Leisure • Western Philosophy

Albert Camus

Albert Camus was an extremely handsome mid-20th century French-Algerian philosopher and writer, whose claim to our attention is based on three novels, The Outsider (1942), The Plague (1947), and The Fall (1956), and two philosophical essays, The Myth of Sisyphus (1942) and The Rebel (1951).

Camus won the Nobel prize for literature in 1957 – and died at the age of 46, inadvertently killed by his publisher Michel Gallimard, when his Facel Vega sports car they were were in crashed into a tree. In his pocket was a train ticket he had decided not to use at the last minute.

Camus’s fame began with and still largely rests upon his novel, The Outsider. Set in Camus’s native Algiers, it follows the story of a laconic, detached, ironic hero called Mersault – a man who can’t see the point of love, or work, or friendship – and who one day – somewhat by mistake – shoots dead an Arab man without knowing his own motivations and ends up being put to death – partly because he doesn’t show any remorse, but not really caring for his fate one way or the other.

The novel captures the state of mind defined by the sociologist Emile Durkheim as anomie, a listless, affectless alienated condition where one feels entirely cut off from others and can’t find a way to share any of their sympathies or values.

Emile Durkheim

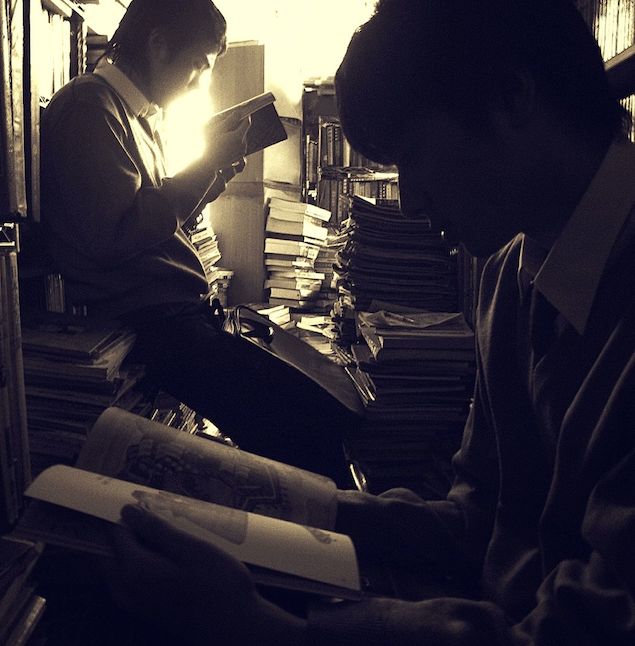

Reading The Outsider has long been an adolescent right of passage among French and many other teenagers – which isn’t a way of doing it down, for a lot of the greatest themes are first tackled at 17 or so.

The hero of The Outsider, Meursault cannot accept any of the standard answers for why things are the way they are. He sees hypocrisy and sentimentality everywhere – and can’t overlook it. He is a man who cannot accept the normal explanations given to explain things like the education system, the workplace, relationships and the mechanisms of government. He stands outside normal bourgeois life, highly critical of its pinched morality and narrow concerns for money and family.

As Camus put it in an afterword he wrote for the American edition of the book: “Meursault doesn’t play the game. He refuses to lie… he says what he is, he refuses to hide his feelings – and so society immediately feels threatened.”

Much of the unusual mesmerising quality of the book comes from the coolly-distant voice in which Meursault speaks to us, his readers.

© Flickr/Han Cheng Yeh

The opening is one of the most legendary in 20th-century literature and sets the tone: “Today mother died. Or maybe yesterday, I don’t know.”

The ending is as stark and as defiant. Meursault, condemned to death for a murder committed almost off-hand, because it can be interesting to know what it’s like to press the trigger, rejects all consolations and heroically accepts the universe’s total indifference to humankind: “My last wish was that there should be a crowd of spectators at my execution and that they should greet me with cries of hatred.”

Even if we are not killers and will ourselves be really quite sad when our mother dies, the mood of The Outsider is one we are all liable to have some experience of… when we have enough freedom to realise we’re in a cage, but not quite enough freedom to escape it… when no one seems to understand… and everything appears a bit hopeless…perhaps in the summer before we go to college.

© Flickr/Joan Sebastián Araújo Arena

Aside from The Outsider, Camus’s fame rests on an essay, published the same year as the novel, called The Myth of Sisyphus.

This book too has a bold beginning:

“There is but one truly serious philosophical problem and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living, that is the fundamental question of philosophy.”

The reason for this stark choice is, in Camus’s eyes, because as soon as we start to think seriously, as philosophers do, we will see that life has no meaning – and therefore we will be compelled to wonder whether or not we should just be done with it all.

To make sense of this rather extreme claim and thesis, we have to situate Camus in the history of thought. His dramatic announcement that we have to consider killing ourselves because life might be meaningless is premised on a previous notion that life could actually be rich in God-given meaning – a concept which would sound remote to many of us today.

And yet, we have to bear in mind that for the last 2,000 years in the west, a sense that life was meaningful was a given, accorded by one institution above any other: the Christian Church.

Camus stands in a long line of thinkers, from Kierkegaard to Nietzsche to Heidegger and Sartre who wrestle with the chilling realisation that there is in fact no preordained meaning in life. We are just biological matter spinning senselessly on a tiny rock in a corner of an indifferent universe. We were not put here by a benevolent deity and asked to work towards salvation in the shape of 10 commandments or the dictates of the holy gospels. There’s no road map and no bigger point. And it’s this realisation that lies at the heart of so many of the crises reported by the thinkers we now know as Existentialists.

A child of despairing modernity, Albert Camus accepts that all our lives are absurd in the grander scheme, but – unlike some philosophers – he ends up resisting utter hopelessness or nihilism. He argues that we have to live with the knowledge that our efforts will be largely futile, our lives soon forgotten and our species irredeemably corrupt and violent – and yet should endure nevertheless.

We are like Sisyphus, the Greek figure ordered by the gods to roll a boulder up a mountain and to watch it fall back down again – in perpetuity.

But ultimately, Camus suggests, we should cope as well as we can at whatever we have to do. We have to acknowledge the absurd background to existence – and then triumph over the constant possibility of hopelessness. In his famous formulation:

“One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

This brings us to the most charming and seductive side of Camus: the Camus who wants to remind himself and us of the reasons why life can be worth enduring – and who in the process writes with exceptional intensity and wisdom about relationships, nature, the summer, food and friendship.

As a guide to the reasons to live, Camus is delightful. Many philosophers have been ugly and cut off from their bodies.

Think of sickly Pascal

Crippled Leopardi

Sexually-unsuccessful Schopenhauer

Or poor peculiar Nietzsche

Camus was by contrast

– Very good looking

– Extremely successful with women: for the last 10 years of his life, he never had fewer than three girlfriends on the go, and wives as well

– And he had a great dress sense, influenced by James Dean and Humphrey Bogart. It isn’t surprising he was asked to pose by American Vogue

These weren’t all just stylistic quirks. Once you properly realise that life is absurd, you are on the verge of despair perhaps – but also, compelled to live life more intensely. Accordingly, Camus grew committed to, and deeply serious about, the pleasures of ordinary life. He said he saw his philosophy as “a lucid invitation to live and to create, in the very midst of the desert.”

He was a great champion of the ordinary – which generally has a hard time finding champions in philosophy – and after pages and pages of his denser philosophy, one turns with relief to moments when Camus writes in praise of sunshine, kissing and dancing.

Camus was an outstanding athlete as a young man. Once asked by his friend Charles Poncet which he preferred, football or the theatre, Camus is said to have replied, “Football, without hesitation.”

Camus played as goalkeeper for the junior local Algiers team, Racing Universitaire d’Alger (which won both the North African Champions Cup and the North African Cup in the 1930s).

The sense of team spirit, fraternity, and common purpose appealed to Camus enormously. When Camus was asked in the 1950s by a sports magazine for a few words regarding his time with the RUA, he said: “After many years during which I saw many things, what I know most surely about morality and the duty of man I owe to sport.” Camus was referring to the morality he defends in his essays: sticking up for your friends and valuing bravery and fair-play.

© Flickr/Don

Camus was a great advocate of the sun. His beautiful essay “Summer in Algiers” celebrates: “the warmth of the water and the brown bodies of women.” He writes: “For the first time in 2,000 years, the body has appeared naked on beaches… For 20 centuries, men have striven to give decency to Greek insolence and naivety, to diminish the flesh and complicate dress. Today, young men running on Mediterranean beaches repeat the gestures of the athletes of Delos.”

He spoke up for a new paganism, based on the immediate pleasures of the body: “I recall a magnificent tall girl who had danced all afternoon. She was wearing a jasmine garland on her tight blue dress, wet with perspiration from the small of her back to her legs. She was laughing as she danced and throwing back her head. As she passed the tables, she left behind her a mingled scent of flowers and flesh…”

© Flickr/Marrickville Library

Camus railed against those who would dismiss such things as trivial and long for something higher, better, purer:

“If there is a sin against life, it consists perhaps not so much in despairing of life as in hoping for another life and in eluding the grandeur of this one.”

In a letter he remarked: “People attract me in so far as they are impassioned about life and avid for happiness…”

“There are causes worth dying for, but none worth killing for.”

Camus achieved huge acclaim in his lifetime, but the Parisian intellectual community was deeply suspicious of him. He never was a Parisian sophisticate. He was a working-class pied-noir (that is, someone born in Algeria but of European origin), whose father had died of war wounds when he was an infant and whose mother was a cleaning lady.

It isn’t a coincidence that Camus’s favourite philosopher was Montaigne – another very down-to-earth Frenchman, and someone one can love as much for what he wrote as for what he was like.