Leisure • Self-Knowledge • Psychotherapy

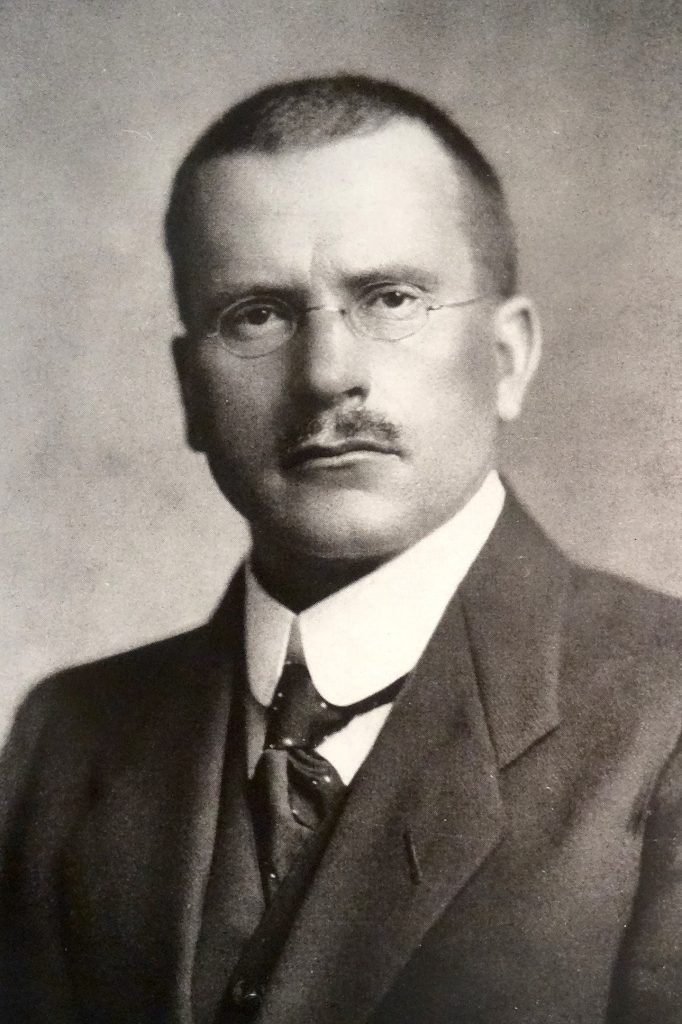

Carl Jung’s Word Association Test

One of the most significant discoveries of the early 20th century was of a part of the mind we now refer to as ‘the unconscious.’ It came to be properly appreciated that what we know of ourselves in ordinary consciousness comprises only a fraction of what is actually at play within us; and that a lot of what we really want, feel and are is not at our mental fingertips, lying instead in a penumbra of ignorance, fantasy and denial which we can only hope to dispel with patient and compassionate efforts, probably with the assistance of an analyst.

Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams, first published in Vienna in 1900, was the landmark study of the workings of this unconscious region, and detailed the mind’s relentless attempts to hide a great many of its most salient truths from itself in the form of dreams — which might shock, disturb or excite us while they unfolded but would then be deliberately forgotten or misunderstood upon our waking.

At much the same time, 700 kilometres to the west, over the border in Switzerland, another pioneering figure in early psychoanalysis, Carl Jung, took a complimentary but more direct and arguably more robust approach. Still only in his late twenties, Jung held a prominent position in Zurich’s foremost psychiatric institution, the Burghölzli clinic and had understood that many of his patients were suffering from symptoms created by a conflict between what they deep down knew of themselves and what their conscious minds could bear to take on board about their feelings and desires. Someone might, for example, lose all ability to speak because of one or two things they so longed, but were so afraid, of communicating to particular people. Another might develop a terror of urinating because of a humiliation that they had suffered in childhood but that they lacked the wherewithal to remember and process. Following Freud, Jung believed that healing and growth required that we learn to untangle our mental knots and more fully appreciate our complicated, sometimes surprising yet real identities.

Freud had concentrated on interpreting his patient’s night-time visions and in listening to them speaking at length in unhampered ways on his therapeutic couch. Jung felt this took too much time and was too much at the mercy of the right chemistry between analyst and patient. Together with his colleague Franz Riklin, in 1904, he therefore developed what he took to be a more reliable technique which he termed the Word Association Test. In this, doctor and patient were to sit facing one another and the doctor would read out a list of one hundred words. On hearing each of these, the patient was to say the first thing that came into their head. It was vital for the success of the test that the patient try never to delay speaking and that they be strive to be extremely honest in reporting what they were thinking of, however embarrassing, strange or random it might seem.

Jung and his colleague quickly realised that they had hit upon an extremely simple yet highly effective method for revealing parts of the mind that were normally relegated to the unconscious. Patients who, in ordinary conversation, would make no allusions to certain topics or concerns, would — in a word association session — quickly let slip critical aspects of their true selves.

Jung grew interested in how long his patients paused after certain word prompts. Despite the request that they answer quickly, in relation to certain words, patients tended to grow tongue tied, unable to find anything they could say and then protesting that the test was silly or cruel. Jung did not see this as coincidental. It was precisely where there were the longest silences that the deepest conflicts and neuroses lay. A literal tussle could be observed between an unconscious that urgently wanted to say something and a conscious overseer that equally urgently wanted to stay very quiet indeed.

In a given test, the doctor might say ‘angry’ and the patient might respond ‘mother.’ They would say ‘box’ and the patient might respond ‘my life shut in one.’ They might say ‘lie’ and the patient would respond ‘brother.’ And they might say ‘money’ and the patient, struggling with guilt and shame, might go silent for a very long time before saying they needed to get some air.

Jung and Riklin published their research in a book called Diagnostic Association Studies. Written in dense scientific jargon, it comprises a succession of charts about what people answered in how long according to their ages, classes, genders and occupations. We are — unfortunately — unlikely to learn very much from the book today, but the interest of the underlying test lies less in the specific purpose for which Jung used it than in what it can more broadly suggest to us about ourselves when we turn to it in more intimate ways.

Though it was made for a clinician to interpret, we may gain a huge amount from sitting the test on our own and analysing our responses and hesitations according to what we know of who we are. We may be ambivalent about self-knowledge but we are ultimately also in a pole position to make advances; in our more honest moments, we know rather a lot about where the bodies are buried.

We can use Jung’s hundred words as a provocative guide to regions of our experience that we have to date lacked the courage to explore — but that might hold the key to our future development and flourishing. And, of course, where we go blank and decide the test is really very silly, there we should pay the greatest attention.

| 1. head 2. green 3. water 4. to sing 5. dead 6. long 7. ship 8. to pay 9. window 10. friendly 11. to cook 12. to ask 13. cold 14. stem 15. to dance 16. village 17. lake 18. sick 19. pride 20. to cook 21. ink 22. angry 23. needle 24. to swim 25. voyage 26. blue 27. lamp 28. to sin 29. bread 30. rich 31. tree 32. to prick 33. pity 34. yellow 35. mountain 36. to die 37. salt 38. new 39. custom 40. to pray 41. money 42. foolish 43. pamphlet 44. despise 45. finger 46. expensive 47. bird 48. to fall 49. book 50. unjust | 51 frog 52. to part 53. hunger 54. white 55. child 56. to take care 57. lead pencil 58. sad 59. plum 60. to marry 61. house 62. dear 63. glass 64. to quarrel 65. fur 66. big 67. carrot 68. to paint 69. part 70. old 71. flower 72. to beat 73. box 74. wild 75. family 76. to wash 77. cow 78. friend 79. luck 80. lie 81. deportment 82. narrow 83. brother 84. to fear 85. stork 86. false 87. anxiety 88. to kiss 89. bride 90. pure 91. door 92. to choose 93. hay 94. contented 95. ridicule 96. to sleep 97. month 98. nice 99. woman 100. to abuse |