Leisure • Literature

Charles Dickens’s Secret

Almost no other writer has ever been quite as successful — whether critically or commercially — as Charles Dickens. He was, by quite some distance, the bestselling author of the Victorian era: beloved by millions of readers throughout the world (including Queen Victoria herself). His novels — Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol — have never been out of print: inspiring countless film, theatre and TV adaptations and occupying a central place in the canon of Western literature. He has even bequeathed us an adjective — ‘Dickensian’ — to rival Victoria’s own as a descriptor of his age.

But Dickens spent most of his life hiding a terrible secret — one that helps to shed light on his peculiar genius…

Born in Portsmouth in 1812, Charles Dickens was the second of eight children. His father, John Dickens, worked as a clerk for the Navy, keeping records and accounts of officers’ wages. It was a respectable enough career — if not one that came with a particularly high salary. But John was determined to give his wife and children the life he felt they deserved.

The Dickenses moved to London, and later to Chatham, in Kent, where they lived in a fashionable, three-storey terraced house near the centre of town. They kept a housemaid and a cook; the children attended private schools. In short, they seemed the very model of a ‘genteel’, middle-class family.

Charles, the eldest son, was a credit to his parents. He did well at school, read voraciously — his favourite books included Robinson Crusoe and Arabian Nights — and tried his hand at writing a few early, Arabian Nights-inspired stories. He was a born entertainer: fond of climbing on tables at their local tavern to regale the patrons with comic songs. He had dreams of becoming a famous actor…or possibly a clown.

His father encouraged his lofty ambitions. After he overheard Charles admiring the grand country house they would often pass on walks in the Kentish countryside, he promised his son he would one day own it — “so long as you work hard enough”.

But when Charles was twelve, his life came crashing down all around him. The comfortable, cosseted existence his family were living had been built on sand. It gradually emerged that his father had secretly been taking out enormous loans to fund their ever-improving lifestyle. He owed money all over town — and the bills were coming due.

In an effort to escape his creditors, he moved the family back to the relative anonymity of London. They were forced to sell nearly all their possessions — including the furniture and silverware. But in 1824, the bailiffs finally tracked them down. John Dickens was arrested, tried, and thrown into prison for debt.

In those days, merely to be in debt was considered a criminal offence. It was a patently nonsensical law; leaving those imprisoned for debt without any means of repaying what they owed. But such was the warped, vindictive logic on which English society was based.

John Dickens was locked up in the Marshalsea, a dark, forbidding prison on the banks of the River Thames. The rest of the family — including Charles’s mother and four younger siblings — moved into the prison with him. All except Charles himself…

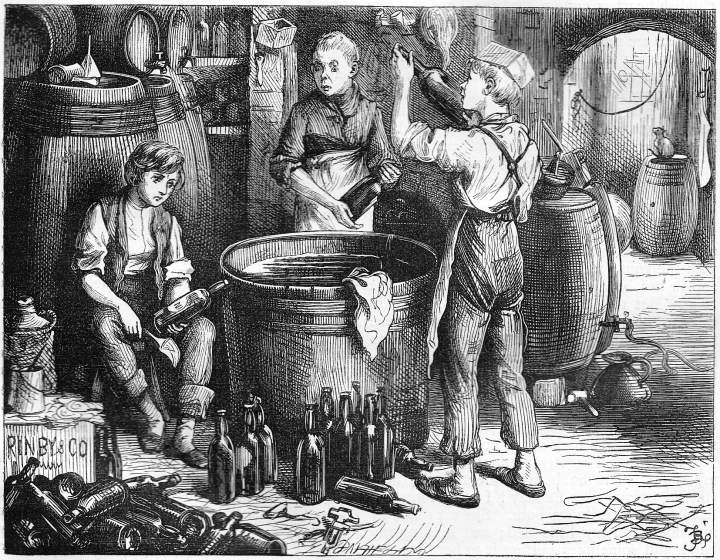

For overnight, the twelve year old Charles had become the family’s only source of income. He was pulled out of school and sent to lodge with an eccentric relative who ran a dilapidated boarding house in Camden. To cover his rent — and contribute to paying off his father’s debts — another relative found him a job: working in boot-blacking factory, Warren’s, on the Strand. Sitting alone in a small, dark recess in the factory wall, he would spend 10 hours a day cutting and pasting labels on to jars of shoe polish:

“My work was to cover the pots of paste-blacking; first with a piece of oil-paper, and then with a piece of blue paper; to tie them round with a string; and then to clip the paper close and neat, all round, until it looked as smart as a pot of ointment from an apothecary’s shop.”

For this, he was paid six shillings a week — around £18, or £3 a day, in today’s money.

The work was tiresome and tedious. The factory was filthy, freezing, and overrun with rats. Mistakes would be punished by beatings. For a sensitive, bookish boy — who only weeks before had been dreaming of fame and fortune — it was nothing less than hell on earth:

“No words can express the secret agony of my soul as I felt my early hopes of growing up to be a learned and distinguished man, crushed in my breast. The sense I had of being utterly neglected and hopeless; the shame I felt in my position; the misery it was to my young heart to believe that, day by day, what I had learned, and thought, and delighted in, was passing away from me, never to be brought back any more; cannot be written.”

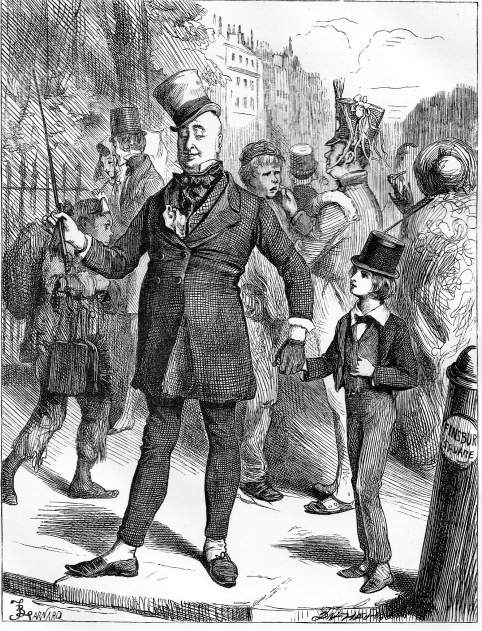

He had no friends, no prospects, and no hope of escape. A vague promise to provide him with a rudimentary education in his lunch hour was quietly forgotten. When the factory moved premises to the more upmarket neighbourhood of Covent Garden, wealthy passers-by would stop to gawp through the window at him as he worked — sharpening his awareness of the gulf between rich and poor. On those rare occasions when someone would slip him a few coins out of pity, he would go into a fancy restaurant and order the cheapest item on the menu — just to remember what it felt like to live a ‘respectable’ life.

His only amusement came from observing the colourful characters who worked alongside him at the factory — like Bob Fagin, a kindly elder colleague who taught him how to tie the string on jars of blacking — and who lived in the Marshalsea. On Sundays, when he would visit his family in the prison, they would furnish Charles with tales of the other inmates: the vivid details of which he would carefully store for future use…

John Dickens had been in prison for three months when a miracle occurred. His mother-in-law died suddenly, bequeathing the family a modest inheritance. It was enough to pay off John’s creditors — and buy his freedom.

But having grown dependent on the money Charles was bringing in, his parents insisted he remain working at the factory. A whole year would pass before he was finally permitted to return to school. Even then, his mother tried to persuade him to stay — a betrayal for which Charles never forgave her: “I never shall forget — I never can forget — that my mother was warm for my being sent back.”

Like so many family traumas, the whole episode was drawn beneath a veil of silence. No one in the family — Charles included — ever mentioned their misfortune again. “From that hour until this my father and my mother have been stricken dumb upon it. I have never heard the least allusion to it, however far off and remote, from either of them.” It was as though it had never happened…

When he finished school, Charles would find work as a clerk in a law firm. Having learnt shorthand, he became a parliamentary reporter, writing amusing summaries of debates in the chamber. To supplement his income, he began writing stories and sketches for magazines on the side: lively, comic slices of London life. In 1836, when he was still only 24 years old, he published the first instalments of what would become his first novel: The Pickwick Papers. After initially poor sales, the book would become a runaway bestseller, beginning his literary career.

Over the next 34 years, Dickens would publish more than 20 novels and novellas. They found him fame not only in the UK, but also in Europe and America, where crowds of eager fans would gather on the docks to await the arrival of the latest Dickens ‘number’. He met — and befriended — Queen Victoria, who received advanced copies of each new novel. Perhaps most gratifyingly of all, in 1856, he fulfilled his father’s prophecy — purchasing the very country house (Gads Hill Place, in Kent) he had once admired as a boy.

But throughout his life, virtually no one — not his readers, not his friends, not even his family — knew what had happened to Dickens as a boy. Mindful of how the stigma of crime and poverty would affect his reputation, he maintained his secret for the rest of his days. “From that hour until this, no word of that part of my childhood has passed my lips to any human being.”

He told his tale to just one person: his close friend — and first biographer — John Forster. After Forster pressured him for details about his past, he wrote a secret account of his family’s misfortunes and the year he spent at the boot-blacking factory, on the condition that Forster would publish it only after Dickens was dead. Forster was true to his word: when his biography appeared in 1872, two years after Dickens’s death, his own children were shocked to discover the truth about their father.

Yet — consummate writer of mysteries as he was — Dickens left clues everywhere. His experiences crop up, in disguised form, in his novels. There, we can find naive, spendthrift fathers, like Mr Micawber in David Copperfield (1850)…

Cold, heartless mothers, like Miss Havisham in Great Expectations (1861)…

Whole families locked up in the Marshalsea prison, like the Dorrits in Little Dorrit (1857)…

And child labourers, like Pip, Oliver Twist and David Copperfield, who are forever marked by the poverty and misery of their youth.

Now that Dickens’s secret is out, we can see how it shaped him in two key ways. Firstly and most obviously, it gave him first-hand experience of the systematic cruelties visited upon England’s poor. He became a lifelong social critic: using his novels as a vehicle to expose the worst excesses of Victorian society (its child labour and debtor’s laws being two prime examples) and advocate for reform. In this, he was often successful: a succession of Factory Acts aimed at improving working conditions for children were passed within his lifetime (though child labour would not be fully outlawed in the UK until the early 20th century), while the infamous Debtor’s Law was abolished in 1869.

Secondly — and perhaps more profoundly — it shaped his understanding of human psychology. Dickens’s conception of child psychology in particular is one of the most radical innovations of his fiction. The Victorian age sentimentalised childhood as a time of blissful innocence, free from worldly cares and concerns. But in Dickens’s novels, children bear full witness to the horrors of the adult world. They are all too conscious of the cruelties they suffer — and the injustice of a society which permits their infliction.

As Dickens’s own childhood taught him, our psyches are formed — and deformed — by our earliest experiences. All the fame, money and adoration he found in his later years could never fully heal the scars from his past.

“Even now, famous and caressed and happy, I often forget in my dreams that I have a dear wife and children; even that I am a man; and wander desolately back to that time of my life.”

He was thus one of the first authors to describe the phenomenon we now call ‘childhood trauma’. It is perhaps no coincidence that one of his closest readers was Sigmund Freud, whose interest in child development would become one of the founding pillars of psychotherapy.

For readers in the modern West, it is this aspect of his writing that merits closer attention. Though we may not have undergone the same level of privation as Dickens, our own childhood will have contained its share of misery and shame. Thankfully, we are no longer obliged to keep our experiences secret (or disguise them through fiction)…

As Dickens came to recognise, we must find a way to process and give voice to our childhood trauma — whether through writing or therapy — if we wish to recover from its effects.