Sociability • Communication

Communication

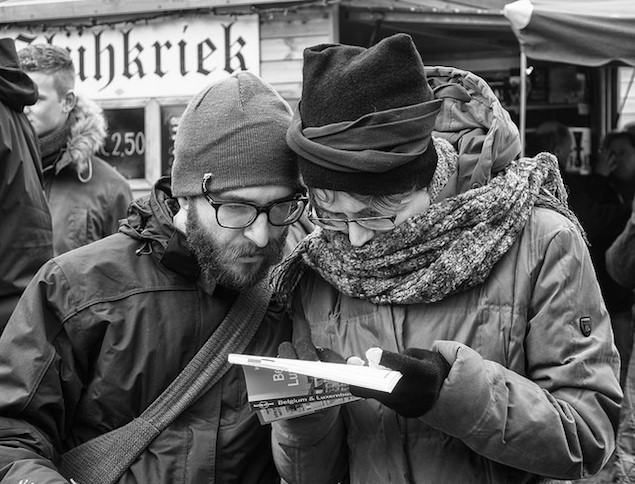

I: Sulking & the Fantasy of Wordless Communication

One of the most gratifying aspects of the early days of a relationship is the sense that our lover has been equipped with an extraordinary capacity to understand us intuitively – without us needing to explain ourselves in detail.

With other people, we are frequently mired in a requirement to construct pedantic tortuous explanations to convey our intentions – but a true lover seems to get us almost immediately, even in the finer-grained aspects of our personalities. No sooner have we tried to explain, for example, our feelings towards autumn evenings or a passage in a song we are especially touched by (when the violins start to rise against a deepening bass) that they generously step in to say, ‘I know, I know…’, seemingly ready to confirm our every sensation and idea.

This is a profoundly beautiful and exciting discovery. However, it is also one which gives rise to an impression with hugely dangerous consequences for the long-term success of our relationships: the belief that a true lover should and could invariably understand everything about us without us having to speak.

The belief is, over time, responsible for a catalogue of ills, most prominent of which is a catastrophic tendency to lapse into sulking.

Sulking is a highly distinctive phenomenon within the psychology of love. Crucially, we don’t just sulk with anyone. We reserve our sulks for people we believe should understand us but happen on a given occasion not to. We could explain what is wrong to them of course, but if we did so, it would mean that they had failed to understand us intuitively and therefore, that they were not worthy of love. People who may have been uncomplainingly articulate all day with colleagues at the office, with small children or relatives will, over an apparently minor misunderstanding with a partner, suddenly become obstinate and furiously uncommunicative, because these characters, of all people, should just know. A sulk is a sign of deep hope. One would never bother to storm out of a room, bang the door and refuse to say what was wrong for a few hours unless one held out very high hopes of a person. We don’t fall into sulks with most people because we have so little hope that they could ever understand. A sulk is one of the odder gifts of love.

The fateful hope reveals a debt to earliest childhood. In the womb, we never had to explain what we needed. Food and comfort simply came. If we had the privilege of being well parented, some of that idyll may have continued in our first years. We didn’t have to make our every need known: someone guessed for us. They saw through our tears, our inarticulacy, our confusions: they found the explanations when we didn’t have the ability to verbalise. That was the greatest kindness. It was an effort of love. Then came the struggle to learn to speak, driven in part by the failure of others to understand us well enough. Language is born from a degree of disappointment. Eloquence is a sign of how misunderstood we have felt in danger of being, of how badly we needed to be persuasive. But it is also why eloquence is an asset we may be highly unwilling to call upon in love. The most articulate among us may simply not want to explain ourselves within what should be the protective realm of a relationship.

In a more helpful culture than our own, we would be reminded that our partners may be very nice and at the same time very likely to misunderstand, without evil intent, a good number of our moods. Even at their best, they will be mistaken in their interpretations of a raft of our central needs. To calm us down in the midst of a sulk, we should be reminded that it is not really a sign of love for every aspect of our souls to be grasped wordlessly. It is no insult to us to be called upon to develop our eloquence. When our lovers fail to understand, it isn’t an immediate sign that they are heartless. It may merely be that, out of a Romantic prejudice, we have grown a little too committed to not teaching them about who we are.

In an ideal world, we would also more readily recognise (when we can manage a compassionate mood) the comic aspect of sulking – even when we are the special target of the sulker’s fury and rage. We would see the touching paradox. The sulker may be six foot one and employed by a major law firm, but they are in fact saying: “Deep inside, I remain an infant and right now, I need you to be my parent. I need you to guess what is truly ailing me, as people did when I was a baby, when my ideas of love were formed.”

The sulk can be overcome when this insane, touching ambition reveals its comedic dimension. We are then in a position to laugh, not because we don’t care, but because we understand how touching our fantasies of one another are. We are so alive to the notion of being patronised when considered as younger than we are; we forget that this is also, at times, the greatest privilege. We look beyond the sulker’s callous words and the slammed door. We grasp the real suffering beneath the horrible exterior, we see that our adversary is hurt not mean, and are struck – once more – by how oddly human nature is arranged. But because we understand, we are no longer frightened or angry in turn. The furious, hopeful, deluded absurdity of our partner’s trouble makes us gently smile. We get ready to knock at the door and gently ask if they might let us in for a word.

Part of becoming mature must be to believe that we cannot fairly continue to expect others to read our minds if we have not previously deigned to lay out their contents through the admittedly very cumbersome medium of words. Even the most intelligent, sensitive lover cannot be expected to continue to navigate around us without a lot of patiently articulated verbal indications of our desires and intentions. Those charming early lucky guesses about what our lovers feel should not fool us too long. Even in a very successful relationship, there is only a tiny amount that a lover should ever be expected to know of their beloved without it having been explained in language. We shouldn’t get furious when our lovers don’t guess right. Rather than bolting our mouths and retreating into the comforting silence of a sulk, we should have the courage – always – to try to explain.

1. Teaching & Learning

In theory, we respect teachers. But being a teacher isn’t glamorous. It’s a worthy – but slightly dull – profession. Because we associate teachers so strongly with schools, it’s natural to assume somewhere in our minds that ‘teaching’ is something most people leave behind as they grow up. We tell ourselves that it takes a very special type of person to be a teacher – and assume that we’re just not cut out for that kind of role.

But in truth, being a teacher is one of the most central aspects of human life. Even if we don’t sign up to instruct adolescents in chemistry or history in a school, we will have to become teachers. There is no alternative but to master the art of teaching. Teaching just means getting an insight, emotion, state of mind or a skill from your head into the head of someone else. Teaching happens every hour of every waking day. But we’ve fatally misconstrued teaching as a specific professional job, when it’s in actuality a role that everyone has to dip into continually.

There is so much to teach in love. Troubles in relationships are almost always, at heart, related to poor teaching. There are things in our heads we can’t get across and things in theirs we can’t grasp. Misunderstandings abound and fury and resentment rises. The flashpoints might come around sex. There’s something you’d really like to do in bed with your partner; but you’re very nervous about how they might respond. The tendency is to feel it’s hopeless – and therefore not to teach at all. Or to get insistent and panicked – which turns your partner off.

Perhaps the problem comes around work: you’d love to have your partner’s sympathy; but they’d need to understand quite a bit about the situation you’re struggling with at the office: why the strategy you’ve been pursuing doesn’t seem to be working, but is actually a good idea; why a certain colleague’s support turns out to be worse than their hostility; why the situation in Mexico matters so much. But getting them up to speed on all this is so hard, you want them just to understand already.

There are failures of teaching around domestic issues too. You get enraged by things like the way your partner stacks the dishwasher; by how they close the cupboard door in the bathroom; by their over-confidence about getting to the airport on time. You would like the partner to know, but it seems beneath both of you to have to go into ‘small things’ in laborious detail. You both feel that some things are too petty to need to be discussed carefully.

Another huge underlying educational theme of relationships is teaching your partner about yourself. It’s a matter of trying to get them to understand the nature of the person they’ve got together with. The fact that – for you – certain things are extremely difficult which others take in their stride. Maybe you find filling in forms unbelievably challenging – not because you are lazy or irresponsible. But because form-filling was always your father’s thing and he made it seem terrifying and dangerous, it was something only he could do. In love, we might – for example – find it very hard to teach each other the difference between rejection and the need for solitude. Perhaps you really need to spend quite a lot of time alone not because you want to reject your partner, though that’s how they see it, if they don’t understand you properly; in fact it’s because there’s such a lot of things going on in your head that you need time with very low input to try to calm down. Ultimately, it can seem a mystery why you are the way you are. But the more careful explanation is often much less alarming that the worried.

There are a number of qualities that we need to learn to become better teachers. For a start, we need a confidence that teaching is a legitimate activity to pour our energies into; that we have the right to instruct others. We are the unfortunate inheritors of a Romantic tradition that constantly militates against the ambition to teach, recommending instead that we be enthusiastic about spontaneous, intuitive communication. Outside of obviously technical fields, we get impatient with teaching. We understand there needs to be teaching when it comes to learning to ski or work out the area of an isosceles triangle. But we’re often quite resistant to the idea of ‘teaching’ around the core issues of human existence – who should one marry, what is beautiful or ugly, what the media is for, what cities should look like – we turn against the idea that there can be teachers, because we’re collectively inclined to the Romantic notion that these topics are purely personal and that wisdom can’t be transmitted. So no one has any right to teach.

In turn, we are bad students. We feel that no one should be in a position of authority, especially within a relationship. We often bristle if someone tries to tell us what to do or how to think. It is a kind of healthy democratic headwind against which any desire to teach (to get others to learn from you) has to contend.

What we need to burn into our souls is the idea that – all the same – it is actually perfectly legitimate and reasonable to try to teach. Everyone has a lot to learn and everyone has something important to impart to others. We should also be deeply aligned with the approach of classical culture: seeing most human activities are areas where learning and teaching are possible and important.

Instinctively, we often suppose that what we say will be more authoritative and carry more weight if we can present ourselves as pretty much perfect. If you don’t make mistakes, you are going to seem right. Unfortunately, however, this attitude is very rarely shared by anyone who is on the learning side of the equation.

Yes, we want to be reassured that the person doing the teaching knows what they are talking about in this particular instance. But the potential for the humiliation of the one learning is never far from the surface. We easily resent being taught. We easily feel that the one doing the teaching is showing off. All this might be very untrue in fact. But it’s the fact that we feel it that creates the obstacle to learning. Being taught places the student in a position (however momentary) of inferiority. You have something, they don’t.

So if you’re teaching, it’s tremendously useful to surround any ‘lesson’ with active reassurance that you are on the same level basically – this lesson aside. Show that you too have faults, are often clumsy and goofy. Show that you too don’t know many things. You need to show areas of inferiority so that your own superiority in the teaching area won’t stick out and offend.

It seems paradoxical – once it is pointed out. But the fact is we often get very annoyed that someone doesn’t know something yet – and we assume they should, given who they are, at this point in their life, with their track-record… And so we go about the business of teaching them with a background grudge; we feel it’s their fault; they don’t know so they must be stupid, lazy or in some way inadequate. And this attitude makes it unlikely that what we have to teach will actually make its way successfully into this person’s head.

A lot of good teaching starts with the idea that ignorance is not a defect of the individual: it’s the consequence of never having been properly taught – however old one or ostensibly ‘educated’ one happens to be. So the fault, rightly, really belongs with other people who haven’t done enough to get the needed ideas into this individual’s head or simply with the brute fact of belonging to our deeply flawed species.

Being in the right mood is a huge factor in how well we learn. We instinctively recognise this about ourselves. We feel too tired, too bothered about other things, too excited to take in anything tricky or serious. But it’s much harder to acknowledge this fact when it comes to other people.

We tend automatically to try to teach the lesson at the moment the problem arises, rather than selecting the moment when it is most likely to be attended to properly.

Mood is also crucial to how well we can teach, the more desperate you feel inside, the less likely you are to get through effectively. Unfortunately, we typically end up addressing the most delicate and complex teaching tasks just when we feel most irritated and distressed.

There’s a panicked feeling that if I don’t jump on this right now it’s going to go on and on unchecked forever. Picking one’s moment means being very sure that you can avoid tackling something right now because you are determined to address it more effectively later on.

Being skilled at timing has often been recognised as a major virtue and accorded high prestige – in the history of warfare, for instance. In 9 AD Germanic tribes won a major victory over the Roman legions. The less well equipped German tribesmen won because they chose their moment well – when the legions were passing through a thickly-wooded region and couldn’t form up in their accustomed order. Up until then, the Roman generals had assumed that the Germanic tribes would be unable to pick their moments wisely, but would always get so enraged by the sight of the enemy that they would attack on impulse.

By picking their moment, the fortunes of the Germanic tribes were transformed. Given how central teaching really is to our lives, and how much opportunity is squandered by poor timing, it’s strangely sad that we haven’t as yet developed a cult of great timing in addressing tricky matters in relationships or at work, passing down the stories from generation to generation of how, after years of getting nowhere with impulse-driven frontal assaults, she stood patiently by the dishwasher, waiting until she had put down the newspaper, and then carefully advanced her long prepared point, and eventually won a decisive teaching victory.

We have to teach all the time; but teaching is hard. Every day you’re called upon to perform these educational moves – at work, at home, with friends – without ever having signed up to the task. You didn’t ask to be a teacher.

The topics might be quite dissimilar – a lesson on how to put the butter back, how to code a piece of the website, how to cope with rejection – but they share many similar features. And they all boil down to the same core: how do you overcome the obstacles to getting what you understand into someone else’s head?

Our society hasn’t as yet fully taken on board the scale of the challenge. So we don’t as yet have in place an educational system that assumes everyone is going to have to get good at teaching.

But it would be unfair to place the responsibility solely on the idea of teaching. There’s also the parallel, universal role of being the student. We all have to accept that other people have the right to try to teach us things (that we’re far from perfect) – and that they may be trying to teach us something very valuable, even if they’re making a complete mess of it. We must forgive the unskilled teacher, there may be a grain of truth beneath some blundering efforts.

When someone is doing the teaching process badly, it’s unfortunately natural to assume that they don’t have anything to teach. And that what they are trying to get across is wrong. If you’re being boringly nagged about not eating enough broccoli or about the importance of checking the window locks before going out, it’s deeply tempting to reject not just the annoying way you’re being told, but also the validity of what you are being nagged about. We don’t just feel like shooting the messenger. We also want to shoot the message.

The core point is taking seriously the idea that we’ve still got a lot to learn from other people and that being a student is a skill – even if the teacher isn’t up to scratch we can still extract a benefit from what they know that we don’t.

There’s a hopeful side to all this. We’re not as yet generally focused on learning how to teach; but it’s not a huge mystery. We already know collectively a lot about good teaching: we’re just not ambitious enough about deploying this knowledge very widely. We’ve seen teaching as a specialist professional skill that only a few people need to master. In fact, we’ve all got to get better at it in order to have somewhat less fractious lives.

III. Love & Criticism

One of the most delightful and thrilling aspects of the early days of a love affair is the sense that our lover likes us not only for our obvious qualities – perhaps our looks, or our professional accomplishments – but also, and far more touchingly, for our less impressive sides: our vulnerabilities, our hesitations, our flaws. Perhaps they are particularly taken by the gap between our two front teeth which, while it wouldn’t impress an orthodontist, charms them distinctly. Or perhaps they are taken by our shyness at busy parties or are powerfully drawn to that old pair of pyjamas with the bear prints which we put on on cold winter nights and which would win no fashion award.

This creates a beguiling prospect of what love might be – but one which also sets up a desperately unfair and unhelpful expectation: the belief that really being loved by someone must involve being endorsed for every aspect of us, our good sides, but also, more particularly, our weaknesses too.

This pleasant vision may last a few months into a relationship but eventually, something is likely to disturb it. We will notice something about the lover which is both a flaw and not especially charming. Perhaps it’s their rather bovine way of eating cereal, their habit of not hanging up towels or their maddening tendency to withhold crucial bits of bad news from us.

But because of the belief that love means complete endorsement, there is likely to be an incensed hurt response from a partner. What is feedback doing in the hallowed realm of love? ‘If you loved me, you wouldn’t criticise me’ can be love’s all too common wounded rallying cry.

This protest against teaching from a lover is so ubiquitous that we forget to notice its strangeness. It represents a very particular approach to love and not necessarily the wisest. For a more helpful take, we might look back to the Ancient Greeks, who had a strikingly different philosophy of feedback within love.

For the Greeks, love is not meant to be an emotion centred on just anything at all about the partner. Rightly understood, it is a very specific feeling that targets what happens to be accomplished, perfect, virtuous and intelligent. Around the other less impressive things, one must be tolerant and understanding of course – but one isn’t expected to love. The word love is restricted to a particular sort of admiration for perfection.

Connected to this, for the Greeks, is a sense that the point of a relationship is to be a forum in which two people can help each other to increase the number of admirable characteristics they each possess: it is to help them become the best version of themselves. The Greeks held to a fundamentally pedagogical view of love; they understood that a relationship gives us a ringside seat on one another’s flaws and potential – and therefore believed that both partners should take it in turns to act in the role of teacher and student – attempting to educate the other to become a finer person within the safe and encouraging confines of love’s classroom.

All this is likely to sound incredibly strange to modern ears. The notion that the point of love is to help to teach the lover to become a better version of themselves, and therefore that one might legitimately deliver lengthy lectures to one’s partner on how their character might be improved sounds like a freakish, dictatorial betrayal of the true nature of love.

Yet, in truth, there is a lot of wisdom in the Greek position – for we can interpret many of the struggles people have in relationships as being, in essence, failed teaching moments; moments when one or the other party attempt to get something across, possibly a very well-founded point, but see their lessons rejected in bitter and hurt tones.

The reason why the lessons we try to impart in love’s classroom tend to go so wrong is that we are respectively very bad teachers and very bad pupils. And part of the reason is that we don’t – in the role of teachers – have any real sense that we are even allowed to teach, which makes us panicky and defensive. Furthermore, what helps someone to be a good teacher is a relaxed sense that it doesn’t in the end matter so much if the lesson is learnt or not. A good maths teacher wants to get the basics of trigonometry across to the class, but if they are being obtuse, they can be calm; there’ll be another student cohort along next year.

But love’s classroom finds us in a far more agitated state – because at the back of our minds as we try to teach a point is an utterly panic-inducing thought: that we may have committed ourselves to an idiot who will continue in a range of erroneous ways for the rest of our days.

It’s on this basis that we start to swear, belittle and insult our lover. Which is understandable but very unfortunate, for it seems that sadly no one has ever learnt anything under conditions of humiliation. By the time one has made the partner feel like a fool, the lesson is over.

It seems that a good relationship should be a forum in which we teach each other many things and gracefully learn in turn. If we understand ourselves properly, we will know that there are so many sides of us that need improvement. For that reason, we should learn to see love a little as the Ancient Greeks did: as a safe arena in which two people can gently teach and learn how to grow into better versions of themselves. Teaching and learning doesn’t symbolise an abandonment of love; it’s the very basis upon which we can develop into better lovers and, more broadly, better people.

IV. No such thing as a small issue: The Dignity of Ironing

When intelligent and sensitive people – guided by Romanticism – come together in relationships, they tend to be agreed on an implicit hierarchy of what is and isn’t important for the success and endurance of their love. They tend to be highly aware of the importance of spending time together (perhaps in museums or by the sea), of having fulfilling sex, of assembling a circle of interesting friends and of reading stimulating books. They are unlikely to give much thought, however, to the question of who will do the ironing.

Part of the reason is that when Romantic writers explored the troubles of relationships in their works, they never talked about laundry. They tended to draw attention to an important, but notably limited, range of issues. The great Russian poet, Alexander Pushkin, depicted unrequited love in Eugene Onegin. Gustave Flaubert examined boredom and infidelity in Madame Bovary. Jane Austen was acutely attentive to how differences in social status could pose obstacles to a couple’s chances of contentment. In Italy, the most widely read novel of the 19th Century – the Betrothed by Alessandro Manzoni – discussed how political corruption and large historical events could overwhelm a relationship. All the great Romantic writers were – in their different ways – deeply interested in what might make it hard for a relationship to go well.

Yet there has always been something major missing from their list. There has never been much interest in any of the challenges that fall within the realm of what we can call the ‘domestic’, a term that captures all the practicalities of living together, and extends across a range of small but crucial issues, including who one should visit on the weekend, what time to go to bed, how often one should have friends over for dinner and who should buy detergent.

From the Romantic point of view, these things cannot be serious or important. Relationships are made or broken over grand, dramatic matters: fidelity and betrayal, the courage to face society on one’s own terms or the tragedy of being ground down by the demands of convention. The day to day minutiae of the domestic sphere seem entirely unimpressive and humiliatingly insignificant by comparison.

Partly as a result of this neglect, we don’t go into relationships ready to perceive domestic issues as important potential flashpoints to look out for and pay attention to. We don’t acknowledge how much it may end up mattering whether we can maturely resolve issues around the eating of toast in the bed or the conundrum of whether it is stylish, or a touch pretentious, to give a cocktail party.

When a problem has high prestige, we are ready to expend energy and time trying to resolve it. This respect leads to an unexpected but crucial consequence. We don’t panic around the challenges, because we understand the difficulty of what we are attempting to do. We are a lot calmer around prestigious problems. It’s problems that feel trivial or silly and yet that nevertheless take up sections of our lives that drive us to heightened states of agitation. Such agitation is precisely what the Romantic neglect of domestic life has unwittingly encouraged: its legacy is over-hasty conversations about the temperature of the bedroom and curt remarks about the right channel to watch, matters which can – over years – spell an end to love.

Long running, highly stressful domestic anxiety often circles around what look like pedantic details. What is the right way to cook a chicken? Should newspapers be kept the bathroom? If you say you are going to do something ‘in one minute’ is it OK to actually do it eight minutes later? Is it extravagant to drink carbonated bottled water everyday at home? They naturally provoke the thought that it is somewhat idiotic to get bothered about them. And so a path often recommended for a calmer relationship is that we should simply stop caring about such matters: that we should stop obsessing over ‘details’.

In the arts, we acknowledge that small things – details – are densely packed with significance. Domestic details, too, look small but carry big important ideas. It might sound very odd at first to make the comparison, but the objects of domestic agitation are very like works of art: they condense complex meaning into tightly packed symbolic details.

We might typically associate panic with the presence of a difficult task or an urgent demand. But that’s not quite right. What actually causes panic is a difficulty that hasn’t been budgeted for or a demand that one has not trained or prepared to meet. The road to calmer relationships therefore isn’t necessarily about removing points of contention. It’s rather about assuming that they are going to happen and that they will inevitably require quite a lot of time and thought to address.

If we admit that sharing a space and a life is very difficult – and yet very important and worthwhile – we come to conflicts with a very different attitude. We will argue about who puts out the bins, who gets more duvet and what we watch on TV… but the nature of the struggle will change. We won’t necessarily immediately get so impatient and so rude. We’ll have the courage of our dissatisfaction – and patiently sit with a partner for a good-natured two-hour discussion (perhaps with a Powerpoint presentation) about the sink and the crumbs and the shirts – and thereby help to shore up our love.

V. Artificial Conversations

Good communication means the capacity to give another person an accurate picture of what is happening in our emotional and psychological lives – and in particular, the capacity to describe their very darkest, trickiest and most awkward sides in such a way that others can understand, and even sympathise with them. The good communicator has the skill to take their beloved in a timely, reassuring and gentle way, without melodrama or fury, into some of the trickiest areas of their personality and warn them of what is there (like a tour guide to a disaster zone), explaining what is problematic in such a way that the beloved will not be terrified, can come to understand, can be prepared and may perhaps forgive and accept.

We’re not naturally skilled at these kinds of conversations because there is so much inside of us that we can’t face up to, feel ashamed of or can’t quite understand – and we are therefore in no position to present our depths sanely to an observer, whose affections we want to maintain. Perhaps you have completely wasted the day on the internet. Or you are feeling sexually restless and drawn to someone else. Or you are in a vortex of envy for a colleague who seems to be getting everything right at work. Or you’re feeling overwhelmed by regret and self-hatred for some silly decisions you made last year (because you crave applause). Or maybe it’s a terror of the future that has rendered you mute: everything is going to go wrong. It’s over. You had one life – and you blew it. There are things inside of us that are simply so awful, and therefore so undigested, that we cannot – day-to-day – lay them out before our partners in a way that they can grasp them calmly and generously.

It is no insult to a relationship to realise there’s a shortfall of mutual eloquence and that this will probably require some level of artificiality. Our need for assistance is often especially acute around anger, desires that seem strange and the need for reassurance (which tends to arise when one feels one doesn’t especially deserve it). We should not feel that we are failures, dull-witted, unimaginative or unsophisticated if we recognise a theoretical need to learn how to talk to our partners with premeditation and conscious purpose. We are simply emerging from a Romantic prejudice.

An artificial conversation can sound like quite a strange idea. But what it involves is just deliberately setting an agenda and putting a few useful moves and rules into practice.

Over dinner with a partner, we might for example work our way gradually yet systematically through a list of difficult but important questions that otherwise we’d likely shelve:

What would you most like to be complimented on in the relationship?

Where do you think you’re especially good as a person?

Which of your flaws do you want to be treated more generously?

What would you tell your younger self about love?

What do I suspect I might get wrong about you?

What is one incident I would like to apologise to you for?

What is one incident I feel you should apologise to me for?

How have I let you down?

What would you want to change about me?

If I was magically offered a chance to change something about you, what do you guess it would be?

If you could write an instruction manual for yourself in bed, what would you put in it? (Both take a piece of paper and write down three new things you would like to try around sex. Then exchange drafts).

Another thing we can do with a partner is to finish these sentence stems about our feelings towards one another – the idea is to finish them very fast without thinking too hard. What emerges isn’t of course a final statement. But it helps to get awkward material into the light of day, so that it can be examined properly.

I resent…

I am puzzled by…

I am hurt by…

I regret…

I am afraid that…

I am frustrated by…

I am happier when…

I want…

I appreciate…

I hope…

I would so like you to understand…

Part of the artifice here to agree in advance is not to be offended by what each other says, though some of what comes up is bound to be at the very least disconcerting. Instead of saying ‘how dare you say that, or I always suspected you were horrible, now you’re admitting it’, one should steel oneself in advance (for the sake of the relationship) to say instead something like: ‘I’m listening carefully, can you go into more detail?’ The idea is to set up an occasion on which for once it is possible to look carefully at genuinely awkward aspects or what’s going on between you. The helpful background assumption is: of course there will be many difficulties, because you can’t have a close relationship without there being a lot of sore spots on both sides. We’re not (for a bit) going to be angry with one another. We’re going to get to know what’s happening.

One might also try an exercise of fleshing out the following sequences:

When I am anxious in our relationship, I tend to…. You tend to respond by…. which makes me…

When we argue, on the surface I show ……, but inside I feel….

The more I ….. the more you….. and then the more I….

The aim here is to discover patterns of interaction, and how they look when seen from both sides. We’re trying to identify repeated sequences of emotions. Not to validate or condemn them but to understand them. The premise of this artificial conversation is that we’ll both be unaware of some of the things that go on between us. And that (for the duration of the conversation) no one is held to blame. We’re just learning to notice some problems with how we interact.

Relationships founder on our inability to make ourselves known, forgiven and accepted for who we are. We shouldn’t work with the assumption that if we have a row over these questions, the opportunity has been wasted. We need to be able to say certain painful things in order to recover an ability to be affectionate and trusting. That is all part of the particular wisdom and task of a more artificial, structured and emotionally-conscious conversation.