Work • Utopia

How Science Could – at Last – Properly Replace Religion

According to a standard heroic secular account, at the start of the modern age and in just a few short decades, science was able to defeat religion through rigour and brilliance – and thereby forever liberated humankind from ignorance and superstition. For centuries, this account explains, religion had essentially been doing some very bad science. It had purported to tell us how old the earth was (4,000 years old), how many suns there were in the universe (one), how evolution had begun (by divine decree) and why rainbows existed (to remind us of God’s promise to Noah). But these lamentable attempts were finally put to an end when science was able to investigate reality with reason, asserted itself against obscurantist priests – and drove religion into the cobwebbed attic it presently resides in. Science didn’t so much replace religion (there was no need) as expunge the scourge altogether from human consciousness. As a result, we can now dwell without fear or meekness and enjoy the fruits of science and its constant, ever more astonishing technological innovations.

The story is highly seductive in its robustness and has a pleasingly victorious feel to it as well. But it may not, for that matter, be entirely true. It willingly (and cleverly) misrepresents the purpose of religion, by positioning it as an entity whose overwhelming focus has been to do pretty much exactly what science does – and by then pointing out that it happened to do it very badly. Whereas science was wise enough to proceed with a battery of telescopes, pipettes, centrifuges, measuring gages and equations, religion tried to understand the whole workings of the universe with the help of one in-passages obviously demented ancient book.

However, this is to miss that, in truth, religion was never really interested in doing the sort of things science does. It might have thrown off the odd theory about geology, it might occasionally have had things to say about meteorology or aeronautics, but its focus was never substantially on explanations of physical reality. It cared about a mission altogether different and more targeted: it wanted to tell us stories to make life feel more bearable. It was interested in giving us something to hold on to – in the face of terror, shame and regret, when there was panic and grief – that could help us to make it through to the next day. It wanted to offer us ideas with which we might resist the pull of viciousness and self-centeredness, it hoped to encourage us to find perspective and lay a claim to serenity in the face of our too-often impossible and tragic condition.

The defenders of science purported to miss all this, simply framing religion as an entirely flawed pioneering version of physics, chemistry and biology. But from the start of the nineteenth century, prescient observers understood that religion had always been something beside this, that it had taken care of the inner life of humanity and that its retreat would therefore have implications for far more than our grasp of physical reality. Though we might benefit from a hugely enhanced understanding of lightning or the features of the night sky, we might simultaneously be in danger of losing our central resource for coping with the agonies of existence. With only science to hand, what would happen to our need for consolation? What would we do with our nighttime terrors? How could we reconcile ourselves to our mortality? Where would we be able to find peace and a semblance of contentment?

Science largely shrugged its shoulders. This was not its business and nor did these questions seem particularly pressing to many in the field. But others – perhaps more tormented and inwardly fragile – disagreed: they knew that whatever the state of scientific knowledge, humans never lose their need for stories that can make life feel more bearable. It isn’t because we know the boiling point of hydrogen (-252.87 °C) that we promptly shed our appetite for consolation or perspective. It isn’t because we understand the structure of the atom that we have any less of a craving for something mature and psychologically soothing to hold on to in the middle of the night.

For a rare period, this double need – for the consolations once offered by religion and for the truths revealed by science – was artfully held together in a way that it has never quite been before or since. In England during three decades around the middle of the nineteenth century, from a variety of quarters, there were a range of highly suggestive attempts to rope aspects of science into the project of ethical and psychological healing pioneered by religion; projects to mine science for its capacity to do precisely what religion had done so well for centuries: namely guide us towards greater self-acceptance, serenity, forgiveness and peace of mind. Rather than dismissing the central functions of religion, science could – from this vantage point – skilfully and intelligently start to replace them.

The highpoint of this unusual approach was the foundation of two new institutions, Oxford’s University Museum of Natural History in 1860 and London’s Natural History Museum in 1881. Both set out to present the public with the latest discoveries of science: they showed off a treasury of vertebrates and invertebrates, rocks and minerals. There were stuffed bears, foxes and lions, bones of whales and megalosauruses, cabinets of rose-ringed parakeets and birds of paradise. One could peer at the preserved bodies of black seadevil fish and stoplight loosejaws (Malacosteus niger). There were fossilised ammonites and the imprints of brachiopods and 22,000 drawers filled with beetle specimens.

Yet what was evident was that the public wasn’t merely being given a lecture. It was being invited to find inspiration – not unlike the kind one might once have discovered in the annals of religion. The architecture made the concept particularly evident; both institutions looked indistinguishable from churches. Both were in the Romanesque style, with elaborate porticos, knaves and richly patterned columns. Both had high ceilings. In London, one could stand in the center of the main hall, gaze up 52 metres and find, in place of depictions of the Apostles or the Holy Family, 162 panels laying out the earth’s botanical wonders, from lemon trees to date palms, irises to rhododendrons, sunflowers to cotton plants. The first director of the Natural History Museum, Sir Richard Owen, put the mission squarely into view: the museum was to be, in his words, a ‘cathedral’ to science.

Ceiling of the Natural History Museum, London, 1881

Main Hall, Natural History Museum, London 1881

Here too one might pursue consolation, inspiration and perspective. Here too one might shed sorrows and cast aside ingratitude and despondency. The soul of modern man, battered by industrialisation, was being offered a new kind of balm. Science wasn’t dismissing our needs and cravings, our loneliness and fears. It was ready to help with similarly structured, but just more rationally-founded, answers.

The move was tantalising and salutary. But it didn’t – for all the beauty of these early ‘cathedrals’ – catch on. As more science museums were opened, they looked less and less like churches and more and more like regular institutions of learning, the sort of places one might come to if one was considering a career in science or educating a child. For its part, science got on with its day to day task of finding out about the workings of the universe, our planet and all its varied inhabitants. It neglected the business of building any sort of bridge between its discoveries and the spiritual cravings of mankind. As a consequence, the alienation and disenchantment of modern life continued. The more desolate voices complained that though science might have turned out to be ‘true’, its victory had left us inwardly hungry and forlorn.

The despair is unjustified. Science – properly viewed – has never been the enemy of spiritual enrichment. Indeed, when we know how to approach it and are encouraged to do so (whether by architecture or art, literature or film) science will yield ideas every bit as consoling and inspiring, and as applicable to our lives and as relevant to our pains, as those found in religion. The revelations of science do not have to mean an end to the project of therapeutic psychology initiated by religion; they can refashion, enhance and amplify it. This may not be how scientists themselves go about their work or present it to the public, but the fruit of this work lends itself impeccably to a mission of ethical-psychological elaboration.

We can, in other words, usefully look to science for the sort of ideas we used to seek in religion – and which could assuage some the ills of modernity. At least seven big ideas can be found:

I: Perspective – The Scale of the Universe

We are at permanent risk – in the conditions of modern urban life – of losing perspective, that is of making more of our troubles, hopes, fears and status than is warranted or indeed is good for us. One of our greatest terrors is to be made to ‘feel small,’ to be reduced in our eyes by the inconsiderate or thoughtless actions of others. But this is to miss that the solution to our agitation does not lie in expanding our importance, but in learning to reduce it ever further. Peace of mind does not come from finding an indisputable way of enhancing our status, it comes from discovering a sufficiently elevated and distant angle from which to look at everything we are and do in order finally to understand that we are blessedly and thankfully irrelevant to everything.

Humanity used to believe that the earth was at the center of the universe – and that we, in turn, were at the center of creation. Slowly and reluctantly, we came to accept that we might be only one planet among a few others and might be being forced to revolve around our sun rather than it around us.

From there, the progress of science has rendered us ever less significant – with enormous theoretical benefit to our psyches and our impatient and overassertive egos. In 1672, the Italian astronomer Cassini made the first measurement of the distance between two planets – Earth and Mars – and found that the Solar System (still understood as equivalent to ‘the universe’) was an astonishing 20 times larger than the Greek philosophers had thought. Ninety-nine years later, Jérome Lelande accurately estimated the distance between the Earth and the Sun at 93 million miles. In 1838, humanity got an indication of the likely scale of the universe when the German astronomer Freidrich Bessel made the first ever correct measurement of the distance to a star: 10 light years.

We had for a long time imagined that the universe might be a relatively empty place. Around 700 CE, the Dunhuang star chart recorded 1,300 stars seen by Chinese astronomers with the naked eye; John Flamsteed’s 1729 Atlas Coelestis mapped 3,000 stars. By 1903, German astronomers had pushed up the number to 324,000 stars. But only by the 1960s did we become fully aware of the true scale of our puniness. We understood that our galaxy, the Milky Way, has approximately 100 billion stars in it, that there are 10 billion galaxies in the observable universe, each of which contains an average of 100 billion stars, which means that there are around 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (a billion trillion) stars at large.

When we lose perspective, as we invariably do in the course of pretty much every day in the frenetic city, we don’t need a philosophy lesson or a Church service. We need to spend one or two quiet moments with a photograph from the Hubble telescope and a reminder that we are – in a glorious and redemptive way – what we always feared: nothing.

II: All is Vanity – The Second Law of Thermodynamics

Many of our efforts are designed to perpetuate ourselves in time. We strive to live on through our work – and to make something more enduring than our biological selves. To release us from this exhausting and vainglorious folly, religions used to kindly remind us, in the words of Ecclesiastes 1:2, that all is vanity – and they would occasionally show us a skull or shattered tomb to bring the point more forcefully home.

With religion in abeyance, science offers us a yet more powerful expression of this Biblical concept: the Second Law of Thermodynamics. First worked out in the nineteenth century, this states that the tendency of all systems – of which the universe is one – will be to dissipate energy over time until it reaches a state of total rest. Given a sufficient span, estimated as 10106 years, our universe and its superclusters of galaxies will all collapse and we will enter what scientists call a Dark Era, in which – after so much excitement, individual and cosmic – nothing will remain except for a quiet dilute gas of photons and leptons

The situation is no better closer to home. The sun’s centre burns, like a giant engine, at 15 million degrees celsius. But our Sun is 4.5 billion years old and the average stable lifespan of a star is a mere 8 billion years. An added complication is that the Sun’s brightness increases by 10 per cent every billion years, gradually heating our planet. In 1 billion years, the sun’s increased brightness will have caused our oceans to evaporate and made all life impossible. In about 4 billion years, when it runs out of hydrogen, the Sun will become a ‘red giant’ star, possibly expanding as far as Mars, at which point it will absorb and destroy Earth. The outer layers will drift into space to form a planetary nebula. The remaining core will be a dense, stable ‘white dwarf’ that will continue to radiate heat for two or three billions of years.

If one needed to repeat the point with NASA’s help: all is vanity.

III: The Resilience of Life – 5 Mass Extinctions

It can be easy to fall into worry about whether we, and most of what matters to us, will endure. The kindest advice is not to imply that all is assured and that a cataclysm can be averted; it’s to understand how common wholesale destruction has been on our planet and to be cheered by the thought that, nevertheless, life has endured, for it is ultimately a far more tenacious process than any cellular being in which it happens to subsist at a specific point. Individuals and species may die; life itself survives (at least until the sun burns out). We are standing on the petrified remains and fossilised bodies of thousands of species which came before us. By extension, many more will come after us. From a sufficient distance, we are not the end point and therefore should not cling so anxiously to what presently exists. We should learn to identify with the long-term direction of the river, and not grasp so tightly to our own fragile vessels bobbing unsteadily in the turbulent eddies of the present.

There have been five mass extinctions afflicting multicellular life in the last 540 million years. Earth is a risky place and has always been so. We’re not living in especially tempestuous times; peace is just an illusory byproduct of short-term thinking. 450 million years ago, the Ordovician mass extinction, caused by a mini-ice age, caused the planet to lose 70% of all its species, including most trilobites, brachiopods, crinoids and graptolites. 375 million years ago, another 70% of species were lost in the Devonian extinction. In the huge Permian extinction 252 million years ago, 95 percent of marine and 70 percent of terrestrial species vanished (among them the fin-backed reptiles called pelycosaurs and the vast mammal-like creatures known as moschops). But life went on – as it always does. Gradually cellular existence built itself up again and a semblance of serenity appeared to reign on earth. But naturally that was an illusion too and 201 million years ago came the Triassic extinction (triggered by the breakup of the supercontinent Pangea) and in the process, gone were the brachiopods, the shelled cephalopods, and the phytosaurs. Lastly and most famously came the Cretaceous extinction, 65.5 million years ago, which did away with the dinosaurs, the flying pterosaurs, the mosasaurs, the plesiosaurs and the graceful ichthyosaurs.

Not to put too fine a point on it, we should not expect our particular life form to endure. We are writing in time in fading ink. We will eventually go, but life itself will stubbornly persevere: within a few hundred million years, a creature comparable to us, but perhaps a little kinder and a lot more intelligent, may replace us and will spend weekends looking at our remains with a mixture of pity and boredom in the display cabinets of a new generation of scientific cathedrals.

IV. Forgiveness – Evolution

It’s deeply tempting to lose our temper with ourselves and our fellow humans: why can we not be more reasonable? Why are we so prejudiced? Why do we worry so much what other people think? Why are we so prone to anxiety? Why do we eat so much? Why are we so interested in pornography?

It’s equally tempting to search for explanations that emphasise our villainous natures and then to harshly condemn our lack of self-command. We end up disgusted with ourselves and intemperate and judgemental towards others.

But science – far more effectively than religion – may teach us the art of forgiveness, and liberate us from our urge to criticise. Of course, we are less than ideally adapted to the civilised and intellectually complex lives we aspire to lead. Of course we are largely demented, prey to powerful impulses, filled with dread and driven by lower appetites. We have had very very little time to do or be anything else.

We are estimated to have appeared in more or less our current form in Africa 200,000 years ago. For most of this time, we lived in small groups, we foraged, we grunted, we didn’t wait for others to stop talking, we fought constantly, we were terrified of everything and understood almost nothing, we didn’t sit quietly in chairs for many hours, we didn’t wear tight fitting clothes, we couldn’t read or write, we got very interested in any fertile human who came our way and we gorged ourselves whenever we found something sweet growing on a tree.

The time since the birth of Jesus comprises 1% of our history; the last 250 years, the period since we became urbanised and began living with technology in scientific culture encompasses a mere 0.1%. Naturally, therefore, most of our impulses are askew and better suited to more basic conditions. It’s a miracle we ever manage to be polite, to explain our feelings, to compromise and to see it from another’s point of view.

We are – from the vantage point of science – doing extremely well indeed. So much of our capacity for calm depends on our sense of what people should be like – and how well they succeed in measuring up to prior expectations. Given our evolutionary history, humans should be a lot worse than they are. Humanity is rushing to catch up with its ideals and we can afford to be gentle towards its constant but inevitable lapses. The wonder isn’t that we’re so uncivilised but that we ever even manage, now and then, to have a few moments of civilisation.

V: Beyond the Ego – Mind and Body

The human animal is a proud creature. We puff ourselves up, we exaggerate our competence and integrity. We imagine ourselves enduring. At the heart of our misplaced assurance is a particular concept of the self. We imagine it as an integrated ego that can understand most of what it is, that is radically separate from the world beyond – and that may have an immaterial essence that will endure after the body has expired.

Science flatly contradicts us on all such assumptions. The ego emerges from its analyses as something far closer to what Buddhism has long suggested: an artful illusion, a flickering unsteady flame unaware of most of what it is, an entity thoroughly merged with and traversed by the world beyond it, an ‘I’ bathed in otherness destined to dissolve after a brief span and to be reabsorbed by a cosmic totality from which it should never have imagined itself to be distinct.

To listen to the neuroscientists, our impression of being a coherent ‘I’ is only a clever trick performed by a narrative capacity lodged somewhere within the cerebral cortex, and which weaves our scattered memories and intermittent sensations together into an ongoing sense of being someone in particular – rather that just a rough assemblance of random impressions, pain and pleasure signals and conflicting wishes. Our conscious awareness compromises only a fraction, as little as 5%, of our overall cognitive activity. Most of what we do in our brains is housed in faculties from which our day to day understanding has been barred; we both somewhere know and yet actively don’t know how to make our hearts beat, grow fingernails, digest sugar, walk up the stairs and extract oxygen from the air. We don’t have the keys to our own house. Rather than one unitary brain, we are an assemblage of different brains that evolved in separate millenia, each with its own set of priorities and agendas kept private from our pilot selves; the cerebellum wanting one thing, the hippocampus another, the medulla a third. The sense of being ‘a person’ is a simplification kindly designed to keep us steady, and whose invented nature we sometimes get a sense of as we fall asleep or when we are discombobulated by illness or start to be fragmented by age.

As evidence of how much otherness we bear within us, we need only consider that our gut is host to over 10,000 alien microbial species, single-celled eukaryotes as well as helminth parasites and viruses, that entered our bodies in the early years of life (as we licked the carpet or kissed our parents) and that now help us to digest dietary fibre or synthesize vitamins B and K. How quiet we tend to keep, when introducing ourselves to someone else with the use of a single name, about the symbiotic relationship we are currently conducting with trillions of wholly foreign bacterial cells pullulating within us a few millimetres from our waist band.

As for our sense of being continuous, this too has little basis in our biology. We may think of ourselves as a unitary person who survives through time but pieces of us are constantly dying and being remade. 30,000 cells are lost every minute; the average cell is seven years old. Our external surface layer is replaced once a year; every decade, our whole skeleton is remade, every two years, our liver is fashioned anew. We’re not so much a person as an instruction manual for a person who keeps dissolving and having to be laboriously put back together again.

At our deaths, the fictional nature of our egos can no longer be denied, our sixty trillion cells become a feast for maggots, bacteria and fungi. A part of us will end up in the stomach of a beetle. A slug will feast on a part of our liver. A bit of us will provide a nutrient for a hawk. The carbon in our bones will end up inside the trunk of a conifer tree. Some of us will come down as rain. We were never really an ‘I’; we just borrowed some bits of the universe for a few moments and will go on to be many other things, just as valuable, in time. Like every living thing, we were made from tiny shards of stars; we have travelled through supernovas. We’re as old as the universe; ‘I’ was just a passing phase. What was lent to us by the earth will animate new life in time.

None of this should panic us. Scientific reality may inspire a far more consoling philosophy than any book of prayer. We don’t need to clasp so tightly onto life. We are never quite whole and will soon enough be in pieces again. There is no use expecting to be remembered by the name our parents thoughtfully gave to a small assemblage of cells – all now long dead – many years ago. The woodlice and the pigeons will be grateful. We aren’t strangers to death: section by section, we’ve been falling apart and being remade for just over 13 billion years.

VI: Scepticism – Sensory Frailty

Though we may strive to look powerful and to be in the know, to impress and to dominate, in truth we are at our most endearing when we are strong enough to reveal our vulnerability – when we can admit to all we don’t understand and are blind to.

Aspects of science work to make us more human in this regard because they constantly enforce the message that we are fragile and easily-confused beings who have no option but to misunderstand most of what is going on around them.

Our touching humanity is nowhere more evident than when we consider, through the perspective of science, the unreliability of our senses. We may think we know what is happening in the world, and for centuries we were very sure indeed of our verdicts, but modern science has served to reveal the scale of our day to day ignorance.

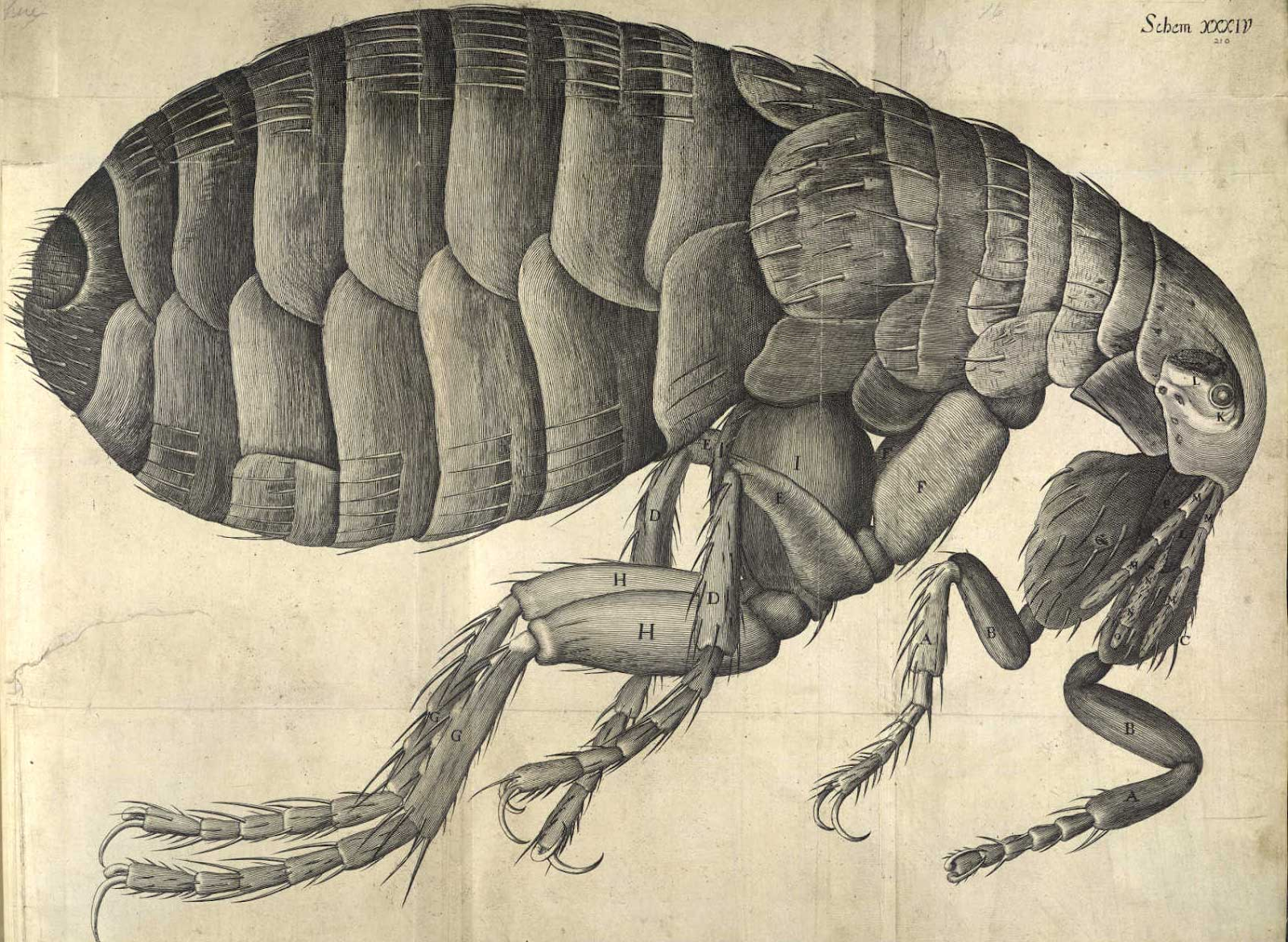

We might be inclined blithely to trust our eyes – but how little of what exists is ever natively captured by them. Only a narrow band of electromagnetic waves ever registers on our retinas. We miss infrared light at one end of the spectrum and X-ray light at another. For most of history, we couldn’t guess what a fearsome and noble creature a flea might be, until in 1665, the scientist Robert Hooke showed us one from under his microscope at two hundred times its real size.

Robert Hooke, A Flea, from Micrographia, 1665

We miss that a single drop of seawater – casually tossed off our bodies after a dip – might contain 10 million viruses, a million bacteria and a thousand small protozoans and algae – among these the cyanobacteria prochlorococcus, 0.6 micrometres long, collectively responsible (there are 3 octillion of them in all) for releasing 20 per cent of the oxygen in the atmosphere.

A drop of seawater magnified x25, showing tiny crustaceans, larvae, plankton, worms, fish eggs and brown-gold coils of cyanobacteria, one of the oldest life forms on Earth.

On a clear day we can see objects 5 kilometres away at best – which is why it has been conceptually so hard for us to grasp that Proxima Centauri, our nearest star, might be 39,900,000,000,000 kilometers from us – just as it has been hard for us to imagine that there really could be 43 quintillion atoms in a grain of sand, each like a miniature planetary system, with electrons orbiting a nucleus of protons and neutrons, inside of which dwell smaller hadrons, inside of which reside even smaller quarks.

We trust our ears and fail to realise that there is no such thing as silence, just the limitations of what we can hear. We only register sounds between 20Hz and 20,000Hz and so miss all that is above (infrasound) and below (ultrasound). We can’t detect the sounds of the Sumatran rhinoceros (3 Hz) or of air passing over the tops of mountains. We miss the noise emitted by lightning above us and by the harmonic tremor of pressurised magma deep in the earth below us. ·

Likewise, our understanding of time, anchored as it is within units of 24 hour days and the year it takes for the earth to orbit the sun, starts to collapse when asked to comprehend that it might have taken 250,000 generations – or a quarter of a million years – of genetic mutation for vertebrates to generate their eyes or that it’s been a mere 84 generations since Julius Caesar walked the earth 2,000 years ago.

Only 5 per cent of what we call the observable universe is in fact ever captured by our senses. We depend on clever theories for the other 95 per cent.

We are – unaided – humblingly out of touch with, and perplexed by, pretty much everything occurring around us. We should go easy on ourselves.

VII: Our Existence – Cosmic Gratitude

It may not at first glance be entirely evident how a discipline as reserved and sober as science could lead us to an intense appreciation of all that is good in our lives and a wonder at the benevolence and beauty of our surroundings. But it turns out that science is supremely capable of nurturing feelings of gratitude because of a basic truth about the way gratitude works: that it arises from a sense of contrast, from an awareness of how much more awful things might have been, of how dreadful things can get – and of how lucky, all things considered, we have turned out to be.

There are, naturally, a million things that we have missed out on and areas of pain that continue to scar us, but science bids us to look up and at points remember some of the larger reasons we possess to be thankful. When our psyches allow us a moment of respite, we can be grateful:

– that 13.8 billion years ago, something smaller than an electron chose to swell within a fraction of a second like an expanding balloon into a zone permeated with energy 93 billion light years in size that we now clumsily call the universe

– That some of the energy from this swift expansion was able to coagulate into particles, which grouped together to form the light atoms of hydrogen, lithium and helium – which then assembled into galaxies, which gave birth to stars, inside whose molten burning cores all the elements necessary for the nucleic acids essential to life – carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, sulphur and phosphorus – were forged.

– That gravity drew the stars together to create galaxies (a hundred billion of them), including – fortuitously – the Milky Way, a small corner of the universe containing just 400 billion stars, in which our sun was born out of a giant, spinning cloud of dust and gas 4.5 billion years ago.

– That around the same time, swarms of debris collided to form our Earth – a lava-washed, uninhabitable rock, that gravity happened to throw into orbit as the third planet from the Sun – the exact right distance away (0.38 to 10.0 astronomical units) for life to develop.

– That another planet, Theia, collided with Earth, gifting us our Moon, which slowed the Earth’s rotation, stabilised atmospheric conditions and created the 24-hour day and caused the Earth to tilt, forming the seasons, without which we would have permanent regional extremes of heat and cold, drought and floods.

– That ice particles leftover from the collisions of hundreds of comets melted, water vapour condensed and oceans were formed.

– That comet collisions delivered another chance cosmic gift, the essential components of life and DNA like ribose, carbon dioxide, ethanol, amino acids and phosphorus.

– That underwater hot springs released the right amount of energy and the right mix of chemicals to allow the first single-cell organisms, prokaryotes, to form four billion years ago.

– That Earth’s toxic atmosphere of methane and carbon dioxide slowly became sweetened by the release of oxygen from cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) – the first creatures to photosynthesise – and gradually oxygenated 85% of the atmosphere.

– That 2.7 billion years ago, a random, chance event known as ‘the fateful encounter’ meant that two single cells merged, and procreated and then after about a billion more years, developed sexes.

– That 500 million years ago, plants – at first algae and lichen – spread from the oceans to the land before animals did and slowly developed into more complex vascular plants, whose seeds could be dispersed by wind, creating the grasslands and forests in which different species could evolve.

– That 245 million years ago, a rise in oxygen levels led to the Cambrian explosion, which saw the greatest diversification of life in Earth’s history, starting with ocean-dwelling hard-shelled invertebrates, leading to new fish species, the first land-based insects and large vertebrate ocean animals that developed four limbs and went ashore to lay eggs – which hatched and evolved into amphibians, reptiles and later mammals.

– That an asteroid 15 kilometres wide happened to hit Earth 65.5 million years ago and destroyed most terrestrial organisms including all non-avian dinosaurs, but created ideal conditions in which some small, furry mammals, our close ancestors, were able to thrive with less competition and evolve into primates.

– That the Earth remained stable enough for long enough that the first apes could appear in Africa, 25 million years ago, the first hominids 7 million years ago and our frightened clever brilliant homo sapiens a mere 200,000 years ago.

– That your genes managed to pass safely through an unbroken 10,000 generation chain, despite the best efforts of cyclones, predators and a constant barrage of viruses.

– That an average, fertile woman will have 100,000 eggs, and a man will produce a trillion sperm, each of these very different, but that – nevertheless – you have have managed to emerge from the options as you are.

– That there are days of balmy sunshine and lemons, that there are olives, figs and hazelnuts.

– That this moment exists within a 13.799±0.021 billion year span of cosmic time.

And to all this, as they used to in the churches, one might cry (or whisper): Hallelujah!

***

There is enough in science to give birth to twenty religions – so much to worship, to be awed by and to be consoled through. How poor the old religions were by comparison, how paltry an invention a god is next to the mysterium tremendum of dark matter, string theory or quantum wavefunctions. The curse of modernity is not to have invented science; it’s not yet to have understood all that one might do with it.