Self-Knowledge • Fulfilment

How to Become a Better Person

Why does being ‘a good person’ have such a bad name? In the modern world, the idea of trying to be good or kind conjures up all sorts of negative associations: of piety, solemnity, bloodlessness and sexual renunciation. It’s telling that ‘wicked’ has even become a term of praise.

And yet the project of being good is as vital, or even more important, for the individual and society as is the project of being healthy. Yet while we have no problem with going to the gym to get fitter, it sounds deeply weird, even creepy, to suggest that one might ‘work’ at being better or nicer.

That’s because we imagine that practice has nothing to do with being good – and if it is involved, then it’s merely a route to being fake. We assume you just are good (or are not) but exercise is not involved. This seems profoundly mistaken. Just as we have physical muscles, so we have ethical ones, and they too must be put through their paces. Goodness has to be worked at.

In the ethical gym of the future, we might regularly be put through our paces. We would have to imagine life through another’s eyes, practice giving way in arguments, emulate the diplomacy and tact of paragons of patience and learn to deflect despair through calculated doses of hope.

Aristotle thought that being good meant practising twelve key virtues, Christianity argued for seven.

There’s no scientific answer, but the key seems to be to have some kind of list with which to guide our efforts at being good. We all want better lives, until now, too few of us have shown much interest in being better people.

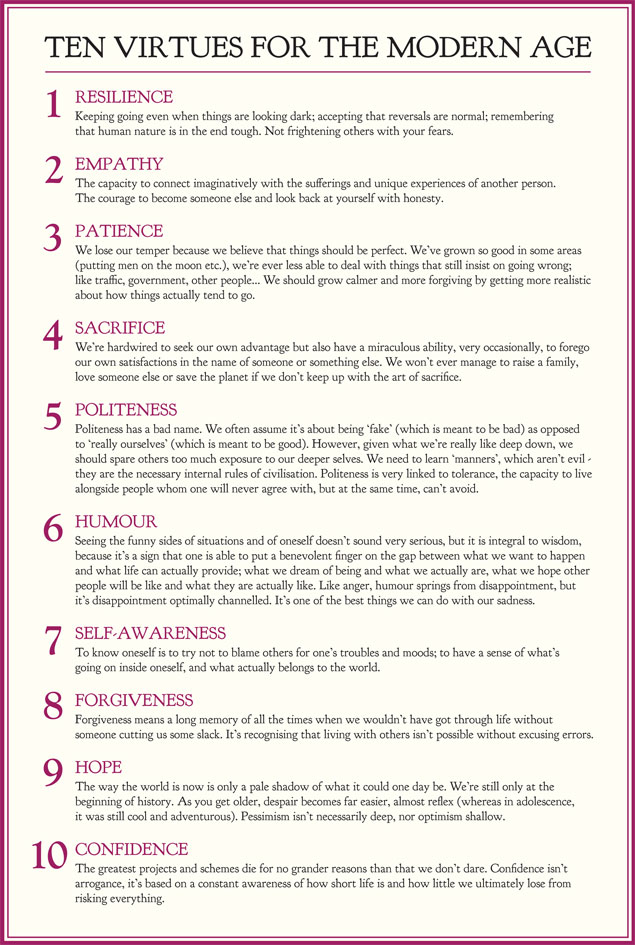

TEN VIRTUES FOR THE MODERN AGE:

Resilience: Keeping going even when things are looking dark; accepting that reversals are normal; remembering that human nature is in the end tough. Not frightening others with your fears.

Empathy: The capacity to connect imaginatively with the sufferings and unique experiences of another peron. The courage to become someone else and look back at yourself with honesty.

Patience: We lose our tempers because we believe that things should be perfect. We’ve grown so good in some areas (putting humans on the moon etc.), we’re ever less able to deal with things that still insist on going wrong; like traffic, government, other people… We should grow calmer and more forgiving by getting more realistic about how things actually tend to go.

Sacrifice: We’re hardwired to seek our own advantage but also have a miraculous ability, very occasionally, to forego our own satisfaction in the name of someone or something else. We won’t ever manage to raise a family, love someone else or save the planet if we don’t keep up with the art of sacrifice.

Politeness: Politeness has a bad name. We often assume it’s about being ‘fake’ (which is meant to be bad) as opposed to ‘really ourselves’ (which is meant to be good). However, given what we’re really like deep down, we should spare others too much exposure to our deeper selves. We need to learn ‘manners’, which aren’t evil – they are the necessary internal rules of civilisation. Politeness is very linked to tolerance, the capacity to live alongside people whom one will never agree with, but at the same time, can’t avoid.

Humour: Seeing the funny sides of situations and of oneself doesn’t sound very serious, but it is integral to wisdom, because it’s a sign that one is able to put a benevolent finger on the gap between what we want to happen and what life can actually provide; what we dream of being and what we actually are, what we hope other people will be like and what they are actually like. Like anger, humour springs from disappointment, but it’s disappointment optimally channelled, it’s an alternative to going mad. It’s one of the best things we can do with our sadness.

Self-awareness: to know ourselves is to try not to blame others for one’s troubles and moods; to have a sense of what’s going on inside oneself, and what actually belongs to the world.

Forgiveness: Forgiveness means a long memory of all the times when we wouldn’t have got through life without someone cutting us some slack. It’s founded on recognising how awful we have often been.

Hope: The way the world is now is only a pale shadow of what it could one day be. We’re still only at the beginning of history. As you get older, despair becomes far easier, almost reflex. Pessimism doesn’t have to be deep; optimism isn’t necessarily shallow.

Confidence: The greatest projects and schemes die for no grander reasons than that we don’t dare. Confidence isn’t arrogance, it’s based on a constant awareness of how short life and of how little we ultimately lose from risking everything.