Work • Good Work

Career Therapy

There are few questions harder or lonelier than: ‘what should I do with the rest of my working life?’. We are often simply meant to know the answer – and a lot of people tend to be invested in us continuing along the safe and predictable path.

But, in private, some of us are acutely aware that we aren’t very happy where we are – and would love to find a way towards a job that truly fulfills our souls.

Tantalisingly, many of the answers we need better to direct our futures are inside us already, but we need help in getting them out, in making sense of them and in assembling them into a plan.

This is a set of essays and prompts to help us learn more about our working identities – and to guide us deftly towards the kind of jobs we need in order to thrive and honour our talents.

1. Why Now?

Context

Career ‘crises’ tend to befall us at particular times – for reasons that we don’t necessarily entirely understand but should study with generous attention.

However valid it might be to examine the specifics of our career conundrums, it’s also worth stepping back a little to ask why a dissatisfaction might have descended at this particular juncture.

From a desire to shield ourselves from challenging or anxiety-provoking truths, we might inadvertently be hiding some of the true causes of our mental distress. For example, we might find it easier to say that we hate our job in general rather than admit that we are being dragged down by a frostiness that has descended in our relationship with a particular colleague we had once very much hoped to connect with. A powerful longing to find a new professional identity might – in a circuitous way – be bound up with an unhappiness in our sex lives or a sadness that our children are to leave home soon.

This isn’t to say that there is nothing wrong with our lives, simply to emphasise that we need to get as clear as possible about what exactly the problem(s) might be, so as to ensure that we can accurately focus in on the root causes of our restlessness.

In career therapy sessions, ‘why now?’ is one of the most powerful questions ever raised – and we should keep our minds open to the many varied available answers. We might be in some sort of crisis but – with beautiful strangeness – perhaps not exactly the sort of career crisis we had initially imagined.

Questions:

- What is unique to this moment?

- Is there anything else distinctly challenging that might be unfolding?

- If you could address something in your life other than your career, what might this be?

- What’s changed since you were last professionally content?

Urgency

We often suffer not just from a desire to move jobs, but from a panicked sense that we need to move right now – even when, objectively, there is no immediate financial or practical necessity to do so.

The mind comes to a view that by taking a particular course of action, by ‘doing something now’, we will rid ourselves of what feels like an underlying agony or claustrophobia. We should notice the extent to which we are motivated not by a relaxed curiosity about another professional world, but by a desire to stop an inner suffering and restlessness.

This should give us pause for thought. Career therapy is as a rule suspicious of haste. It isn’t that we never need to make a change. It’s just that the longing to make a change while feeling that one has no alternative but to do so is often a sign that we’re trying to solve a problem by deploying an only partially-related solution. The time to move is when not moving might also – somehow – be an option.

If we can stay patient, we may realise that there is, in the background, an unconscious hope that a career move is going to spare us some kind of emotional toll: an ongoing humiliation, a feeling of not being valued, a sense of helplessness or unlovability. It might be that we need to go back and mourn something that went wrong in the past, rather than alter our job in the present.

Career therapists often operate with a curious rule of thumb: if it looks like a work problem, it may well, deep down, be a love problem. And, correspondingly, if it looks like a love problem, it can – oddly – turn out to be in essence a work problem…

Exercise:

- How do you hope you will feel after this career move?

- How do you think you will feel if you don’t change?

- What would be the dangers of not acting?

- What are the dangers of gradual change?

- Might it be a love problem rather than a work problem?

The Difficulty of Thinking

One of the frustrating features of our minds is that the more significant our thoughts happen to be, the more they have a tendency to escape our grasp. Thinking about our careers is very hard indeed, because it tends to induce intense anxiety about the value of our lives and the scale of the challenges before us.

An original thought might, for example, herald a realisation that we’ve been pursuing the wrong approach to an important issue for far too long. We might discover that there is a lot we’re going to need to change.

A blunt demand that we should ‘think harder’ may not be the best approach. In order to give new, threatening but important thoughts the best possible chance of developing, we may have to make use of certain mental tricks. The mind sometimes doesn’t think too well if thinking is all it is allowed to do; so it should sometimes be a given a routine task to distract it and help it lower its guard. For instance, a long journey alone in a train or on a plane may render our minds more willing to entertain certain intimately challenging ideas. We can find reassurance when we are at a distance from the normal context of our lives; if we make a decision we won’t have to act on it immediately. The passing countryside can give us a spectacle to absorb our restlessness. Something similar might happen if we go alone to a cafe – or take a walk in the countryside: here the rhythm of our steps is semi-automatic, we half notice what’s going on around us – but it’s not important or urgent; the more paranoid, rigid surface of the mind can be gently occupied so that our deeper and more awkward thoughts can slip in unnoticed.

We should accept that our brains are strange, delicate instruments that evade our direct commands and are perplexingly talented at warding off the very ideas that might save us or help us flourish.

Exercise:

- Don’t sit down for hours with a blank sheet of paper titled: ‘What I should do with the rest of my life.’

- Think while trying to do something else, for example, having a shower, taking a train ride, sitting in a cafe

- Keep your thoughts in a notebook: let them tumble out randomly and accumulate them slowly. See, after a few weeks, what you’ve collected. Understanding ourselves tends to happen retrospectively.

- To quell your own mind’s tendency to go blank, plug your brain into someone else’s. Talk this through with a friend – or a therapist.

The Agony of Choice

A lot of the reasons why we don’t move forward is that we are terrified of choice – and because, implicitly, we believe that there might be such a thing as cost-free, perfect choice and, by extension, a flawless life.

To liberate ourselves to move forward, we should accept – with robust courage – the inevitability of pain around choice. The difficulty of choosing can mean that many of us spend our lives avoiding hard choices, which ends up being a kind of choice all of its own. But there is no alternative to picking something and to making our peace with the compromise that every choice entails.

We procrastinate, at times, in a desperate attempt to keep at bay the cruel limitations of reality. If we move city, we might have new work prospects, but we’ll lose our current friends; if we devote ourselves to one specific career, other sides of our character will be neglected… If we delay choosing, all options appear to stay alive, at least as possibilities. Yet that is a grave illusion. We should quell our procrastination by accepting that not choosing is in itself a choice and that every choice will necessarily mean missing out on something important.

We should get better and faster at making decisions, sure in the knowledge that every decision will be in its own way slightly wrong and somewhat sad – while also slightly right and somewhat good.

Exercise:

- What are the upsides of staying put?

- What are the upsides of moving?

- What are the downsides of staying put?

- What are the downsides of moving?

There is no cost-free choice…

2. IMAGINE

Childhood

Many of the best clues as to what we might do in the world of work are to be found in a time when we largely had no thought of work. Childhood provides us with a particularly valuable storehouse of career ideas because it is blessedly free of so many of the elements that later inhibit or distort our true interests. As children, we generally had no thought of status or money – and didn’t even wonder whether we were any good at what we were doing. It just seemed like fun to pretend to be a pilot or a chef, to design a house or to make an advert.

It isn’t exactly what we used to play at as children that counts, it is the pleasures that we found in certain games that needs to be distilled and recovered – and then translated into adult concepts. Once we’ve remembered what we liked to do (build model planes or draw intricate imaginary worlds, organise treasure hunts or capture squirrels), we should make a few patient guesses as to what actually mattered to us in these activities – and see whether there might be echoes or analogous satisfactions to hand somewhere in the adult world.

Children are particularly unanalytical about what they enjoy; but they are also particularly adept at, and passionate about enjoying themselves. We should be sure to engage with a version of ourselves that once knew our pleasures well, perhaps far better than we know them now.

Exercise:

- Draw a table with three columns. In the left hand column, make a list of various things you loved to play at as a child.

- Next to each one, in the middle column, pin down the pleasures that were active within each game or hobby.

- In the right hand column, write down where comparable pleasures might be found in adult occupations.

- If work were more like a game, if status, money and talent didn’t count, what might you do next?

A Future Self

Our imaginations tend to be so daunted by the practicalities required for us to change our lives, we grow inhibited about properly visualising the future that we ostensibly seek. We’re so concerned with the next three moves we might make (and all the challenges involved in, say, a resignation, a return to education etc…), we don’t richly explore what our lives might actually look like if everything worked out as we currently hope.

So we should undertake a thought-exercise in which we leap ahead ten years from now – and picture that our plans have come to fruition. We should evoke for ourselves both the broad outline of our lives and a range of specific details. We should think about what a typical Tuesday afternoon might look like and how it would be to contemplate a new week from the perspective of a Sunday evening.

We might discover a host of complex and accurate pleasures or, surprisingly, a selection of surprising irritants and rather testing compromises.

Dreaming of the future in a frictionless way lends us the energy to look past the hurdles immediately before us – as well as, sometimes, granting us permission to remain exactly where we are.

Exercise:

- Journey forward ten years: everything has worked out according to your current plans. How does your life feel?

- How is an average week filled? What are you doing on a Thursday morning?

- What pleases you?

- What still annoys you?

Success

Surprisingly perhaps, our desire to make a change in our career is frequently driven by having already succeeded well enough in some area or another – but then perhaps grown bored or dissatisfied on discovering that success was not quite what we imagined it might be.

Before we move on too swiftly and pick yet another area to do well in, we should interrogate some of our underlying hopes about what success in any field can bring us.

We are used to framing our career ambitions in relatively practical terms: we speak of wanting money or fame, excitement or intellectual stimulation. But our true wishes can be fascinatingly emotional in nature. We should ask ourselves about the psychological benefits that we hope to secure through succeeding at our newest ambition. Our answers may feel strikingly odd, almost naive or in some way quite disconnected from the job we’re ostensibly trying to master. We might say that, if we succeed, we hope we will: ‘finally be loved’, ‘No longer have to worry’ or ‘be able to make it up to everyone.’

Success is hard enough to secure: we should ensure that, if it were one day to be ours, it would truly offer us what we crave.

Exercise:

- Without thinking too much, complete the sentence: If I succeed, I will finally be able to…

- If my career goes as I want it to, I won’t have to…

- What has success to date not quite brought me?

- What would it be perplexing or sad if future success couldn’t deliver?

After the Lottery

We operate in societies where the vast majority of people tell themselves that they work for one reason and one reason only: money. This may sometimes be true, but it’s rare for anyone to work for cash alone – and the sensible-sounding nature of this motive tends to mask a variety of other more fascinating and emotional motives we harbour for making it to work every day.

Before making any radical moves, we should ask ourselves what we might do if we won the proverbial lottery.

The question can evoke how much we lean on work for more than merely financial support. We do so, perhaps, to stave off anxieties about our legitimacy or ward off our fears of loneliness or worthlessness. Work might be compensating for intractable difficulties in our relationships or lending us opportunities to feel wanted and important. We might be trying, all the while, to repair a broken bond with our a long-dead father or to impress an indifferent and narcissistic mother.

None of these ambitions are illegitimate. It’s just that by insisting too much that we are just financially-maximising creatures and are going to work because we ‘need to’, we miss out on understanding the complex psychological pleasures and compulsions that come from engaging with work – and we are therefore often not as accurate as we might be when choosing what task to devote ourselves to next.

Exercise:

- List five reasons why you work.

- Rank them in order of importance

- What would you do after the lottery win? How does this differ from what you’re doing now?

- What do you need work for other than money?

3. BLOCKS

The Duty Trap

Every education system rewards duty and tends to encourage us to forget our true desires. After years of school and university, we often can’t conceive of asking ourselves too vigorously what we might in our hearts want to do with our lives; what it might be fun to do with the years that remain. It’s not the way we’ve learnt to think. The rule of duty has been the governing ideology for 80% of our time on earth – and it’s become our second nature. We are convinced that a good job is meant to be substantially dull, irksome and annoying. Why else would someone pay us to do it?

This dutiful way of thinking has high prestige, because it sounds like a road to safety in a competitive and alarmingly expensive world. But, in fact, success in the modern economy will generally only go to those who can bring extraordinary dedication and imagination to their labours – and this is only possible when one is, to a large extent, having fun. Work produced merely out of duty is limp and lacking next to that done out of love. In other words, pleasure isn’t the opposite of work; it’s a key ingredient of successful work.

Yet we have to recognise that asking ourselves what we might really want to do – without any immediate or primary consideration for money or reputation – goes against our every, educationally-embedded assumption about what could possibly keep us safe – and is therefore rather scary. It takes immense insight and maturity to remember that we will best serve others – and can make our own greatest contribution to society – when we bring the most imaginative and most authentically personal sides of our nature into our work. Duty can guarantee us a basic income. Only sincere, pleasure-led work can generate sizeable success.

Exercise:

- Who taught you about duty?

- Did following duty work for them?

- Think of those you most admire: in what ways did they not follow duty?

- What would be the satisfying but un-dutiful thing for you to do?

Good Boys & Girls

Many of us are good boys or girls. When we were little, we did our homework on time. We kept our rooms tidy. We wanted to help our parents. People imagine that good children are fine; because they do everything that’s expected of them. And that, of course, is precisely the problem. The secret sorrows – and future difficulties – of the good boy or girl begin with their inner need for excessive compliance. The good child isn’t good because by a quirk of nature they simply have no inclination to be anything else. They are good because they have no other option. Their goodness is a necessity rather than a choice.

Many good children are good out of love of a depressed harassed parent who makes it clear they just couldn’t cope with any more complications or difficulties. Or maybe they are very good to soothe a violently angry parent who could become catastrophically frightening at any sign of less than perfect conduct. But this repression of more challenging emotions, though it produces short-term pleasant obedience, stores up a huge amount of difficulty in later life.

Following the rules won’t get you far enough. Almost everything that’s interesting, worth doing or important will meet with a degree of opposition. A good child is condemned to career mediocrity and sterile people-pleasing.

The desire to be good is one of the loveliest things in the world, but in order to have a genuinely good life, we may sometimes need to be (by the standards of the good child) fruitfully and bravely bad.

Exercise:

- How did you grow up ‘good’?

- What has being ‘good’ made you miss out on?

- What would be the interestingly rebellious thing you might do?

- What was the good child in you made to feel scared of?

The Impostor Syndrome

In many challenges – personal and professional – we are held back by the crippling thought that people like us could not not possibly triumph given what we know of ourselves: how reliably stupid, anxious, gauche, crude, vulgar and dull we really are. We leave the possibility of success to others, because we don’t seem to ourselves to be anything like the sort of people we see lauded around us.

The root cause of the impostor syndrome is a hugely unhelpful picture of what other people are really like. We feel like impostors not because we are uniquely flawed, but because we fail to imagine how deeply flawed everyone else must necessarily also be beneath a more or less polished surface.

The impostor syndrome has its roots in a basic feature of the human condition. We know ourselves from the inside, but others only from the outside. We’re constantly aware of all our anxieties, doubts and idiocies from within. Yet all we know of others is what they happen to do and tell us, a far narrower, and more edited source of information.

The solution to the impostor syndrome lies in making a crucial leap of faith: that everyone must (despite a lack of reliable evidence) be as anxious, uncertain and wayward as we are. The leap means that whenever we encounter a stranger we’re not really encountering a stranger, we’re in fact encountering someone who is – in spite of the surface evidence to the contrary – in basic ways very much like us – and that therefore nothing fundamental stands between us and the possibility of responsibility, success and fulfilment.

Exercise:

- Imagine some of the most intimidating, accomplished and impressive people you know on the toilet. Reflect on Montaigne’s remark: ‘Kings and philosophers shit; and so do ladies.’ And, he might have added, so do top CEOs, entrepreneurs and creatives.

- Imagine that others feel all the fears you do; they are just hiding them. As you hide yours.

- Stop waiting to be given permission.

- No one really knows; you have as good a chance as any one…

Envy

One of the best guides to working out what to do with our lives is also one of our most shameful and taboo emotions: envy. While envy is uncomfortable, squaring up to the emotion is an indispensable requirement for determining a career path; envy is a call to action that should be heeded, containing garbled messages sent by confused but important parts of our personalities about what we long to do next.

Without regular envious attacks, we couldn’t know what we wanted to be. Instead of trying to repress our envy, we should make every effort to study it. Each person we envy possesses a piece of the jigsaw puzzle depicting our possible future. There is a portrait of a ‘true self’ waiting to be assembled out of the envious hints we receive when we turn the pages of a newspaper or hear updates on the radio about the career moves of old schoolmates. Rather than run from the emotion, we should calmly ask one essential and redemptive question of all those we envy: ‘What could I learn about here?’

Even when we do attend to our envy, we generally remain extremely poor students of envy’s wisdom. We start to envy certain individuals in their entirety, when in fact, if we took a moment to analyse their lives we would realise that it was only a small part of what they had done that really resonates with us, and should guide our own next steps. What we’re in danger of forgetting is that the qualities we admire don’t just belong to one specific, attractive life. They can be pursued in lesser, weaker (but still real) doses in countless other places, opening up the possibility of creating more manageable and more realistic versions of the lives we desire.

Exercise

- Keep a note of everyone you envy.

- Imagine that it isn’t their whole life you envy, just a part: beside each name, write down adjectives you envy.

- How might some of the qualities you envy be found in your future life without having exactly their life?

4. LETTING GO

Processing the past

One thing that’s liable to get missed when we move job is the tricky truth that we ultimately had to change course because, in one way or another, something went wrong. Perhaps we misjudged what our real ambitions were; we failed to get on with colleagues; we fell foul of office politics, we realised that our temperament wasn’t welcome… Something sad and bad brought us to alter the course of our lives.

Amidst the excitement of change, we tend to forget the uncomfortable past and focus instead on the next job – and all that it can bring us. But, in the process, we are in danger of missing out on valuable information – and of not sufficiently sifting through the unhappy evidence thrown up by our recent experiences. We need to take time to ponder our setbacks or dead ends. We can’t reliably build a happy future without understanding in detail what didn’t work out until now. There are important truths about ourselves and our weaker or more complicated sides lurking within the story of our old job. It isn’t inevitably someone else’s fault. It wasn’t just a rubbish company. It’s too simple to say we ‘simply wanted a change’. All these sound like attempts to bypass a vital confrontation with regret, ambivalence and mishap.

We should allow ourselves to be self-reflexive, frustrated and a little sad. There was probably some kind of anger that helped to drive us to make a change – and this needs to be given a proper airing. Without some form of emotional processing, we may get mildly depressed, as we do whenever something painful or cross hasn’t been properly understood and felt.

We have to ensure we have properly dissected and mourned the past before we have any right to be confident about our future plans.

Exercise:

- What were your initial hopes of your last job?

- How did the last job disappoint you?

- If there’s anger somewhere in your feelings, what are you angry about?

- How did others let you down?

- How did you let you down?

- What would you – with the benefit of hindsight – have done differently?

Permission

When we were small, we needed permission to do pretty much anything at all – and the move was sensible. Others knew better than we did what was safe, what was socially acceptable, what would work, what was in line with our needs…

But, for too many of us, this sensible childhood dynamic continues deep into the adult world, where it no longer serves any real purpose. We often know exactly what job we’d like to do next and are right in our hunches; and yet we remain stuck because we need someone else to give us permission to make the move that would render us happy.

Our block provides an occasion to reflect on an inhibition that must follow us through a number of situations in our lives. Somehow we are lacking trust, not in our abilities or our enthusiasms, but in our right to make big positive decisions (perhaps about who to marry, how long to stay with a partner, where to live or how to work…). Instead, we naturally assume that there is someone out there, a parent or parental figure, who first has to wave us through or, alternatively, can say a definitive ‘No’.

It’s often with such feelings in mind that people finally visit a career therapist; they don’t want advice, they simply (and just as importantly) crave permission.

We should, going forward, learn to give ourselves this permission by ourselves, understanding how little trust was (probably) once placed in us in childhood by big people who called the shots. We should mourn the lack of agency we were bequeathed with by the past – and take active steps to compensate for this vulnerability in the present.

We still need permission, of course, but it’s a permission that can handily be sought from one person who counts above all else and is always to hand: ourselves.

Exercise:

Place two chairs facing each other. Sit down in one of the chairs, facing the empty chair and imagine someone kind and caring and worldly sitting in the chair opposite you:

- Tell them your hopes and fears, your wishes and your tribulations about moving on.

- Then go and sit in the empty chair and face your old chair and imagine speaking to you.

- Now tell the chair opposite (you) that you have heard, that you understand and that you give them permission to act on their desires.

- Reflect on the exercise; note in particular how you already have a ‘voice’ inside you that can give you permission in a kindly way. You just aren’t used to seeking it out and listening to it. Do so from now on, whenever key decisions arise… Imagine a life in which you could more often, and more generously, give yourself permission by yourself.

Self-affirmation

When we are in career difficulties, it is easy to get ever more gloomy about our situation: we have failed, we lack talent, we don’t have the required imagination or insight…

Most of us have advanced degrees in self-destruction and self-suspicion. We may think that this gives us access to important truths about who we ‘really’ are. But, in reality, hating oneself is no guide to any sort of truth and is merely a route to missed opportunities.

It is, of course, important to acknowledge our setbacks and our weaknesses, but never at the expense of caring for ourselves and appropriately celebrating what we’re good at and can take pride in. After periods of critical introspection, there comes a moment when we need to shift course and accentuate the positives, to illustrate to ourselves how much we still have to offer. We should stop fearing that rejoicing at being us is always hubristic, arrogant or deluded. We should stop anticipating punishment if we get too overjoyed or somehow fear that if we get one thing, something else might be taken away.

We should be aware of our tendency to say ‘yes, but’… and of how, when we want to take pride in an achievement, a cruel ‘but’ so often comes along to spoil our mood. ‘I’m so happy I got this promotion, but it was sheer luck really’. ‘I’m great at this job, but they must have hired me only because they knew about my dad…’

We need to learn a very surprising lesson: that we are – despite a lot that we might have taken on board in childhood – in certain areas, genuinely rather wonderful.

Exercise:

- For once, make the case for you. What are you rather brilliant or good at? What has gone well in your career?

- Write down the top three achievements you feel really proud of, however large or small these may be.

- Imagine you were a good friend of yours: how would you sell ‘you’ to a prospective employer?

- Learn to be a bit more suspicious of your innate modesty. Finish the sentence: If I wasn’t so modest, I might…

The Status Quo

We live in a world that doesn’t think very highly of people who don’t move on. Career metaphors tend to have radical mobility built into them; it’s all about paths and ladders, new horizons and bold trajectories.

This is often an extremely helpful stance (lending us courage and countering inbuilt timidity) but it can have an obtuseness of its own. There are situations when we may experience a genuine sense that we are not in the right job, and come to the view that moving on is the only option. We may share our intent with friends and colleagues, we may go into therapy, we may start to plan for a radical change for the rest of our lives and receive adulation from those around us for our courage and energy.

And then we may come to a rather embarrassing realisation; that having considered our options, our character, the real nature of our dissatisfaction and the impulses that drive us on, we’d rather stay put; we’re OK where we are. We don’t want to move at all. But, of course, by now, this can seem extremely shameful, the coward’s way out.

Far from it; we should accord as much prestige to a conscious decision to stay put as we do to a considered impulse to go elsewhere. There should be no shame in either direction.

Maybe our current position feels like a quiet resting place – but quiet resting places are fine. Maybe we’ll never get to the top but the middle has its legitimate attractions. Good modest lives are an achievement in themselves. We should be as suspicious of being prevented by others from doing something we want – as we are of being encouraged into roles that don’t – on reflection – suit us.

The status quo is not the enemy, it’s simply another option and often a very dignified and decent one at that.

Exercise:

- Who would you be afraid of disappointing if you stayed put?

- Who might be mean or judgemental towards you if you had a quiet life?

- Where is the pressure to accelerate, increase, break barriers and rise to the next level coming from? Do you – on reflection – agree with it?

- One side of you should now tell the other why a quiet life is – in fact – a hugely noble and valuable option. In case you were wondering…

5. WHAT’S NEXT?

Evolution

Some of the reason we find it hard to move forward in our careers is that we imagine change in overly dramatic terms. Either we stay put – or we have to sell the house, go back to university for five years, lose all our friends and sacrifice all our leisure hours…

When the opposition is so stark, no wonder we end up stuck, often against our will. A more helpful approach is to think of big changes happening via very small steps and very gradual alterations: that is, in terms of evolution rather than revolution. People might not even notice what was going on. It might just mean taking one evening class on a Tuesday or volunteering for something on the weekend. An eventual enormous shift might be set in motion by nothing more outwardly dramatic than buying a book or meeting one or two people for a coffee. Minor moves can strengthen our courage by giving us insight in an area where we as yet have very little experience. They break through the unhelpful but widely prevalent sense that we should either remain as we are or change everything. Oddly, there is a far less glamorous, more neglected third option we can explore: the careful evolutionary step.

Exercise:

- Identify five things, very small things, you could do that won’t upend your life but would nevertheless be the first steps towards a new career.

- What could you change inside your current job to help you in some way prepare for a next job?

- How could you fill two hours of your leisure time with something that helped to move you in the right direction?

- Imagine giving yourself a whole year to do nothing but ‘small steps’ towards a Big Goal.

Unfixation

When we plan for a new career, we often get unhelpfully fixated on one kind of job that we feel we need above all others. We set our sights on becoming an architect or a journalist, a graphic designer or an entrepreneur, an actor or a novelist… Our choices tend to reflect popular ideals of a ‘good job’ and are, for this reason, often heavily oversubscribed or deeply insecure.

The solution to such fixations lies in coming to understand more closely what we are really interested in beneath the headline of our desired job, because the more accurately and precisely we fathom what we really care about, the more we stand to discover that our interests actually exist in a far broader range of occupations than we have until now been used to entertaining.

When we properly grasp what draws us to one job, we often identify qualities that are available in other kinds of adjacent employment as well. What we really love isn’t this specific job, but a range of qualities we have first located there, normally because this job was the most conspicuous example of a repository of them. Yet, in reality, the qualities can’t only exist there.

This is not an exercise in getting us to give up on what we really want. The liberating move is to see that what we want exists in places beyond those we had identified – and in perhaps rather easier or safer roles as well.

Exercise:

- Write down a list of your chosen ‘ideal’ jobs.

- Now redescribe them in terms of their imagined pleasures (ie. creativity, self-expression, prestige… etc.)

- Try to imagine that these pleasures could, and must, exist in other occupations: what might these be?

- How could you find some of what you want in a job that is hard to secure in one that isn’t?

Family Templates

For most of human history, the working destiny of every new generation was automatically determined by the preceding generation. One would become a farmer or soldier like one’s father or a seamstress or teacher like one’s mother. Nowadays, on the surface at least, everyone is free to choose to do whatever they like. Families aren’t meant to interfere – and most don’t. Not overtly at least.

Nevertheless, a lot of our inhibitions around our career moves can be traced back to the subterranean influence of parental models. Beneath the surface, we are guided by an unconscious awareness of what would please those whom we love and still want – perhaps despite everything – to impress and delight.

Many parents would never dare to say ‘no’ to a move we’d make. But we can fear a subtle withdrawal of love just as much. We sense our parents’ wishes and excitements and, because we love them, try to align ourselves with them. It’s very natural. But it may be tragically at odds with doing the kind of work that could actually bring us fulfilment.

We should take courage from the fact that very many families are, for a short time, upset by children’s career choices. But almost no families ever stop loving their children on account of what job they do. At worst, you’ll be facing a short interval of frostiness, not the excommunication your childhood self may deep down fear.

Exercise:

- If I changed my job, I might displease my…

- If I stayed put, I might displease…

- In a life lived according to my parent’s wishes, I would probably…

- Imagine that it might be possible both to upset one’s parents a bit – and fundamentally retain their love.

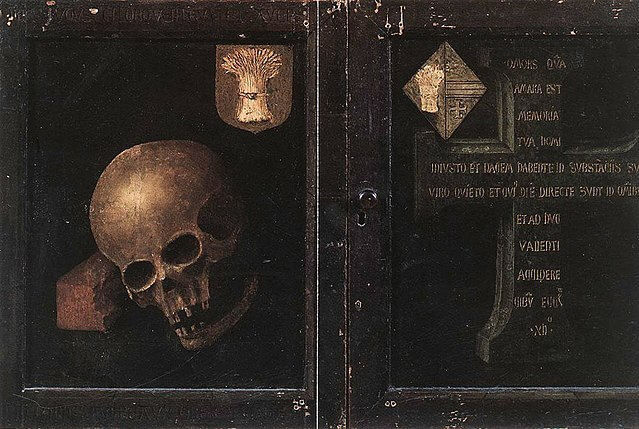

Death Thinking

Career change is frightening. So as to gain confidence, we should more often dwell on something even scarier: how soon we will be dead. Next to this ghastly idea, the slight discomfort of moving jobs or of retraining will – redemptively – be revealed as essentially trivial and easily mastered.

We’re often behaving as if we were immortal. Why else would we fail again and again to square up to what we need to do? We are not terrified enough for our own good. We are behaving like gods or superhuman entities who have centuries to get it right.

To overcome our tendencies to delay and evade, we need to bring the pressure of another – and even greater – fear to the situation. We need to scare ourselves of something very large in order to liberate ourselves to think with greater energy about the myriad of immediate challenges before us.

Death should also liberate us somewhat not to mind too much if we do hit obstacles in more ambitious ventures, for if everything is in any case doomed to end in the grave, then it might not matter overly if we fail wholeheartedly. The thought of death may be at once terrifying and the harbinger of a distinct kind of light-heartedness and requisite irresponsibility.

Exercise:

- Calculate how many more years you may have to live in relation to an average life span in your part of the world. Frighten yourself by cutting off 20 years for cancer or a heart attack (the two great killers).

- Could you imagine that if you had one year you’d want to spend a lot of it working? What would your job need to be like to make you feel that way?

- What kind of jobs open to you continue to look noble and serious in relation to death?

- What achievements would you like to be remembered for?