Leisure • Art/Architecture

Andrea Palladio

In Europe and the US, the average person spends 84% of their life indoors: that is, inside architecture. Much of the rest of the time we are around buildings, even if we’re not paying them a great deal of attention. Despite this massive exposure, on the whole we’re not – as a culture – very ambitious about what buildings look like. We tend to assume that mostly the buildings we live around won’t be anything special and that there’s nothing to be done about this. We’ve come to imagine that great buildings are the unique and very expensive creations of genius-architects. You might travel to see great architecture on holiday perhaps but it’s hardly to be expected as standard at home. Vicenza, 25 miles inland from Venice, is one of the leading sites of global architectural tourism and for one reason: many of the works of Andrea Palladio are located in and around that town.

Andrea Palladio was born at the end of November in 1508 in Padua. He was an apprentice stone mason and later a stone carver. His real name was Andrea di Pietro della Gondola (i.e. Andrew, son of Peter the Gondolier). And it was only when he was around thirty years of age that he got involved in designing buildings himself – and his first important patron suggested a stylish name change, to Palladio.

[It’s not intuitively obvious how to say his name. A safe bet is to start with ‘pa’ (as in dad); then ‘lad’ as in ‘a bit of a lad’; and finish up with with a brisk ‘ay-oh’: pa-lad-ayoh.]

Over the next forty years of his working life, Palladio designed forty or so villas, a couple of town houses and a handful of churches. Not a huge list, given the amount of building that was going on at the time. For most of his career he had a mix of professional successes and setbacks; though during his sixties he finally emerged as the top architect in Venice – about the richest and most powerful city in the world at that time. He was a devoted father, but his two elder sons – who worked alongside him – died young. Palladio himself died in the summer of 1580. He was 71.

Palladio himself held views on architecture almost entirely opposite to those which are current today. His attitude can be summarised by two central ideas. First, architecture has a clear purpose, which is to help us be better people. And, second, there are rules for good building. Great architecture (he was convinced) is more of a craft than an art: it isn’t necessarily expensive and it is for everyday life, for farms, barns and offices, not only for the occasional glamorous project.

One: The Purpose of Architecture

We tend not to ask this question, it can easily sound naive or pretentious. Either you are supposed to know already or someone is about to launch into a complicated disquisition.

Palladio held that architecture has an important purpose – above and beyond the provision of floors, walls and ceilings. He thought that we should build in order to encourage good states of mind in ourselves and others. In particular, he thought architecture could help us with three psychological virtues: calm, harmony and dignity.

Encouragement for our better nature

Calm

He reduces what’s going on; all the elements in a room are centred, balanced, symmetrical. He only uses simple geometrical shapes. Generally, the walls are plain and neutral. There’s not meant to be much furniture. The serenity of the space is designed to calm us down; they are not trying to surprise or excite us. They invite us to focus and concentrate, to be less distracted.

Encouragement to be serene

Harmony

Palladio was obsessed with making sure that every element of a building fitted perfectly with every other.

‘A fine building ought to appear as an entire and perfect body, wherein every member agrees with its fellow, and each so well with the whole, that it may seem absolutely necessary.’

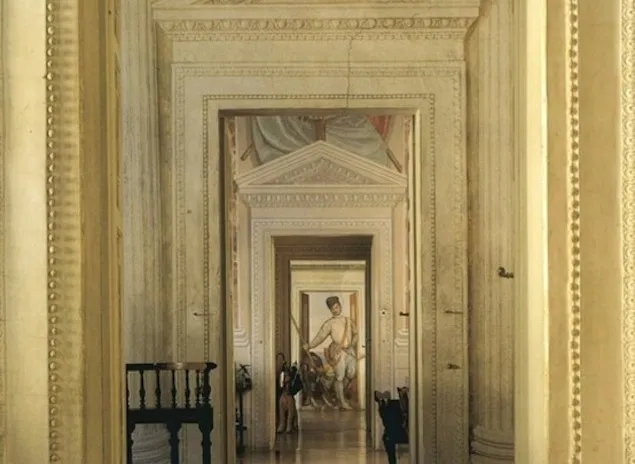

The design of a window is related to that of a door; every opening is aligned with every other; every room is a clear, simple shape; the doors always line up.

One door leads to another – Villa Barbaro

Powerfully coherent buildings are moving because they counter the natural tendency of life for things to get muddled, confused and compromised. They work against our anxiety that many of our concerns won’t line up neatly: that work and home life, sex and love, desire and duty will all be continually fighting one another. The building creates an environment in which we are provided with a limited – but real – sense of everything important coming elegantly together.

A portion of the world in which elements work harmoniously together

Dignity

One of the ambitions of Palladio’s architecture was to give greater dignity to parts of life that had been, unfairly, regarded as unworthy. And which, in his eyes, lacked the prestige they properly deserved.

At the Villa Barbaro – a farmhouse in the countryside about forty miles north of Venice – the barns and stables and grain stores are just as grand as the owner’s not especially large house. Rather than being hidden away or set at a distance, these working buildings are presented as honourable and important.

Villa Barbaro – the workers lived in the elegant wings

He wasn’t disguising the utilitarian reality of the farm, rather he was demonstrating its genuine (though generally underappreciated) dignity.

In directing architecture towards these psychological states, Palladio wasn’t flattering us. He wasn’t pretending that his buildings were reflecting what we’re normally like. He knew perfectly well that people tend to be (then as now) irate and agitated; that dignity is a mask that slips; that we get despondent. He wasn’t trying to give expression to ordinary human nature. In keeping with the long classical tradition, he believed that buildings should try to compensate for our weaknesses: encouraging us to be more collected, poised and measured than we manage to be day to day. We need serene, harmonious and confident buildings precisely because we’re not reliably like that. Ideally, architecture embodies our better selves. The ideal building is like the ideal person.

Palladio is classically pessimistic about our ability to hold onto ideas; the mind is leaky: we very easily lose contact with our own better nature; we’re very likely to forget, under pressure, what is important to us. The task of architecture is to provides us with the environment that continuously reminds about – and encourages us to become – who we really want to be.

Two: Rules

Of course, we accept that there are lots of useful rules – for airline safety, accounting practices or card games. But we’re generally suspicious of the idea that rules might be important around anything deemed cultural, intimate or creative: the idea that there might be beneficial rules of conversation, art, relationships or indeed of architecture. We tend to see rules as secondary, lacking originality. Like Aristotle, Palladio took the view that many creative undertakings (like writing tragedies, having conversations or cultivating friendships) should be understood as skills or crafts. They are learnable. According to a classical outlook, good outcomes in such areas are not simply to do with luck or chance. And rules ideally capture what it is we need to do in order to do them well.

In 1570, Palladio published his Four Books on Architecture.

It’s an early, and very distinguished, example of the ‘how to’ genre. It gives instruction on how to build. There’s a practical guide to digging foundations and how to judge the quality of cement and the various reliable ways of constructing walls and laying floors.

He also develops rules of proportion, based on simple mathematical ratios. The ancient Greek philosopher Pythagoras had famously discovered that two taught strings, one half the length of the other, sound harmonious when vibrated at the same time. The pleasing quality of the sound, he discovered, was governed by a simple mathematical principle. Palladio and others developed a visual equivalent of this.

The fancy surrounds are not the crucial thing. Without them, the window opening will still look lovely, because it is the proportions and not the decoration that make it harmonious. This meant that an equally beautiful building could be produced more cheaply (always one of Palladio’s chief concerns). Because the same proportions are beautiful irrespective of whether the building is made of marble, brick, concrete or wood.

And he went on to provide a wide range of simple rules for making buildings attractive: they should be symmetrical; there should be three, five or seven openings on a side – not an even number; rooms should have a simple geometrical shape, the length should be three-fifths of the width and the height three-fifths of the width.

Palladio saw himself as a craftsman. He was simply following a set of rules, which others could follow too. He was working against the idea that architecture requires special genius. The ideal of a pattern book is that visually elegant buildings can be put up as standard, as happened (to a significant extent under the influence of Palladio) in London and in many cities in the 18th century.

A central concern of the Four Books is to educate the potential client or the consumer of architecture. Often, we’re not very sure why we like or dislike buildings. We might have quite positive or negative reactions and say something is great or rather horrible. But if pressed for an explanation, we often find ourselves struggling. We find it difficult to say what it is about about one building that makes it attractive and what makes another unappealing. We’re tempted to say that it’s a purely personal matter, that taste in architecture is purely subjective. It’s a well-intended sentiment. But it’s also unfortunate. It plays into the hands of developers who have no concerns whatever for beauty – who are safe in the knowledge that they will never be taken to task for what they do.

Conclusion

Palladio’s ideas have resonated down the ages. But it isn’t when buildings have columns or make nods to ancient temples that they are necessarily at their most authentically ‘Palladian’. Buildings are Palladian when they are devoted to calm, harmony and dignity on the basis of rules which can (and should be) widely re-used. It’s then they display the same underlying ambition of which Palladio is a central exponent and advocate: that it should be normal for buildings to present us with a seductive portrait of our calmest and most dignified selves.

Some great modern ‘Palladian’ buildings:

Le Corbusier, The Villa Savoye.

Louis Kahn, Korman House

James Gorst, Leaf House