app – your personal centre of healing, growth and well-being – and thousands of articles online. Subscribe now for a full year of self-knowledge.

START MY FREE WEEK

Whether you’re going through a crisis, or simply want an outside perspective on your thoughts, there’s no one who wouldn’t benefit from talking with a warm and experienced therapist. As well as exploring therapeutic ideas through our App + Articles, we also offer a range of online therapy services – including 1:1 psychotherapy, CBT, couples and group therapy.

LEARN MORE

Join our next 4-day non-residential City Retreat in the heart of London, designed to help you heal from your deepest emotional challenges in an atmosphere of friendship, learning and discovery. This is a chance to immerse yourself in the ideas and atmosphere of The School of Life and our psychotherapy team — and to come away with new ideas, perspectives and friends.

BOOK YOUR PLACE

We partner with businesses to equip their employees with the emotional skills they need to thrive at work – and grow as people.

We apply therapeutic ideas to the world of work, helping individuals and teams overcome the challenges they face, achieve their professional goals and solve the dilemmas of being human.

We’ve been creating life-changing books, tools and resources for over 10 years. Discover the very best products from The School of Life.