Self-Knowledge • Emotional Skills

Appreciation

It sounds peculiar, and a little patronising, to suggest that one of the major obstacles to contentment might lie in our failure to master the skill of Appreciation. For a start, we don’t tend to think that Appreciation even is a skill, it seems rather as if we are spontaneously endowed with the capacity correctly to judge what is worth treasuring; and so that we must be natively correct in our assessment of what is worthy of gratitude. It is in addition rather natural to trust that – unfortunately – most of what is truly worth treasuring is not yet in our possession.

Then, very occasionally, a rather surprising feeling can befall us. We land on something highly familiar and accessible to us, which we have not drawn value from in years, and are suddenly overwhelmed by a newfound sense of its importance, beauty and worth. It might be the view from the window, the way the sunlight is falling on the curtain, the stillness of the evening at the top of the house or the hand of our lover as it rests on the table in front of us. The memory of our previous neglect, combined with our new heightened awareness, pushes us to acknowledge some unknown flaws in our mechanisms of appreciation and humbly to wonder at how widely these may extend. We can end up on the cusp of a bold, huge and fruitfully disturbing thought: that we may already be far richer than we think; that our dissatisfactions may be more the result of a failure to draw value from what we already have than from the absence of what we long for.

On reflection, it truly does appear that one of our major flaws, and therefore causes of our unhappiness, lies in our difficulty with recognising the worth of some of what is already to hand, and which means that we yearn, often unfairly, for the imagined attractions of other places, people and things.

Fortunately, appreciation is a skill rather than – as it’s too often judged – a gift; one made up of a series of component parts, which it is eminently in our power to bolster in ourselves through a range of practices:

1. Defamiliarisation

Our dissatisfactions are partly caused by a dramatic facility to get used to things, by our mastery of the art of habituation. This can sometimes offer us important benefits. Before we’ve picked up the habit of driving, we have to be acutely conscious of everything that is going on as we sit at the wheel; our senses are highly alert to sounds, lights, movement and to the sheer alarming implausibility of steering a box of steel at speed through the world. This hyper-awareness can make driving a test of nerves. However, after years of practice, it gradually becomes possible to drive for miles while hardly thinking about changing gears or indicating. Our actions become unconscious, and we can ponder central themes of existence while negotiating a roundabout.

But habit can just as well become a cause of misfortune, when it renders us prone to barely register things that, though familiar, deserve careful engagement. Instead of editing out the lesser things, so that we can concentrate on what is crucial (as ideally happens on the road), we end up editing out elements of the world that should be central to our contentment.

Improving our talent at appreciation therefore requires us to go in the opposite direction of habit, willingly to de-familiarise ourselves to our environment, to look upon objects and people as if we had never laid eyes on them before, so that their worth can again become apparent to us.

We can learn something of what this involves every time we are ill. Having to sequester oneself in bed for a few days is – ostensibly – far from desirable, but it has important things to teach us about the art of appreciation. Picture that you have come down with a bad flu. For what seemed like an age, you could hardly open your eyes, let alone generate even a single coherent thought. Someone brought you a cup of lentil soup, but you couldn’t bear to touch it. As you lay in bed, most themes of your life took a back seat. It didn’t seem to matter what was happening at work. You didn’t have the energy to get roused by the little things that so often irritate you. You took a break from scanning the news. You didn’t feel obliged to respond to texts and emails. Your sexual appetites were in recession and stopped occupying your mind. Then, finally, came a slow return to health. You slept well last night and now so much that you’d never otherwise notice have become sources of positive pleasure. Being able to breathe easily is interesting: how nice to feel the air drawing through the paranasal sinuses; it’s lovely to be able to swallow without wincing. You can focus on the the back of your head – there’s not a trace of the throb that’s been your companions for the last 48 hours. Your eyes feel energetic. You brain is coming alive. Feeling hungry is really very nice. The mere act of standing up (without feeling dizzy or weak) is a pleasure in itself. It’s rather fascinating to put on proper clothes and going outside seems, briefly, like a treat.

As we re-emerge into the world, we are remaking acquaintance with things that had been taken for granted but now seem fascinating, touching and wondrous. You haven’t used a house key for a few days and you see it anew as a beautifully intricate machine that by a process you almost (but don’t quite) understand can manoeuvre the small tongue of steel that is the only real barrier between your private domestic civilisation and the barbarian world into its snug little slot. You turn the key this way and that in the lock for the sheer pleasure of hearing the decisive click of closure alternate with the flat thud of release. A shoelace seems astonishing: how odd that we tie ourselves into our shoes with little bits of string and that our culture has very strict ideas about what the knot should be like – theoretically you could knot the ends together fifty times into a large ball and it’s curiously tempting to give it a go. One is returned to the condition of a child who has just mastered the art of doing up a zip and for whom zips are still (what they always really are) wondrous little pieces of portable engineering, generously sewn into onto one’s clothes for entertainment value.

We’re not literally required to be ill to have these pleasures. Potentially we could discover them by the pure exercise of imagination. The task is to see without being ill what we mostly have to wait for the special prompt of a few days of bed-ridden retreat.

An associated, relevant strategy was once explored in the 18th century by the French writer Xavier de Maistre. De Maistre was wounded in a duel and had to spend 42 days confined to his bedroom. For a while he was deeply bored and frustrated. He wished he could escape and travel to exotic places. Then he had a brilliant idea. He decided to take a holiday and go for an adventure – not to the Indies or the Swiss alps, but around his own room, a journey he would record in the mock-serious journal he wrote and which made his name entitled A voyage around my bedroom. De Maistre treated the familiar items of his room – a chair, his bed, the window – as if they were remarkable novelties and became genuinely delighted. He was re-sensitised to objects that had lost their charm. He realised that there was so much he hadn’t noticed adequately. He thought he knew his bed perfectly already, but he hadn’t properly paid attention to all its different regions; he’d never put his head exactly in the middle and seen what it looked like from there – a kind of soft, blanketed plateaus with a little hill rising up at one end (thanks to the pillows) with sharp cliffs on three sides. He’d never looked closely at the back corners of a drawer (though he’d opened it a thousand times to extract a pair of socks); he’d paid – up to now – scant attention to how the sunlight makes patterns on the curtains in the early morning; he hadn’t listened carefully to every sound he could hear form the outer world. The key to existence, de Maistre realised, is not to seek out what is actually new. It is to bring a fresh mindset to what we already know but have – long ago – forgotten to notice.

2. Contrast & Context

There is another way to hone our talents at appreciation: to learn to deprive ourselves for a time of what we did not even know we depended on – in order to bring its value to light. The bored spouse spends a weekend on their own. The dissatisfied child swaps places with a student from a more modest background. The middle class European books a holiday to Comuna 13, in the San Javier district of Medellín, the second largest city in Colombia.

Here groups of young men armed with planks of wood roam the alleyways extorting money. Houses are made of bits of tin, old doors, the occasional lump of concrete, oil drums and tarpaulin sheets. Sofa carcasses thrown onto rubbish tips in the first world are covered in strips of office carpet. Open sewers, choked with filth, run between houses. People spend their days picking up refuse in a gigantic dump. It’s an ideal holiday destination.

In the 18th century, successful young men went on Grand Tours to complete their education. They travelled to Venice, Florence, Rome and Naples and looked at pictures and statues from the Renaissance and the Ancient World. Their journeys were based on an idea that what their participants most lacked, and might most severely be undermined by lacking, was high culture. They had to undertake such journeys – they needed to know about Titian and Veronese and key moments in Roman history – in order to become fully human. This distinctive theory has had a huge impact. It explains why, at most times of year, the Uffizi in Florence and the Villa Borghese in Rome are packed. We remain the heirs of the notion that high culture is necessary to complete us.

But there are, in truth, a great many other things we may lack as badly. Most of us are continually disenchanted with our circumstances. It seems impossible not to keep thinking about the people one envies, the ones who made it big. Our countries appear to be intolerably badly managed, dispiriting and coarse. The new supermarkets are unsightly and there’s nothing uplifting on television. There seems so little to be grateful for from day-to-day.

That is why we need, perhaps more urgently than we need to go to Florence, to take a trip to Comuna 13. Of course we know, in theory, that we’re lucky, all of us in the first world; we’ve known it ever since we were intimidated into finishing what was on our plates by tales of malnourished children in foreign lands. But it’s really only when one spends one’s first night in Comuna 13 that the truth starts to sink in. There are no street lamps. Girls of 12 are selling themselves on street corners. The police will rob and possibly rape you. Guns go off hourly. If there is a fire, no fire engines can get to the scene; everything is burned. A gash on the leg from a ragged piece of metal or a sliver of broken glass can prove fatal. Your food has shit in it. If you are seriously ill; you die. A luxury would be a biro, some toothpaste, a clean sheet, a door with a lock. Comuna 13 is an education in appreciation. It teaches us to see – and admire – things we have scarcely noticed before. An 18th-century aristocrat would typically bring home a painting or a statue as a memento of their Grand Tour. They would put it in a prominent place at home: above the fireplace or in the hallway, so that they would see it everyday and so that the lessons of the trip would be kept fresh. Today, on returning from a week’s stay in Comuna 13, one might keep a bit of corrugated iron or a photo of the rain flooding straight through the roof of a family’s one-room home, soaking them and their three young children to the bone.

It is with comparable ambitions around appreciation that for many centuries, it was thought important for people to be surrounded by visible and stark reminders of death. These ‘memento mori’, as they were known – usually featuring symbols of the fragility of existence, like a flower, an hourglass and a skull – were designed not to depress us and drain energy from life, but precisely the opposite: to make us aware of the preciousness and possible rarity of every passing hour.

3. The Eyes of Others

What we call ‘glamour’ usually lies elsewhere: in the homes of people we don’t know, at parties we read about, in the lives of people who have been adept at turning their talents into money and fame. It’s in the nature of media-dominated societies that they will by definition expose us to a great deal more glamour than most of us have the opportunity to participate in. We are left peering, painfully, through the window at enticements beyond. Commercial images help to generate the longing for the higher realms promised by contemporary capitalism, it is they that give us a ringside seat on the holidays, professional triumphs, love affairs, casual evenings out and birthdays of an elite who we are condemned to know far better than they know us.

Yet if images carry a lot of the blame for instilling a sickness in our souls, they can also – occasionally – be credited for offering us antidotes. It is in the power of art both to disgust us with the apparent tedium and colourlessness of our condition and to effect intelligent reconciliations with it. Some of the cure for our lack of appreciation lies in looking at the world through the eyes of more sensitive, alert and grateful others, that is, through the eyes of artists.

Before certain works of art, we feel our appreciation of supposedly banal elements being reignited. The evening sky, a tree being blown by the wind on a summer day, a child sweeping a yard, or the atmosphere of a diner in a large American city at night are promptly revealed as not merely dull or obvious motifs but arenas of interest and complexity. An artist will find ways of foregrounding the most poignant, impressive and intriguing dimensions of a scene and fixing our attention on these, so that we will give up our previous scorn and start to see in our own surroundings a little of what Constable, Gainsborough, Vermeer and Hopper managed to find in theirs.

Edouard Manet, Bunch of Asparagus (1880)

Aside from chefs, gourmands and farmers, few people in nineteenth-century France would have been likely to detect anything especially interesting in asparagus – that is, until Edouard Manet painted a tightly wrapped bunch in 1880 and thereby called attention to the inherent wonder of this spring vegetable’s yearly apparition. However exemplary Manet’s technical skills may have been, his painting achieves its stunning effect not by inventing the charms of asparagus but by reminding us of qualities which we knew existed but which we have overlooked in our spoilt and habituated ways of seeing. Where we might have been prepared to recognise only dull white stalks, the artist observed and then reproduced vigour, colour and individuality, recasting his humble subject as an elevated and sacramental object through which we might access a redeeming philosophy of nature and rural life.

In any essay about the painter Chardin, Marcel Proust imagines a jaded and bored young man falling into depression because of the banality of his surroundings. He gets irritated by what he sees as domestic disorder and trivia. In the kitchen someone has left a hideous cabbage and an old dishcloth on the table, along with a boring, very modest jug and some sorry-looking carrots. He feels it’s all a bit squalid – and wishes he could live a more elegant, glamorous and refined life. Proust pictures himself coaxing this young man out of his mood by recommending that he visit the Louvre, and in particular, the galleries containing the works of the great 18th century still-life painter, Chardin. In these prestigious surroundings, the young man would see a painting of, not a palace or a yacht, a fine restaurant or a party, but of a cabbage, an old dish cloth and a boring jug.

However – guided by Chardin – the young man would (Proust hoped) start to see the charm and loveliness of just the things he’d earlier found merely annoying. The transformation of perception would come about by following the painter’s attention to detail. The cabbage isn’t really disgusting: it is composed of a beautiful variety of shades greens – mint, myrtle and viridian. It has lived close to the soil, it’s been drenched by the rain at night and coaxed into maturity by the sunshine; the old cloth has deep, rolling folds (like the fall of a toga); the simply jug is quietly dignified; its shape is ancient (though it was made only a few years ago in a factory on the outskirts of Paris); and together they point to something wonderful and completely ordinary: heat, water and few roots and leaves can slowly combine to produce a warming, nourishing soup. Life, these things tell us, could be simple and satisfying. In the language of the kitchen they are preaching a wisdom for the whole of existence.

From the late 1970s onwards, two German photographers, Hila and Bernd Becher, turned their lenses to some particularly unloved parts of the industrial landscape. They photographed grain silos, warehouses, turbines and water towers; all deemed eyesores and blights on the landscape, relics of a clumsy period of bleak, utilitarian industrial design.

Hila and Bernd Becher, Water Towers (1980)

But the Bechers disagreed and developed a particular method for helping others see the charms of these structures. Their approach was to group a whole lot of images together in order to educate our perception. Instead of seeing the towers as all pretty much the same, we could start to get sensitive to little differences. One of them – at the top right – is a bit like a space-rocket, while another (on the left in the middle row) has a series of supportive V-shaped arches that would have charmed a late-medieval architect. One develops preferences and relationships – the top left tower is more homely, the bottom right one is severe.

Art lends prestige, and when it is not around, when it has not yet caught up with our reality, we can feel an aching envious sense that the realm of beauty and interest is utterly removed from our circumstances. It is helpful to realise that this feeling that glamour is elsewhere has always been present and moreover, present in places where we now, thanks to art, have no problem identifying some value. We shouldn’t invariably blame the places we’re in, we should be aware that we damn them because artists have not yet arrived to open our eyes to them. The challenge for modern artists is to open our eyes to the charms of many distinctively modern landscapes – which means, predominantly, landscapes marked by technology and industry. The first impulse is to protest that there can be nothing beautiful in water towers, motorways or shipyards. But how wrong we would be to remain stuck here. There can be as much beauty here as in a set of asparagus or the head of a cabbage.

We labour under the mistaken assumption that what people want is a fixed factor; when it is in fact dramatically malleable, contingent and divergent. The most powerful and charming proof of this lies in the history of culture, which repeatedly shows us that, under the right encouragement, large groups of people can become highly sensitive to features which, in other societies or eras, go entirely unnoticed. Culture demonstrates that there are far fewer limits to what we can be led to appreciate than we might imagine in our cautious moments.

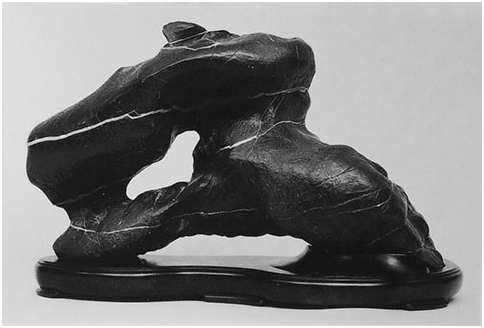

Take rocks. In 826 AD, during China’s Tang dynasty, a middle-aged civil servant, Bai Juyi, was taking a stroll around Lake Tai in eastern China – when his eye was caught by a pair of large, oddly shaped but distinctly pleasing rocks. So struck was he by their form, full of an ancient nobility and endurance, that he had them shipped back to his home and wrote a poem about them, A Pair of Rocks, now one of the most well-known works in Chinese literature. Bai Juyi admitted that his rocks were not typically beautiful, they were worn and dark and their undersides distinctly mossy. But the rocks seemed in their own way eloquent bearers of the tenets of Daoism, which urges us to keep the mighty forces of the universe constantly in mind and to accommodate ourselves serenely to their demands. Bai Juyi had the rocks placed on his desk, so he could be inspired by their suggestions of equanimity and patience.

Turning my head around, I ask the pair of rocks:

‘Can you keep company with an old man like myself?’

Although the rocks cannot speak,

They promise that we will be three friends.

Bai Juyi’s advocacy set off a wave of enthusiasm and was the foundation of an important new sector in China’s artistic economy. Stones began to be tracked down in the most inaccessible places, they were mounted on wooden bases, traded for large sums and installed around the houses of the wealthy. Cultivated people were now expected to have an appreciation of gongshi or spirit stones – which were valued as highly as any painting or calligraphic scroll. The most favoured rocks were the dark glossy kind quarried from the limestone of Lingbi, in the northern Anhui province. The best examples might cost as much as a house.

Lingbi Rock

In the first decade of the twelfth century, a civil servant called Mi Fu was appointed magistrate in Huaiyang province. On arrival, he attended a formal meeting at his official residence with all the administrators of the region. They stood waiting for him in the front garden in a position of solemn reverence, but as he walked towards them, Mi Fu committed a sudden and shocking breach of protocol. His gaze was diverted by an unusually large and interesting rock in the garden. Instead of offering his respects to his hosts, Mi Fu bowed ceremoniously to the rock, addressed it as ‘Elder Brother’ and made an elaborate speech in its honour. Only after fully expressing his devotion did Mi turn to his flabbergasted hosts and said hello. Using this incident to celebrate the wisdom of showing respect for natural forces rather than paying heed to social etiquette, China’s painters made the moment central to the Chinese artistic canon – almost as significant as the Annunciation has been in the Western tradition.

Guo Xu, Mi Fu and Elder Brother Rock (1503)

Hô Ryôn, Mi Fu Paying Homage to a Rock (1892)

The Chinese love of rocks reminds us of how much there remains for us to have our eyes opened to – and of how much that imposing category – the desirable – remains open to advocacy, waiting for us to understand the nature of our own pleasures. At any stage of history a culture may be negligent – it may be generally preoccupied only with a limited range of experiences that it teaches us to look to for satisfaction and fulfilment. The loudest voices in a culture – the most popular songs and games, the most conspicuous adverts, the funniest comedians, the biggest celebrities – may actually never have told us anything much about a whole range of things that can be sweet, delightful, moving or charming. We may very well grow up fully alive to the very real pleasures of fine dining, attending the Olympic opening ceremony or of flying business class: but entirely unprimed to recognise the attractions of a gnarled eroded rock.

So much of what there is to enjoy is currently under-rated by what might be called our collective ideology, that is, the elaborately constructed, inherited vision of how to live that has come, through familiarity and the endless prompts of peer pressure, to feel instinctive and natural.

4. Ritual

Every so often, you encounter a fig. It might turn up as a decorative aside to a dessert at a smart restaurant you occasionally go to when you want to mark a special occasion; from a couple of years back you remember there were baskets of them in the market in Cadiz which caught your eye, but you couldn’t pluck up the courage to joins the bustle at the stall and actually buy some; your sister puts them in the adventurous salads she sometimes serves; and they’re in the supermarket somewhere but you’re usually in hyper-focused mode there and race as fast as possible to buy the things you always buy.

Between these sporadic meetings you don’t think much about figs at all. Their existence is just one of a billion facts of which you are peripherally, passively aware. But when a fig does come your way, you are always rather charmed. The colours inside are lovely, of course. And the slightly dry texture of the flesh and its quiet taste are pleasant. You like figs, you remind yourself. And then it might be half a year before another lands in front of you on a plate. You’re hardly even sure when their season is (do they even have one?).

It’s a curious type of situation: there’s a small pleasure we have, but we leave having it very much to chance. And even when we do have the opportunity, often a lot of other things get in the way: the conversation takes a lively turn, your little nephew starts to wail in his bassinet; the combination is a bit unfortunate (the cacao bean chocolate was very nice but it annihilated the figs).

To work against this randomness, we need to invoke an idea that initially can sound a bit remote: ritual. We might initially associate ritual with archaic ceremonies, like a coronation, or with cultish gatherings. But there are more helpful images: the tiny ritual of blowing out the candles on a birthday cake and making a wish before cutting the first slice – slightly garbled traces of rather nice ideas: a birthday marks the end of one year of life and the beginning of the next, we should ideally focus our minds on transience and hope. And maybe the ritual once was more explicitly geared to helping us do this.

When we boil it down to its essence, the point of a ritual is to mandate a set of actions and attitudes, in order to get us into a valuable state of mind. It is – like a recipe – a set of rules that, if we follow them carefully, will bring about a certain result; not in this case a bowl of watercress soup or a crème brûlée but, rather, a state of heightened appreciation. Unlike a recipe a ritual usually comes with instructions about when you have to do it. Recipes leave it up to us – when you happen to feel like making a risotto, here’s what to do. But a ritual includes directions about when you should do it – every 365 days after your birth, when the new moon rises or when the cherry or plum trees are is in blossom (as with Hanami, ritualised picnics in Japan devoted to an appreciation of the transience of natural beauty). The ritual comes with a date; it makes an appointment in your diary, placed there by your culture. The ritual is rightly worried we’ll forget to pursue a particular pleasure – so it comes with a reminder.

Often with a ritual, the details have been honed and refined over a long period of time. People have thought quite hard how to get the most out of what they were doing. Rituals frequently invite us to quite specific patterns of thought and action. The Jicarilla Apache of New Mexico, for example, have an elaborate ceremony for adolescent girls which lasts for several days, the girls must wear special costumes and must pay close attention to particular stories and songs – designed to foreground a range of admirable qualities. The ritual is hugely ambitious because it aims to transform how they think about themselves and how they see their place in society.

If we were to invent a ritual around appreciation of the fig it could go like this: every Tuesday, after work, we’ll pick up some figs from the grocery opposite the train station. Place the fig on a plain white plate the first few times, the better to concentrate on the delicate, cool, green hues of the skin. Later you can experiment with another background: celadon or maybe black. Before you do anything else, take a moment to contemplate the essential strangeness of this small fruit. It could have evolved more like an acorn: highly effective from the point of view of propagation, but alien to the human system. It could have been more like the strawberry – so sweet and obviously charming as to be already utterly familiar. The fig, at this moment, is our point of entry. With a very sharp knife, cut it into quarters, lengthwise. The need for sharpness doesn’t arise from hardness but because they are soft, blunt pressure would spoil them. The edges of the pieces should be clean and the inner surface perfectly flat. Look at the tints and hues of the flesh. For 15 seconds, imagine you are a painter, trying to portray the pattern: make your eyes stick with it. Think of the tree it came from. This particular piece of fruit might have ripened in a plastic tunnel outside Basingstoke, but its ancestors flourished in historic times in Palestine or in Sicily and figured in the parables of tribes. Squeeze a few drops of lemon onto the sliced flesh – some will miss (it’s hard to aim with a lemon). This will intensify the flavour. Finally, take a bite. Concentrate first on the texture. Then, with a second bite focus on the taste. The ritual of the fig should last about seven minutes.

The ritual reminds us what to do in order to have a nicer time. It operates with a benign idea of rules and regulations. They’re not, in this case to stop us doing something that might be rather convenient at this moment. Instead they guide us to having a better time. This approach to rules is a revision of the Romantic ideal of spontaneity, the luck moment, which is excited by ideas of happy accidents and chance encounters. It’s not that these are always terrible ideas at all. It’s just that they aren’t the only template we need. If we only follow them a lot of good things won’t happen, or will happen only very rarely, when your sister just happens to take it into her head to ask you round to lunch.

Small pleasures need rituals. The irony (as it were) of the small pleasure is that it isn’t intense enough usually to force itself upon – we don’t become addicted or obsessed; the pull is much weaker than that of sex or video games or drinking wine or wolfing down a bar of chocolate; these are pleasures we need no reminding of, and we often have to painfully struggle to limit their sway in our lives. With small pleasures it’s the opposite. We are more likely to lose touch with them. They easily get crowded out. We actively need to build up their presence in our lives.

5. The Role of Price

We don’t think we appreciate things in relation to how much they cost, but we do. We don’t think we hate cheap things – but we frequently behave as if we rather do. Consider the pineapple. Columbus was the first European to be delighted by the physical grandeur and vibrant sweetness of the pineapple – which is a native of South America but which had reached the Caribbean by the time he arrived there. The first meeting between Europeans and pineapples took place in November 1493, in a Carib village on the island of Guadaloupe. Columbus’s crew spotted the fruit next to a pot of stewing human limbs. The outside reminded them of a pine cone, the interior pulp of an apple.

But pineapples proved extremely difficult to transport and very costly to cultivate. For a long time only royalty could actually afford to eat them: Russia’s Catherine the Great was a huge fan as was Charles II of England. A single fruit in the 17th century sold for today’s equivalent of GBP 5000. The pineapple was such a status symbol that, if they could get hold of one, people would keep it for display until it fell apart. In the mid-eighteenth century, at the height of the pineapple craze, whole aristocratic evenings were structured around the ritual display of these fruits. Poems were written in their honour. Savouring a tiny sliver could be the high point of a year.

Charles II being offered the first pineapple ever successfully grown in England, by the royal gardener, John Rose (1675)

The pineapple was so exciting and so loved that in 1761, the 4th earl of Dunmore built a temple on his Scottish estate in its honour:

And Christopher Wren had no hesitation in topping the South Tower of St Paul’s with this evidently divine fruit.

South Tower of St Paul’s Cathedral, Christopher Wren (1711)

Then at the very end of the 19th century, two things changed. Large commercial plantations of pineapples were established in Hawaii and there were huge advances in steam-ship technology; production and transport costs plummeted and, unwittingly, transformed the psychology of pineapple-eating. Today, you can get a pineapple for around GBP 1.50.

It still tastes exactly the same. But now, the pineapple is one of the world’s least glamorous fruits. It is never served at smart dinner parties and it would never be carved on the top of a major civic building.

The pineapple itself has not changed; only our attitude to it has. Contemplation of the history of the pineapple suggests a curious overlap between love and economics: when we have to pay a lot for something nice, we appreciate it to the full. Yet as its price in the market falls, passion has a habit of fading away. Naturally, if the object has no merit to begin with, a high price won’t be able to do anything for it; but if it has real virtue and yet a low price, then it is in severe danger of falling into grievous neglect.

It’s a pattern that we see recurring in a range of areas. For example, with the sight of clouds from above. In 1927, a hitherto unknown air mail pilot called Charles Lindbergh became the first man to complete a solo crossing of the Atlantic in his fragile plane, The Spirit of St Louis.

For hours, he flew in the most arduous conditions, braving wind, rain and storms. He saw clouds passing below him and distant thunder claps on the horizon. It was one of the profoundest moments of his life. He was awestruck and felt he was becoming, for a time, almost God-like. For most of the twentieth century, his experience remained rare and extremely costly. There was therefore never any danger that the human value of crossing an ocean by air would be overlooked.

This lasted until the arrival of the Boeing 747 and the cheap plane ticket in the summer of 1970. The jumbo fundamentally changed the economics of flying. The experiences of gazing down at clouds and seeing the world spread out stopped being (as it had been for Lindbergh) a life-changing encounter; it started to feel commonplace and even a little boring. It became peculiar to wax lyrical about the red-eye to JFK or a mention of a spectacular column of clouds that one had spotted shortly after the arrival of the chicken lunch. A trip that would have mesmerised Leonardo da Vinci or John Constable was now passed over in silence.

The view from the plane window underwent an economic miracle that led to a psychological catastrophe: its cost dropped and it ceased to matter, though its real value hadn’t changed.

Why, then, do we associate cheap prices with a lack of value? Our response is a hangover from our long pre-industrial past. For most of human history, there truly was a strong correlation between cost and value: the higher the price, the better things tended to be – because there was simply no way both for prices to be low and quality to be high. Everything had to be made by hand, by expensively trained artisans, with raw materials that were immensely difficult to transport. The expensive sword, jacket, window or wheelbarrow were simply always the better ones. This relationship between price and value held true in an uninterrupted way until the end of the 18th century, when – thanks to the Industrial Revolution – something extremely unusual happened: human beings worked out how to make high quality goods at cheap prices, because of technology and new methods of organising the labour force.

If you live in a craft-based society, the quality of any object invariably depends upon how much skilled labour went into producing it. In the 15th century, swords and helmets made by the Missaglias family in Milan were especially pricey. But that was because they were especially skilled, and produced armour that was stronger, lighter, better balanced and more cleverly designed than anyone else. It was a general principle: a more expensive cloak would be more durable, warmer and more elegantly decorated than a cheaper version. A more expensive window would let in more light, keep out more draughts, open more easily, and last in good condition much longer than its less expensive rivals: it would be a more skilfully made product constructed from more durable materials.

On the back of this long experience, an entrenched cultural association has formed between the rare, the expensive and the good: each has come to rapidly suggest the other, and the natural-seeming converse is that things which are widely available and inexpensive come to be seen as unimpressive or unexciting.

Sallet and armor by Antonio Missaglia (1450)

In principle, industrialisation was supposed to undo these connections. The price would fall and widespread happiness would follow. High quality objects would enter the mass market, excellence would be democratised.

This promised to be an exciting moment and evangelists regularly proclaimed a new age, where universal political suffrage would be accompanied by material dignity and honour for every social class.

In 1911, Henry Ford started developing the car assembly line, which replaced the slower individual skilled worker. The price of cars came down quickly so that it became possible for ordinary workers to afford cars themselves.

The designers of the Bauhaus movement in 1920s Germany were similarly fired up in their work by the idea of creating household items that would be both highly attractive and very cheap, available to anyone on even the most modest of salaries.

The promise of modernity: Nice chairs, desks, lamps and rugs for everyone

However, despite the greatness of these efforts, instead of making wonderful experiences universally available, industrialisation has inadvertently produced a different effect: it has seemed to rob certain experiences of their loveliness, interest and worth.

It’s not – of course – that we refuse to buy inexpensive or cheap things. It’s just that getting excited over cheap things has come to seem a little bizarre. One is allowed to get very worked up over the eggs of the sturgeon (£100 for a small pot); but have to be very circumscribed about one’s enthusiasm for the eggs of a chicken (12 for £2). There is an intimidating hierarchy operating in the background, shaping what we are grateful for and feel that we lack and must have.

The price tells us: something very special is going on here. But it may be going on in the cheaper thing too…

The tragedy for our relationship to money is that the hierarchy operates in favour of the expensive things, which means that very often we end up feeling that we can’t afford good things and that our lives are therefore sad and fatefully incomplete. The money hierarchy is constantly making us feel impoverished, while the hidden truth is that there are in fact more good things within our grasp than we believe (and tend to notice only when we are dying or recovering from a bad illness). We are rich enough to purchase the superlative egg of the chicken; but we don’t experience our wealth here; we are left lamenting our inability to buy the hugely expensive (but not actually much nicer) egg of the almost infertile and evasive Iranian sturgeon.

How do we reverse this? The answer lies in a slightly unexpected area: the mind of a four year old. Here he is with a puddle. It started raining an hour ago, now the street is full of puddles, and there could be nothing better in the world; the riches of the Indies would be nothing next to the pleasures of being able to see the rippling of the water created by a jump in one’s Wellingtons, the eddies and whirlpools, the minute waves, the oceans beneath one…

Children have two advantages: they don’t know what they’re supposed to like – and they don’t understand money – so price is never a guide of value for them. They have to rely instead on their own delight (or lack of it) in the intrinsic merits of the things they’re presented with, and this can take them in astonishing (and sometimes maddening) directions. They’ll spend an hour with one button. One buys them the £49 wooden toy made by Swedish artisans who hope to teach lessons in symmetry and finds that they prefer the cardboard box that it came in. They become mesmerised by the wonders of turning on the light and therefore think it sensible to try it 100 times. They’d prefer the nail and screw section of a DIY shop to the fanciest toy department (or the national museum).

This attitude allows them to be entranced by objects which have long ago ceased to hold our wonder. If asked to put a price on things, children tend to answer by the utility and charm of an object, not its manufacturing costs. This leads to unusual but – we recognise – more rightful results. A child might guess that a stapler costs a hundred pounds and would be deeply surprised, even shocked, to learn that the USB stick can be had for just over one pound. Children would be right, if prices were determined by human worth and value, but they’re not; they just reflect what things cost to make. The pity is, therefore, that we treat them as a guide to what matters, when this isn’t what a financial price should ever be used for.

An object worthy of immense wonder: now ignored

But at a certain age, something very debilitating happens to children (normally around the age of eight). They start to learn about ‘expensive’ and ‘cheap’ and absorb the view that the more expensive something is, the better it may be. They are encouraged to think well of saving up pocket money and to see the ‘big’ toy they are given as much better than the ‘cheaper’ one.

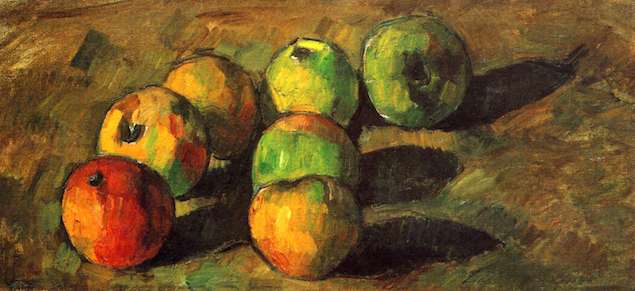

We can’t directly go backwards, we can’t forget what we know of prices. However, we can pay less attention to what things cost and more to our own responses. The people who have most to teach us here are artists. They are the experts at recording and communicating their enthusiasms which, like children, can take them in slightly unexpected directions. The French artist Paul Cézanne spent a good deal of the late nineteenth century painting groups of apples in his studio in Provence. He was thrilled by their texture, shapes and colours. He loved the transitions between the yellowy golds and the deep reds across their skins. He was an expert at noticing how the generic word ‘apple’ in fact covers an infinity of highly individual examples. Under his gaze, each one becomes its own planet, a veritable universe of distinctive colour and aura – and hence a source of real delight and solace.

The apple that has only a limited life, that will make a slow transition from sweetness to sour, that grew patiently on a particular tree, that survived the curiosity of birds and spiders, that weathered the mistral and a particularly blustery May is honoured and properly given its due by the artist (who was himself extremely wealthy, the heir of an enormous banking fortune: it seems important to state this, just to make sure that Cézanne wasn’t just making a virtue of necessity and would have worshipped gold bullion if he’d had the chance. He did; and he didn’t). Cézanne had all the awe, love and excitement before the apple that Catherine the Great and Charles II had before the pineapple: but Cézanne’s wonderful discovery was that these elevated and powerful emotions are just as valid in relation to things which can be purchased for the small change in our pockets. Cézanne in his studio was generating his own revolution, not an industrial revolution that would make once costly objects available to everyone, but a Revolution in Appreciation, a far deeper process, that would get us to notice what we already have to hand. Instead of reducing prices, he is raising levels of appreciation; which is a move that is perhaps more precious to us economically – because it means that we can suddenly get a lot more great things for very little money.

Some of what we find ‘moving’ in an encounter with the apples is that we’re restored to a familiar but forgotten attitude of appreciation, that we surely once knew in childhood when we loved the toggles on our rain jackets and found a paperclip a source of fascination and didn’t know what anything cost. Since then, life has pushed us into the world of money where prices loom too large, we now acknowledge, in our relation to things. While we enjoy Cézanne’s work, it might also unexpectedly make us feel a little sad: the sadness is a recognition of how many of our genuine enthusiasms and loves we’ve had to surrender in the name of the adult world. We’ve perhaps given up on too many of our native loves. The apple is one instance of a whole continent we’ve ceased to marvel at.

There is a commercial version of Cézanne’s work and we call it advertising. Like Cézanne’s work, advertising throws the best things about objects into relief and tells us in insistent and urgently enthusiastic and sensitive ways what is lovable about bits of the world. Advertising is skilled, for example, at pointing out the lovable things in the new top of the range BMW, the cylinders, the leather seat surrounds, the moulding around the wheel arches (lithe and muscular) and of course the army of lights, skilfully massing their beams ready to attack the darkness on the road ahead.

The only problem with advertising is that it isn’t done for enough things, or indeed the things that would be most helpful and convenient for us to appreciate. People who attack advertising get it slightly wrong: the problem is not that we love BMWs, but that so much of our love and awe has been syphoned in that direction and hasn’t been properly excited in other, more realistic areas.

We need an advertising pursued with the same sense of drama and intensity and ambition but directed towards biros, puddles and olives. The reason this doesn’t happen isn’t sinister or profound. It’s just we haven’t yet found a way to pay the enormous sums required to glamorise objects through advertising in the case of lower-priced items.

He needs a campaign for himself

Our reluctance to be excited by inexpensive things isn’t a fixed debility of human nature. It’s just a current cultural misfortune. We all naturally used to know the solution as children. The ingredients of the solution are intrinsically familiar. We get hints of what should happen in the art gallery and in front of adverts. We need to rethink our relationship to prices. The price of something is principally determined by what it cost to make, not how much human value is potentially to be derived from it. We have been looking at prices in the wrong way: we have fetishised them as tokens of intrinsic value, we have allowed them to set how much excitement we are allowed to have in given areas, how much joy is to be mined in particular places. But prices were never meant to be like this: we are breathing too much life into them, and therefore dulling too many of our responses to the inexpensive world.

There are two ways to get richer: one is to make more money; and the second is to discover that more of the things we could love are already to hand (thanks to the miracles of the Industrial Revolution). We are, astonishingly, already a good deal richer than we are encouraged to think we are.

6. Learning to Shop

It sounds very strange to suggest that we might need to learn how to shop. We know we have to learn how to make money, but spending it is overwhelmingly understood to be the straightforward bit. The only conceivable problem is not having enough to spend.

Yet when we’re out to buy a present for someone else, we can often see that we don’t quite know what would really please them. We wisely acknowledge that shopping for others is hugely tricky, but we don’t extend the same generous – and ultimately productive – recognition to shopping for ourselves.

Yet a host of obstacles frequently prevents us from deploying our capital as accurately and fruitfully as we should – a serious matter, given just how much of our lives we sacrifice in the name of making money in the first place.

For a start, far more than we normally recognise, we’re guided by group instincts – which can tug us far from our own native inclinations. A major defence of capitalism has been the impressive notion that it provides us with unrivaled consumer choice and it can indeed seem as if the system actively caters to every possible nuance of taste. Yet while seeming to provide for an apparently inexhaustible individuality, surprisingly standardised consumer patterns in fact dominate the economy.

Day to day, it feels like we are wholly in charge of our consumer decisions – but when we look back in history, we can see how strangely impersonal shopping choices really are. Our desires may feel intensely our own, yet they seem social creations first and foremost.

How else to explain why in the 1950’s, so many people arrived – apparently by their own free will – at the feeling that orange was a properly appropriate colour for a sofa?

Or why in the 1960’s many otherwise very sober people spontaneously (yet simultaneously) discovered they were keen on tail fins on their cars.

Or why in the 1970’s, almost everyone in the world was struck by the urge to buy shirts with very large collars.

The choices may well have suited many, but it is impossible not to believe that at least a few of those who shopped woke up from the age of wide shirt collars or orange sofas with a puzzled sense that they had been induced to want things which had precious little to do who they were.

And yet at the same time, the fear of being thought strange prevents us from taking less socially-endorsed desires more seriously. We might, in our hearts, love to wear a pair of wallabee shoes.

And we might – if left entirely to our own devices – not want to follow every customary detail in the script of how to arrange a holiday, celebrate a child’s birthday or prepare a dinner party, but we may be as shy here as we are with certain of our sexual desires. We are taught to think of ourselves as highly focused on our own pleasures, but most of our trouble stems from a quite opposite problem: just how tentative we are about taking our own feelings at all seriously.

It seems we are so much more distinctive than consumer society allows. It isn’t – as a certain political fantasies suppose – that our tastes are in reality truly simple, more that they are a hugely varied and anomalous. We might be deep into middle age before we finally abandon the dominant story of what we’re meant to wear, eat, admire or ignore.

Part of the problem is that we lack the ability to know, looking back over experiences, what truly brought us pleasure. Our brains aren’t so keen on taking apart their satisfactions – and therefore plotting how to recreate them. If one asks a seven year old why they like a favourite TV programme, they will most likely find the question irritating. They just like it overall, they say. The idea of going into detail and realising that they find the relationship between the main character and their dog inspiring but the urban setting less appealing is very alien. We’re not natural critical dissectors of our own experience. It takes a long, arduous process of training before someone becomes an incisive literary critic or gets good at analysing their own reactions to a work of art. These moves force the mind to do an unnatural thing. And so, correspondingly, it feels strange and difficult to comb through the details of a holiday or a party or a relationship with a jacket or computer in a rigorous search for the pleasurable or painful elements which should ideally guide our expenditure going forward.

Our problems are compounded by the way that reviews are organised. A lot of cultural attention is paid to the business of choosing – but with one curious and significant limitation. It’s assumed we’re accurate in wanting to invest in a particular class of product, we just need help in choosing its best example. Reviews don’t question the overall aptness of looking to get a phone, a car or a hotel at the beach in Southern Spain, they simply guide us to the best among these options. So the position of a single choice within an overall picture of a life falls outside their scope; the more complex trade-offs or opportunity costs aren’t considered. Despite the plethora of reviews, we lack organised, prestigious support for the existential decisions that sit above any single consumer commitment. No wonder we get muddled.

Finally, though the things we buy might truly be lovely, our pleasure is hugely vulnerable to our inner emotional climate. All the advantages of a resort hotel can be destroyed by an argument. Loneliness destroys the charm of any of the clothes we might by. And yet, somehow, the idea of our dependence on emotional factors that lie outside the purchase remains curiously elusive whenever we are at the till.

None of this means that we shouldn’t shop; or expend so much energy on our consumption. Quite the opposite. It isn’t that we are too focused on shopping, we are not thinking deeply and precisely enough about what we’re doing. We haven’t yet learnt to be doggedly precise enough about pinning down our own fun and making sure we get it.

Because it’s so unusual and a little frightening to trust ourselves over the enthusiasms of other people, the process of learning how to shop has to begin with a rather unfamiliar kind of training: with reflection on how we might come to fix upon and isolate the sources of our individual pleasures – even when these may be very fugitive and lacking in any external validation. We may, for example, need to ask ourselves with unusual determination what we truly feel in relation to many of the items in our wardrobes and cupboards and slowly extrapolate ideas of what really fits our core identities, which are liable to run counter to many dominant trends. Moreover, we might start to pay more attention to what truly satisfies us; to note that we spent a surprisingly entertaining afternoon walking down an old canal, finding a series of abandoned warehouses and gas storage facilities, which nourished an interest in the history of industrialisation – but also observe how we were discouraged by the way that this activity had no prestige in the eyes of those around us and how on our next holiday, we were led – like a leaf in a powerful current – to go to Rome, where the guide book directed us to a succession of churches, which we found rather boring (if we were honest, which it’s very hard to be). It should be no insult to admit that the pursuit of happiness through consumption is by nature neither especially individual or easy.

Isaac Davis, the hero of Woody Allen’s Manhattan (1979) has fallen into depression following the failure of a relationship. Much of what previously held interest for him now seems colourless. He walks the streets of New York in melancholy dejection. Then one day, Isaac lies down on his sofa and undertakes a piece of philosophical meditation to try to discover what deep down may still really matter:

Why is life worth living? That’s a very good question. Well, there are certain things I guess that make it worthwhile. Like what? Okay, for me, I would say, Groucho Marx, to name one thing and Willie Mays, and the second movement of the Jupiter Symphony, and Louis Armstrong’s recording of “Potato Head Blues,” Swedish movies, naturally, “Sentimental Education” by Flaubert, Marlon Brando, Frank Sinatra, those incredible apples and pears by Cézanne, the crabs at Sam Wo’s…

Why is life worth living? The crabs at Sam Wo’s. Woody Allen in Manhattan (1979)

The list stands out for its variety, its originality and its personal flavour. There are some luxuries, some very simple things, some elements that have high prestige, others would be thought trivial by the serious – and then there are the crabs from a brightly-lit functional Chinese restaurant in Chinatown. All of us are likely to have a list a little like this, though different in all its particulars – and it’s also liable to be a list which we don’t honour too much day-to-day because it departs from the standard script of what one is meant to like. We may have fewer meals than we would wish in our beloved Chinese diner. We let ourselves be pulled to the latest blockbuster film; the majority of what we listen to is high in the charts.

A more educated consumer base would not necessarily mean a more frugal one. We might discover that many of the things we own bring us very little pleasure at all, but that a few – expensive or cheap – really do make a difference and might henceforth become more focused targets of appreciation and expenditure. We might depart from the big trends in a range of areas, while delighting in them all the more in others. We’d let our subjective enthusiasms direct us to extreme simplicity in some categories and perhaps unbridled extravagance in others. Our spending patterns would overall grow helpfully weirder.

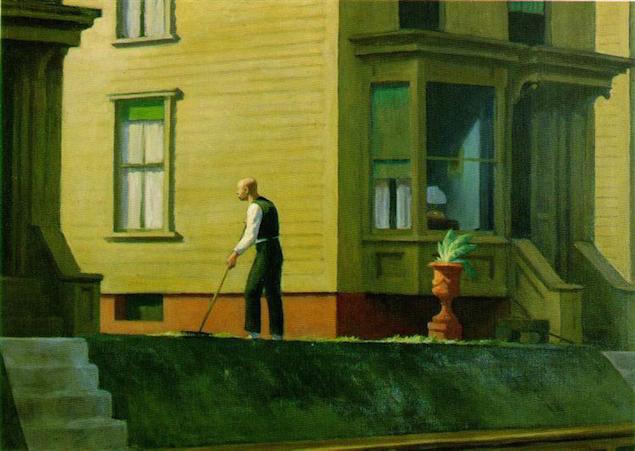

Staying loyal to ourselves may mean having to be disloyal to rather a lot of what is prestigious. The successful innovators, be they in art or business, are those who can remain true to insights that would have seemed – when first made – to be very close to bizarre. Edward Hopper could not have been the first person to feel the lonely charm of the railway station or the strangely comforting anonymity of the late-night diner or the eeriness of Sunday in the suburbs. But those who came before him had too swiftly abandoned their sensations because these had no support from society at large. The figure we call the artist or entrepreneur is – among other accomplishments – someone who minds far less than others about being thought somewhat weird as they go about rescuing and building upon some of their lesser-known yet profoundly significant sensations. Hopper became a great artist through an acute loyalty to his own perceptions.

Edward Hopper, Pennsylvania Coal Town (1947)

For most of the history of modern architecture, the elevator has been one of the least loved and most ‘repressed’ of architectural elements. Lift shafts have been elaborately hidden away, deemed to be inherently uninteresting and not worth drawing our eyes to. And yet occasionally, particularly when we were children, some of us will have had the feeling of being very interested in the hidden bits of lifts, in moments when the doors open and we caught a glimpse down the shaft itself and observed a fascinating echo, an array of cables, pulleys and balancing mechanisms far outstripping in interest anything we might have seen in the rest of the building. The British architect Richard Rogers became a great innovator (and entrepreneur) in part because he knew how to be loyal to these feelings of excitement around technology in general and lifts in particular. Rather than doing the polite and obvious thing, he stayed true to his enthusiasm, remaining confident that many of us might well share it, beneath our surface impassivity. Beginning with the Pompidou Centre (1971), his buildings have always left their shafts exposed, thereby making our journeys between floors moments in which to admire technical ingenuity and feel our spirits rise in contact with the dynamism and intelligence of modern engineering.

Ultimately, we’re imperfect consumers because of a quite basic challenge of the human condition: we’re not very skilled at making ourselves content. It’s a tragic irony that the whole point of consumerism is to please us but that on so many Sunday afternoons, on the way back from a film or a mall, the train station or airport, we may privately acknowledge that we have once again not quite been able to lay our hands on the true nerve centres of pleasure. Consumption is a point at which modern life dramatically intersects with an age-old issue: the origins of human flourishing. At heart, consumer education is a branch of philosophy, a study of how we can educate ourselves as to the true nature, and constituent features of a good life.

****

It isn’t – perhaps – just a coincidence, just an oversight, that we are so bad at appreciating what we have, what is modest and within reach: nature, a quiet moment, our friends…

There is, in our incapacity, likely to be something more active and determined. We are afraid to appreciate what we possess because we associate this acknowledgement with a decline in energy for the hard task of winning more. We are afraid that feeling grateful for what we have to hand will lessen our will to acquire what still eludes us.

But there is in fact no necessary relationship between a growth in appreciation and a decline in effort. Indeed, there is no point in chasing the future until we are better at being more attuned to the modest moments and things that are presently available to us. We don’t face a choice between ambition and appreciation. If we cannot appreciate what we have, there is no point being ambitious for what we as yet lack.