Leisure • Small Pleasures

How Giraffes Can Teach Us to Wonder

We may be sad because we think we know it all, because everything has grown stale and familiar — because we have (for very understandable reasons) lost the ability to wonder.

Yet the world is always stranger and more unexpected than we can bring ourselves to believe in our dejected moods. Zhu Di, the third Emperor of the Ming dynasty (1402 to 1424) had by middle age grown weary of his role as royal intermediary between heaven and earth; he had a thousand mistresses, he’d conquered Vietnam and tamed the Mongols and he’d commissioned the largest book ever written, the Yongle Encyclopedia, that explained every element in the history of Chinese civilization. But, weary in his soul, the Emperor made a move that none of his predecessors had ever attempted. He sent some ships to explore the wider world. Chinese rulers knew their country to be the most interesting and blessed on the planet and therefore generally felt no need to go elsewhere — beyond at most subduing a near neighbour. But Zhu Di asked his explorer and mariner, the eunuch Admiral Zheng He to go out and make a thorough survey of all barbarian lands he could find. With a more or less unlimited budget, Zheng He had a vast fleet built in the Longjiang shipyard near Nanjing and after a banquet presided over by the Emperor at which sacrifices were made to Tianfei, the patron goddess of sailors, China’s largest ever expeditionary force set off. It dropped in on Brunei, Java, Thailand, Ceylon, India, and then went over to Arabia and Africa, stopping at Hormuz, Lasa, Aden, Mogadishu, Brava, Zhubu, and Malindi.

Along the way, the Admiral picked up a panoply of gifts and treasures that he hoped would amuse and delight the emperor: manuscripts, sculptures, clothes, gold, palm and date trees, figs, all manner of spices, a few slaves and many new concubines. But what the Emperor really loved were animals and the Admiral picked up a veritable-zoo full that had never been seen before in China: lions, leopards, dromedary camels, ostriches, zebras, a rhino and antelopes.

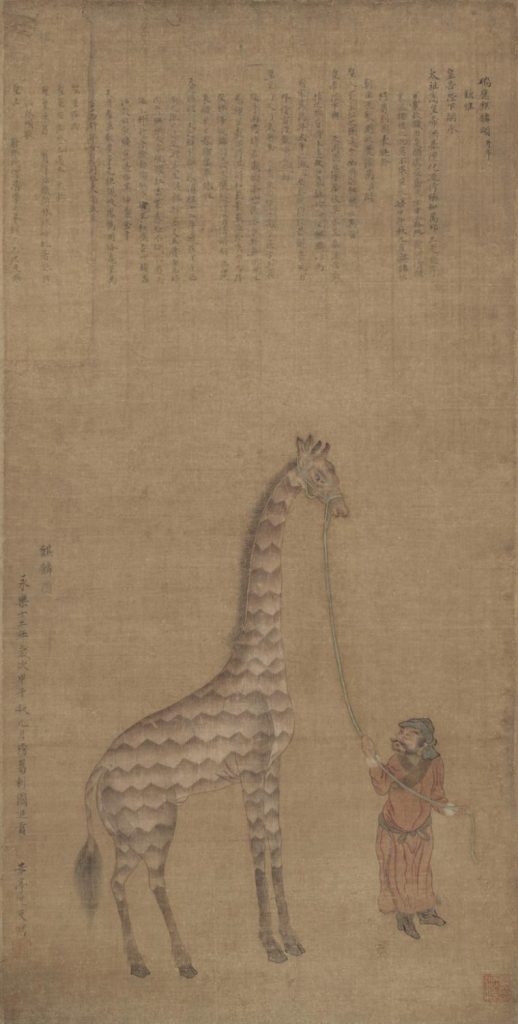

What the Emperor turned out to really love was one animal in particular: a giraffe that his Admiral had picked up from a couple of intrepid Kenyan traders in eastern India. Laying eyes on it for the first time, he stroked the animal’s hide, marvelled at its long neck and graceful but slightly awkward way of walking — and gave it his blessing. His spirits having lifted, the Emperor invited the entire court to take a look. He had an enclosure especially built for the giraffe in his palace and often took walks with it around the grounds. Unsurprisingly, he asked his artist, Shen Du, to capture his new friend, an honour he did not bestow on any other foreign animal.

We probably all had some of Emperor Zhu Di’s excitement when we first laid eyes on a giraffe, at the age of three. We too would have marvelled at that long neck and admired the bright patterning and strange gait. But somewhere along the line, we stopped wondering; about giraffes and pretty much everything else as well. The world became familiar and then stale.

We should not, perhaps, have given up so easily. Giraffes remain hugely odd and importantly wonderful. We do not live on a dull planet, we have allowed our sorrows to drain our capacities for joy. We should, when depression weighs us down, strive to remind ourselves that the world remains full of giraffes, and what they symbolise: renewed charm and creativity, new opportunities for interest and fresh reasons to keep going.