Sociability • Communication

How to Be a Good Teacher

In theory, we respect teachers. But being a teacher isn’t glamorous. It’s a worthy – but slightly dull – profession. Our suspicions are encapsulated in our collective image of the teacher with the 1950s jacket.

Because we associate teachers so strongly with schools, it’s natural to assume somewhere in our minds that ‘teaching’ is something most people leave behind as they grow up. We tell ourselves that it takes a very special type of person to be a teacher – and assume that we’re just not cut out for that kind of role.

But in truth, being a teacher is one of the most central aspects of human life. Even if we don’t sign up to instruct adolescents in chemistry or history in a school, we will have to become teachers. There is no alternative but to master the art of teaching. Teaching just means getting an insight, emotion, state of mind or a skill from your head into the head of someone else. Teaching happens every hour of every waking day. But we’ve fatally misconstrued teaching as a specific professional job, when it’s in actuality a role that everyone has to dip into continually. Whether we like it or not, we’re very frequently required to teach.

Being a good teacher is fundamental in the following areas:

a) Relationships

Troubles in relationships are almost always, at heart, related to poor teaching. There are things in our heads we can’t get across and things in theirs we can’t grasp. Misunderstandings abound and fury and resentment rises. The flashpoints come:

Around sex: There’s something you’d really like to do in bed with your partner; but you’re very nervous about how they might respond. The tendency is to feel it’s hopeless. Or to get insistent – which turns your partner off. This is really a teaching issue: we tend not to think of the situation as one where education, and therefore teaching, is the key concern. But that would actually be a more accurate and helpful frame. We don’t say: hold on, can I teach you a short course on attitudes to cunnilingus? But that’s actually what we should be doing.

Napoleon didn’t teach Josephine about his sexual needs

Sharing a problem one is having at work: you’d love to have your partner’s sympathy; but they’d need to understand quite a bit about the situation at work: why the strategy you’ve been pursuing doesn’t seem to be working, but is actually a good idea; why a certain colleague’s support turns out to be worse than their hostility; why the situation in Mexico matters so much. But getting them up to speed on all this is so hard, you want them just to understand already.

Conveying your gripes: you get enraged by things like the way your partner stacks the dishwasher; by how they close the cupboard door in the bathroom; by their over-confidence about getting to the airport on time. Again, we don’t naturally think of it in these terms, but what’s at stake is teaching: you ideally want to teach your partner how to close the cupboard door, how to load the machine, how to catch a plane.

Who you are: a huge underlying educational theme of relationships is teaching your partner about yourself. It’s a matter of trying to get them to understand the nature of the person they’ve got together with. The fact that – for you – certain things are extremely difficult which others take in their stride. Maybe you find filling in forms unbelievably challenging – not because you are lazy or irresponsible. But because form-filling was always your father’s thing and he made it seem terrifying and dangerous, it was something only he could do.

In love, we might – for example – find it very hard to teach each other the difference between rejection and the need for solitude

Or perhaps you really need to spend quite a lot of time alone not because you want to reject your partner, though that’s how they see it, if they don’t understand you properly; in fact it’s because there’s such a lot of things going on in your head that you need time with very low input to try to calm down. Ultimately, it can seem a mystery why you are the way you are. But the more careful explanation is often much less alarming that the worried constructions other people are liable to put on things.

Walt Whitman: like all of us: I contain multitudes

There’s so much that we never get around to communicating about ourselves – just what a particular piece of music means to us; why the holiday in Devon when you were fourteen was so memorable; why you like tidying the sock drawer… which counters the tendency in relationships for people to fall into quite narrowly-defined roles. Like the US poet Walt Whitman, we ‘contain multitudes’ – aspects of ourselves that might be endearing and interesting, but which we tend not to get round to teaching other people about.

b) Parenting

Chardin: a lesson in how to have lunch

Parenting is an almost endless sequence of teaching tasks. One might be trying to get one’s child to understand: how to butter a piece of toast, how to avoid escalating a row; how to brush their teeth; how it’s possible to love someone and be angry with them at the same time; how tidying up can be fun; how money is important, yet not an accurate measure of worth; how to put up a tent; what your experience has taught you about the transport industry; what it is to be a friend …

We want to download as much of our accumulated wisdom as we possibly can; but doing so is a hugely tricky operation, requiring the best teaching skills. We mostly fluff it, partly because we’re not alive to the enormity of the pedagogical task.

c) Work

Businesses are places that burden us with huge teaching requirements.

Giving feedback is really teaching – though we don’t happen to call it that and so we don’t so easily recognise the true nature of the situation. You are trying to get the person to understand why something matters more than they suppose; or why this way of going about solving a problem is better; or how to know the difference between asking for help when you need it and being too needy and dependent.

Also, in most meetings, there are teaching tasks circulating: I need to teach you about this staffing problem; I need to teach your about the legal perspective; or why this hold up is occurring and why it can’t be solved the way you think it can. If the teaching is done well, there’s a huge potential gain. We tend not to see these as teaching tasks (with much in common with teaching a child how to find the area of a circle or ask for a train ticket in French) so we typically approach them without due respect for the difficulty of the task.

d) Friendship

It’s natural to overlook the role of teaching in friendship, because friendship so often originates in a shared outlook. Yet, to be a true friend doesn’t involve formal lessons but it frequently entails teaching: trying to get your friend to see why a course of action they are keen on is not such a good idea; why they should worry less about one problem – and more about another. Wanting to teach a friend isn’t a mark of being patronising. It’s a desire to guide them to bits of the truth they may not yet have spotted.

e) Politics

Essentially politicians are in the business of teaching societies their ideas about matters of major collective importance: what a good economy is; how to view certain troubling sectors of society (the very rich, the very poor, the very different); what can be changed and what has to be put up with; what’s a realistic aspiration and when potentially dangerous overreach kicks in. We could gauge the health of a political system by asking: how good are the political leaders at teaching?

So this is a list of some of the things you’ll need to do to be a good teacher:

1. Have confidence in the business of teaching

Generally we are the inheritors of a Romantic tradition that constantly tells us not to teach and instead to be enthusiastic about spontaneous, intuitive responses (go with your gut, listen to your heart). Our age is negative about the idea of teaching – outside of obviously technical fields. We understand there needs to be teaching when it comes to learning to ski or work out the area of an isosceles triangle. But we’re often quite resistant to the idea of ‘teaching’ around the core issues of human existence – who should one marry, what is beautiful or ugly, what the media is for, what cities should look like – we turn against the idea that there can be teachers, because we’re collectively inclined to the Romantic notion that these topics are purely personal and that wisdom can’t be transmitted. So no one has any right to teach. No one should be in a position of authority. We often bristle if someone tries to tell us what to do or how to think. We’re suspicious of the notion of authority in such areas and hence reluctant to see anyone as entitled to teach.

It is a kind of healthy democratic headwind against which any desire to teach (to get others to learn from you) has to contend.

What we need to burn into our souls is the idea that – all the same – it is actually perfectly legitimate and reasonable to try to teach. Everyone has a lot to learn and everyone has something important to impart to others. We should also be deeply aligned with the approach of classical culture: seeing most human activities are areas where learning and teaching are possible and important. In the classical view of things, we can learn (via the teaching of others) how to be kind, how to be funny, how to be better at being married or single, how to run a country or write a successful tragic play.

That is why we should remind ourselves just how deeply legitimate the idea of teaching is.

2. Admit that learning can be boring

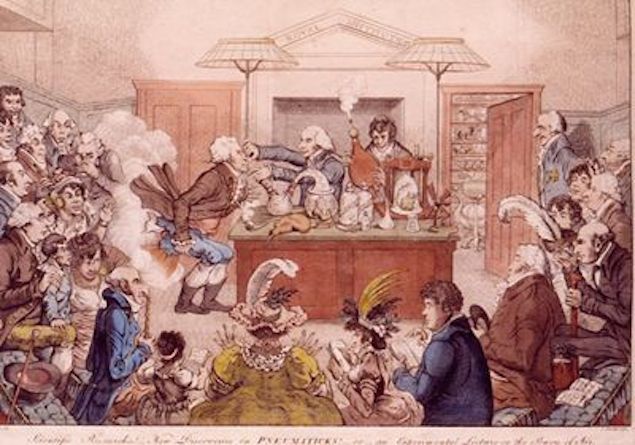

One of the best teachers of the 19th century was scientist and educator Sir Humphry Davy. He was a very successful researcher in his own right: he discovered chlorine and invented a special kind of safety lamp for use in coal mines. He gave public lectures that were wildly popular, even though they dealt with abstruse and complex scientific topics.

Davy filled his lectures with explosions and comic effects (he loved laughing gas); he made witty remarks.

He wasn’t simply being amusing. He was using fun to help him transmit serious ideas he was hugely committed to. He understood that an overwhelming obstacle to learning is boredom. If we get bored, we stop learning. Instead of getting sniffy about this and blaming people for being so feeble and lacking in the bole thirst for knowledge at any cost, Davy simply accepted it as a fact about the human mind and made sure his audiences never failed to learn for that reason.

He was free of a fatal confusion of ideas which tempts those teaching to think that if what they have to say is important they must present it in a solemn manner. They feel that humour is unworthy of the dignity of the topic. But sadly that often just means that important things don’t get the recognition they deserve.

3. Understand – and disarm – the fear that learning this ‘isn’t for me’

Elizabeth David was one of the great cookery writers of the twentieth century. But for quite a lot of people she was – despite her best intentions – an actual obstacle to learning to cook. Elizabeth David gave the impression that being interested in cooking was only for people like her: female and rather refined. She could say: ‘everyone can learn to cook’ – but the words alone are not enough to get over this kind of resistance.

Technically, Jamie Oliver is as serious and knowledgeable about cuisine as Elizabeth David was (and he’s often said how much he’s learnt from her.) But he developed a major teaching strategy. To overcome the fear that cooking might be a bit too fiddly and a little too posh, he made huge strategic use of his own blokey, down-to-earth tendencies. He was, in effect, holding himself up as living disproof of a natural (but mistaken) fear: the fear that people like me can’t learn this stuff.

A lot of teaching goes wrong because of a background belief in the student that something they are is incompatible with a lesson. There’s a feeling that I can’t be who I am – the person I’ve always been, that my friends know me for, who I am comfortable with – AND get involved in knowing this new thing.

Pretty much everyone has some version of this. We might feel that we can’t learn coal-mining and be feminine. We might feel we can’t be really interested in making money and pay attention to the views of Karl Marx. Or that we can’t be interested in a fair, more equal society and get interested in 18th-century classical architecture. Or it can feel very awkward to like rough sex and be respectable; read Proust and play football; know engineering and be a feminine woman; be a great worker and make mistakes.

The good teacher disarms these fears as much as possible – and the simplest, ideal way is to authentically and cheerfully embody the combination that’s supposed to be impossible.

4. Don’t seem High & Mighty

Instinctively, we often suppose that what we say will be more authoritative and carry more weight if we can present ourselves as pretty much perfect. If you don’t make mistakes, you are going to seem right. Unfortunately, however, this attitude is very rarely shared by anyone who is on the learning side of the equation.

Yes, we want to be reassured that the person doing the teaching knows what they are talking about in this particular instance. But the potential for the humiliation of the one learning is never far from the surface. We easily resent being taught. We easily feel that the one doing the teaching is showing off. All this might be very untrue in fact. But it’s the fact that we feel it that creates the obstacle to learning. Being taught places the student in a position (however momentary) of inferiority. You have something, they don’t.

So if you’re teaching, it’s tremendously useful to surround any ‘lesson’ with active reassurance that you are on the same level basically – this lesson aside. Show that you too have faults, are often clumsy and goofy. Show that you too don’t know many things. You need to show areas of inferiority so that your own superiority in the teaching area won’t stick out and offend.

5. Don’t blame the learner for not knowing

It seems paradoxical – once it is pointed out. But the fact is we often get very annoyed that someone doesn’t know something yet – and we assume they should, given who they are, at this point in their life, with their track-record… And so we go about the business of teaching them with a background grudge; we feel it’s their fault; they don’t know so they must be stupid, lazy or in some way inadequate. And this attitude makes it unlikely that what we have to teach will actually make its way successfully into this person’s head.

A lot of good teaching starts with the idea that ignorance is not a defect of the individual: it’s the consequence of never having been properly taught – however old one or ostensibly ‘educated’ one happens to be. So the fault, rightly, really belongs with other people who haven’t done enough to get the needed ideas into this individual’s head or simply with the brute fact of belonging to our deeply flawed species.

6. Pick your moment

Being in the right mood is a huge factor in how well we learn. We instinctively recognise this about ourselves. We feel too tired, too bothered about other things, too excited to take in anything tricky or serious. But it’s much harder to acknowledge this fact when it comes to other people.

We tend automatically to try to teach the lesson at the moment the problem arises, rather than selecting the moment when it is most likely to be attended to properly.

Mood is also crucial to how well we can teach, the more desperate you feel inside, the less likely you are to get through effectively. Unfortunately, we typically end up addressing the most delicate and complex teaching tasks just when we feel most irritated and distressed.

There’s a panicked feeling that if I don’t jump on this right now it’s going to go on and on unchecked forever. Picking one’s moment means being very sure that you can avoid tackling something right now because you are determined to address it more effectively later on.

Being skilled at timing has often been recognised as a major virtue and accorded high prestige – in the history of warfare, for instance. In 9 AD Germanic tribes won a major victory over the Roman legions. The less well equipped German tribesmen won because they chose their moment well – when the legions were passing through a thickly-wooded region and couldn’t form up in their accustomed order. Up until then, the Roman generals had assumed that the Germanic tribes would be unable to pick their moments wisely, but would always get so enraged by the sight of the enemy that they would attack on impulse.

By picking their moment, the fortunes of the Germanic tribes were transformed. Given how central teaching really is to our lives, and how much opportunity is squandered by poor timing, it’s strangely sad that we haven’t as yet developed a cult of great timing in addressing tricky matters in relationships or at work, passing down the stories from generation to generation of how, after years of getting nowhere with impulse-driven frontal assaults, she stood patiently by the dishwasher, waiting until she had put down the newspaper, and then carefully advanced her long prepared point, and eventually won a decisive teaching victory.

7. Simplify

When we’re familiar with something – which is a prerequisite for teaching – we’ve got a fatal tendency to forget how immensely confusion and challenging new things can be. So when we try to teach we launch into too much detail, we point out refinements before the person we are talking to has mastered the basics. In short, we forget what it was like not to know.

Simplification can sound a bit condescending. Because we’ve unfortunately come to assume that being complicated is pretty much the same as being intelligent. And we see simplification as the wilful ignoring of the more complex issues.

But there’s another way of looking at this. In fact, we almost never in practice use very complex ideas. We always work with boiled-down, clearer more basic ideas. Getting to these is the real goal.

We should take to heart Wittgenstein’s assertion:

Everything that can be said, can be said clearly.

8. Coat it in sugar

Acquiring knowledge can be bitter. The church of the fourteen helpers in Bavaria was built about two hundred and fifty years ago. Strange as it might sound, the ideas that led to its construction are deeply important to the business of teaching. At that time, the Catholic Church wanted to enforce a specific moral. They wanted to say that everyday compassion and care, however humble and ordinary it might look from the outside, is hugely important. The Church wanted to make this message more active in people’s lives, edging us away from our natural selfishness and busy indifference. They had a key idea about something important and wanted to bring more people on board.

The carrot

They were also keen to avoid a technique which they’d been trying for centuries and that hadn’t worked so well: that of terrifying and guilt-tripping people into being good. So, in this part of Southern Germany, for a time at least, they settled on a different, much more intelligent technique. They weren’t going to talk about hell and damnation any more, they were going to try to seduce people into being good.

The stick

The Bavarian church is important to teaching because it explores a very different approach. It doesn’t nag, it does not issue stern warnings or upbraid us for being selfish. It does not make us feel guilty about our failings.

Instead the architect used every possible means to persuade people through excitement, pleasure, awe and delight. The interlocking domes and vaults are exceptionally beautiful – inducing a mood of lightness and vitality. It is splendid – but for a reason. It is expressing the true glory of modest goodwill. It wants to seduce us, charm us, into kindness. It acknowledges we might need a lot of encouragement.

There is a big lesson here for teachers. There are so many serious things we need collective persuading about. The rich need to be persuaded to be much more generous than they are currently being, bankers need to be encouraged to be more prudent around money, we should be more cautious about damaging the environment, more considered about what we eat and nicer to our children. Good ideas about all of these matters are very prominent already. But teaching too often attempts to motivate us by guilt, rather than charm us into goodness.

***

Some of the most difficult moments in life are in essence failed teaching moments:

Losing one’s temper:

The person who is shouting – who has lost their temper – was trying to get a point across. Feeling unable to do so in quieter ways – but desperate to be understood – they start shouting, swearing and stamping their feet. If we could carefully unravel their intentions, we’d see that they are trying to teach the person they are angry with (get them to see things in a particular way, to admit a fact).

Withdrawing: going cold and silent:

The feeling that the other person ought to know, can inspire a refusal to teach. I want you to understand but I’m so angry that you don’t already that I will refuse to try.

Contempt:

The other person is an idiot: they don’t know and won’t learn. Current ignorance is seen as a reason not to teach.

Shyness: lack of confidence:

Teaching doesn’t feel legitimate. You fear that others won’t listen; they might get annoyed with you, make you feel ashamed.

Embarrassment, humiliation:

One feels so confused about what one’s trying to say. One has a go, but it feels boring, over serious, unduly harsh. The person you are speaking to loses interest, of course. You feel a failure.

Despair:

But probably the biggest failure of teaching is when one gives up: you are lost for words, you don’t know where to start, you feel too awkward and nervous, too shy. The possibility of ever really getting the other person to understand fades away. It stops even occurring to you that you could teach them and change their way of thinking. This is expressed as sullenness: where one has come to feel that there’s no point in even trying to explain.

Conclusion

We have to teach all the time; but teaching is hard. Every day you’re called upon to perform these educational moves – at work, at home, with friends – without ever having signed up to the task. You didn’t ask to be a teacher.

The topics might be quite dissimilar – a lesson on how to put the butter back, how to code a piece of the website, how to cope with rejection – but they share many similar features. And they all boil down to the same core: how do you overcome the obstacles to getting what you understand into someone else’s head?

Our society hasn’t as yet fully taken on board the scale of the challenge. So we don’t as yet have in place an educational system that assumes everyone is going to have to get good at teaching.

But it would be unfair to place the responsibility solely on the idea of teaching. There’s also the parallel, universal role of being the student. We all have to accept that other people have the right to try to teach us things (that we’re far from perfect) – and that they may be trying to teach us something very valuable, even if they’re making a complete mess of it. We must forgive the unskilled teacher, there may be a grain of truth beneath some blundering efforts.

When someone is doing the teaching process badly, it’s unfortunately natural to assume that they don’t have anything to teach. And that what they are trying to get across is wrong. If you’re being boringly nagged about not eating enough broccoli or about the importance of checking the window locks before going out, it’s deeply tempting to reject not just the annoying way you’re being told, but also the validity of what you are being nagged about. We don’t just feel like shooting the messenger. We also want to shoot the message.

The core point is taking seriously the idea that we’ve still got a lot to learn from other people and that being a student is a skill – even if the teacher isn’t up to scratch we can still extract a benefit from what they know that we don’t.

There’s a hopeful side to all this. We’re not as yet generally focused on learning how to teach; but it’s not a huge mystery. We already know collectively a lot about good teaching: we’re just not ambitious enough about deploying this knowledge very widely. We’ve seen teaching as a specialist professional skill that only a few people need to master. In fact, we’ve all got to get better at it in order to have somewhat less fractious lives.