Work • Consumption & Need

Adverts Know What We Want – They Just Can’t Sell It to us

Patek Philippe is one of the giants of the global watchmaking industry, with revenues last year of just short of 750 million euros. For years now, they have been running a very distinctive series of adverts featuring parents and children. You’re sure to have glimpsed one somewhere.

In one example, there’s a father and son together in a motorboat, a scene which tenderly evokes filial and paternal loyalty and love. The son is listening carefully while his kindly dad is telling him about some aspect of seafaring. We can imagine the boy will grow up confident and independent – yet also respectful and warm. He’ll be keen to follow in his father’s footsteps and emulate his best sides. The father has put a lot of work into the relationship (one senses they’ve been out on the water a number of times, and when the boy was younger, there might have been marathon Lego building sessions in the bedroom) and now the love is being properly paid back. The advertisement understands our deepest hopes. Yet it is moving precisely because what it depicts is so hard to find in real life. Father-son relationships rarely go so well. There is neglect, rebellion and bitterness. Dad was too often away. The son is caught up in a bad group at school. There’s no chance to talk any more. But for a moment, thanks to Patek Philippe, we are afforded a glimpse of psychological paradise; no wonder if we are touched.

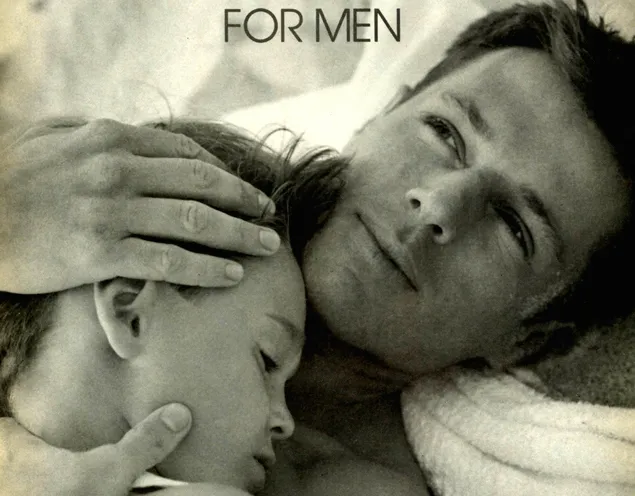

Or take this ad from Calvin Klein. The parents and children have tumbled together in a happy heap. There is laughter; everyone can be silly together, there is no more need to put up a front, because everyone here is trusting and on the same side. No one understands you like these people do. In the anonymous airport lounge, in the lonely hotel room, you’ll think back to this cozy group and miss them terribly. Alternatively, you might already miss those years, quite a way back, when it was all so easy. The kids are older now and the stresses are much greater. Only last week, there was a horrific row over drugs and mobile phones. Your relationship with your spouse is suffering too. Calvin Klein knows all this; it too has latched on to our deepest, and at the same time, most elusive inner longings.

Adverts wouldn’t work as well as they do if they didn’t operate with a very good sense of what our real needs are; what we really require to be happy. Their emotional pull is based on knowing us extremely well. We are creatures who hunger for sexual love, good family relationships, connections with others and the feeling that we are respected. Advertisers understand these needs so very well.

Yet, armed with this knowledge, they are unwittingly extremely cruel to us. For while they excite us with reminders of our buried longings, they refuse to do anything sensible or sincere to quench them adequately. They show us paradise, then don’t sell us anything with whose help we might reach it.

Of course, adverts do sell us things. Just rather inadequate things in relation to the hopes they arouse. Calvin Klein makes lovely cologne. Patek Philippe’s watches are extremely reliable agents of time-keeping. But it’s hard to see how these products are going to help us secure the goods our unconscious believed were on offer. A watch, or a bottle of scent – however excellent in their own way – don’t have the answers to our psychological needs (which impelled our purchases).

We’re often selling each other the wrong things; material things rather than the more important psychological tools we need. Business needs to get more ambitious, we should turn our energies to creating new kinds of products – as strange sounding today as a wrist watch would have seemed in 1500. We need the drive of commerce and industrialisation to get behind filling the world – and our lives – with products that really can help us to thrive, flourish, find contentment and manage our relationships well. Only this will help us to make real the lovely ideals which the adverts of today make us gaze at from far away.

At present, adverts often look slightly ridiculous if they are examined carefully. The teams of executive and creatives who came up with this image put a finger on some big concerns. They realise how much we long for companionship, confidence and a feeling of freedom. This ad is designed to enliven our hopes:

Yet all that is on offer to help us in our quest for a better life is a phone. It might be great but on its own can do little to help us find the feelings which the image evokes.

It’s common to complain that the advert is attempting to trick us into embracing a falsehood; trying to get us to believe that if only we buy the product we will get the other things too. It’s a recurrent theme in our relationships with advertisements.

In order to sell us its products, Google is tapping into one of our greatest emotional needs: the sense that we have properly explored the world and humanity. However, having evoked this grand need, the answer it proposes is humbly small: this is a call for us to spend a bit more time looking up a restaurant or cinema on Google Maps. That’s no terrible thing, but it’s rather a let-down given the emotional button that Google’s advert had skilfully pressed.

It can seem as if the adverts are trying to deceive us, alluding to emotional needs while in fact only catering to material ones. But, in fact, the problem does not usually lie with the advert, rather with the products on offer. The need for a sense of belonging or a sense of exploration are real, but a phone or map app, however good, probably aren’t the answer. The worries are much bigger than the products seem to understand.

The real crisis of Capitalism is that product development lags so far behind the best insights of advertising. Advertising has cottoned onto the fact that we would love to get help with the true challenges of life. We want to have better careers, stronger relationships, greater confidence. But products do not focus on those issues at all. The solution will come when producers actually begin to address the ambitious and important matters that adverts have so far merely known how to identify. Instead of asking how can we get people to buy a phone or a watch they have made, businesses should be seeking to create goods and services that really do help people find companionship, from and maintain strong families, be more courageous and cope better with the fear of missing out. These are the things – as the advertisers already understand – that we all really want.

In most adverts, the pain and the hope of our lives have been superbly identified, but the product is almost comically at odds with them. Manufacturers are hardly to blame. They are, in fact, the victims of an extraordinary problem of modern capitalism. We long to have strong relationships with our children, we desperately want the generations to feel loyal to one another and get on well. But we have been putting our highest creative efforts into minimising the size of cameras and speeding up the transmission of data. And so we have nothing better to offer ourselves – in the face of our troubles – than a slightly larger hand-held screen.