Work • Consumption & Need

“Giving Customers What They Want”

Many new and potentially very worthwhile ideas for products and services are routinely cast aside by companies with the objection: we must give customers what they want. Which really means: what we have sold them (and prospered from selling them) until now.

Beneath this response lies a widespread view that consumers must already have a clear and settled idea of what they are looking for in any particular area – and that this cannot change any more than the cycle of the planets or the laws of motion. Reference to customer taste is therefore a reason to close down any suggestion that deviates from present patterns of demand.

At its worst, an idea of the unbudgeable nature of customer desire becomes a justification for a businesses to serve up fairly dispiriting things. It explains the dogged adherence to mediocre food:

Underwhelming architecture:

Unambitious TV:

And standardised holiday offerings.

The idea of giving customers what they want feels powerful for several reasons. It’s always tempting to stick with a currently successful model that paid for your office, pension scheme and (perhaps) jet. It can also seem arrogant or plain snobbish to hint that there might be a way in which customers don’t quite know what they want – and that you might be the person to understand tastes they’ve as yet given no evidence of having. Finally, insisting you have the answer to the unexplored wishes of consumers can put you in a recklessly vulnerable position in the politics of the office.

The consequence is that avenues of pleasure and satisfaction go unexplored and opportunities for growth are set aside – and move elsewhere (normally to start-ups). Many people in a given corporation may well feel unexcited by the current focus. They might be working fairly hard to meet their sales targets but they are running only for the money rather than tapping into the great resources we find in ourselves when we truly believe in what we are doing. Yet, when someone says that perhaps the business could offer something more impressive, the same answer tends to come back: we have to give people what they want. It’s a way of thinking that lends confidence to the most conservative impulses in our nature.

But the core notion of ‘giving the customer what they want’ is profoundly under-examined and worthy of critical assessment. Of course, the idea of pleasing customers is not in dispute. What needs to be targeted, however, is the mistaken assumption – working away in the background – that what people want is a fixed factor – when in truth, what people want is dramatically malleable, contingent and divergent.

The idea that what people want is already well established is invariably based on a very small time frame and geographically-bounded sample-size. All we need to do is widen the angle of observation, and a remarkably different picture always emerges. For anyone seeking the confidence to make changes, there’s one unexpected place for immediate inspiration: the history of Culture.

When we look back in time, we see an extraordinary range of foreign concerns that seem to violate what we currently understand as consumer taste. For example, in 18th century Britain, members of the same species as we belong to today, the species reputed only to have an appetite for talent shows and celebrity quizzes on TV, got interested on a big scale in poetry. Alexander Pope, the leading poet of the day introduced the twelve syllable hexameter (against the advice of many) and was convinced that consumers would be highly sensitive to its rhythms. He was right. People loved the slightly slower pace and the neater rhymes it made possible – and he was able to buy himself a magnificent villa, just outside London, on the proceeds.

How did a poet earn enough to have this house?

In an age when we tell ourselves that the only way to be erotic is to reveal more of our bodies, we can take inspiration from a look back to 18th century English fashion, when covering everything except your angle was all the rage.

A tiny lift in the hemline gave ankles a new meaning

The raking of gravel is not something that, at present, seems like a major human concern. But in Japan, over many centuries, people became interested in the patterns into which gravel could be arranged in even very small gardens. Getting it right was hugely important to them. They also became very sensitive to the different characteristics of moss and the best ways of grouping rocks together. It’s evidence of how – under the right encouragement – large groups of people can become highly sensitive to features which, in other societies, go entirely unnoticed.

There have been so many moments in cultural history where huge leaps occurred in the kind of things people realised they could like.

There were plenty of people at first who were convinced the public would never go for works like this

In 1874, the First Impressionist Exhibition met with immense abuse. There was a widespread feeling amongst art dealers that the public would never warm to things which were so different from what they were currently buying, with brushworth that was choppy, deliberately disjointed and imprecise. However, within a few years, the art market was transformed.

Until 1915 most sculpture looked rather like this:

Then people quickly started getting more excited by this:

These cultural instances reveal a fundamental fact about how the whole basis of our excitement can shift in dramatic ways. Taste is a variable factor. We’re very good at appreciating moves of taste in retrospect – but in advance we are so much less alive to the inevitable repetition of the phenomenon. Therefore, businesses routinely end up assuming that their customers don’t care about anything they are not currently getting; and get bogged down in the worry that if they introduced something they feel is better – but rather different from current offerings – they will be punished. Such timidity tends to doom them.

Many businesses could be expanded, redefined or started on more competitive lines by taking consumer demand to new and very good places. There are three guiding principles for changing consumer taste:

1. Doing it with Confidence

If you have a good idea which is at the moment out of kilter with the norm, it’s important to be entirely unapologetic. Friedrich Nietzsche is arguably the most admired philosopher of all time; thousands of graduate students are currently writing theses using his ideas. But for much of his career he was an isolated individual living in cheap hotel rooms. But you can’t tell this from his books, which are miracles of confidence. He continually announces himself as the voice of a new era and insists that all philosophy hitherto has been awaiting for his insights to be properly useful. You don’t get the impression that he’s living with almost no friends or that he can’t afford a new pair of shoes.

Nietzsche is demonstrating that confidence is a powerful psychological tool: the well-expressed sureness of one person is infectious. Confidence relies on a crucial insight: people looking on are less securely wedded to their current beliefs than we usually suppose. The confident person remembers that most people want to fit in. So if you carry it off, they will fit in with you.

2. Connecting yourself to the Past

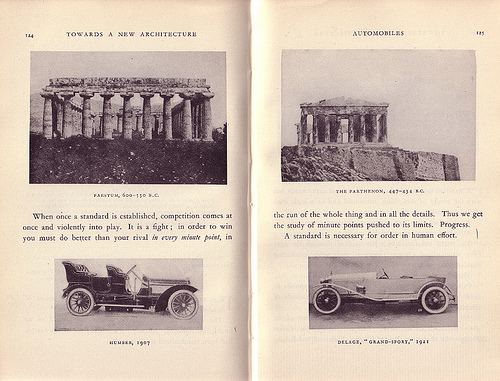

When the Swiss architect Le Corbusier wanted to enthuse the world about modern design, he made a move all innovators can learn from. Rather than saying that modernist architecture was new, he went far out of his way to show that it was in fact a direct continuation of the most revered traditions of the architecture of the past. It was more loyal to the past than more recent work. His polemical text, Towards a New Architecture, repeatedly drew analogies between the modern things he liked, cars and planes especially, and the most prestigious objects of Ancient Western culture. He was placing what he – and people like him – approved of in a bigger narrative, laying claim to a sense of natural progression. He wasn’t just making this up as a convenient cover story. He was helping his audience to trust that what was new was in fact, all along, faithful to what they already loved.

Picasso made a similar move when in 1957 he painted his own version of one of the central masterpieces of European art: Las Meninas by Velázquez (painted in 1656). Picasso’s style was radically different from that of his predecessor. But Picasso was situating his work within the grandest tradition of artistic ambition, teaching his viewers that respect for tradition was entirely consistent with enthusiasm for his own work.

3 . Refusing all market research

A standard idea of companies seeking to innovate but at the same time cover their backs is to commission market research – hoping thereby to discover the latent but till now unexplored needs of their customers.

But asking people about their preferences can never give us valuable clues as to what they could, perhaps quite soon, come to want – given the right prompting – because most of us are simply not self-aware enough to know what is missing from our lives. We know what we like when, but not a minute before, we are given it. We cannot know the shape of our future needs, no more than bookshop browsers in 1910 could have given a pollster an accurate description of their appetite for In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust, a novel that these customers would nevertheless be enjoying in large numbers only a few years later.

The only way to produce the products of the future is to interrogate one’s own soul with sufficient tenacity and insight. In other words, to be creative. An over-reliance on market research is a fateful obstacle to innovation (and therefore growth and profit), for it can never show us how things that do not yet exist will answer to an audience’s tastes.

Conclusion

The idea that companies should simply give people what they want isn’t as powerful a route to safety as it can sound. It is indeed at odds with the bigger facts of culture which show just how flexible, surprising and fast-moving change often is.

We are still at the dawn of the history of commercial opportunity. At the moment we have firmly in our sights certain needs which have produced reliable returns – the need for petrol cars that are individually owned, for large handbags with golden clasps, for TV shows with large laughing audiences… But, comparatively speaking, we’ve barely scratched the surface of human needs. There might be so many new and different things we could come to care about. To close, we’d like to sketch very briefly how four large commercial areas could evolve.

The News

The news industry is going through tough times. Suggesting that this has anything to do with the quality of the product is likely to receive a sharp rebuff from those in the business. The diet of murders, celebrity stories and sarcastic interviews with politicians is apparently exactly what the public wants. But is it really? Might there be room for innovations that appeal to different sides of our natures, sides of us that love sex but not sexual titillation, that want things to be entertaining but meaningful, that want to know bad news but also remain purposeful and resilient?

The houses we build

Property developers tell us that taste in housing has all been settled long ago. Customers want either glass towers filled with apartments or else neo-Georgian villas in the suburbs. At the moment some of the biggest architectural developments around the world are assessed only with respect to a couple of areas of interest: are they the tallest in the world and is their shape similar to some small item like a piece of fruit or a phone? But in principle we, the audience, could be sensitised to other, possibly more important, characteristics: do our homes enhance the skyline, do they sit nicely amongst their neighbours at street level or how will they look in 50 years time?

How we go on holiday

At present holidays are categorised by destination: beach, city, mountains and so on. Very little attention has been paid to one’s more emotional desires: to repair a relationship, to bond with the family, to make new friends, to spend time alone. We’re not collectively sensitised to new and potentially very helpful ambitions about what a holiday could be for.

The fast-food we eat

Apparently it has to be burgers and fries, especially when we are in a drive-in. But we’re the same species that, in 16th century Japan, ate squid and fried eel on the go – and in Ancient Rome, snacked on marinated duck livers. A far wider road lies open before us than we have as yet dared to imagine.