Work • Business Skills

How to Better Understand Customers

Every business tries to satisfy its customers. Its products or services may be modest (cheerful socks), very practical (a petrol station with enough pumps) or rather elevated (a life-changing adventure in the Himalayas). But the underlying goal is always defined by a series of guesses as to what we, the consumers, are going to appreciate. Business is, in this sense, about understanding customers. In a functioning market society, profit should be the reward for correctly interpreting the needs and wishes of the audience ahead of the competition.

Yet understanding customers is rather tricky. People don’t go around carrying placards that spell out their longings. It is hard for a company to get to grips with the unarticulated – but crucial – hopes, fears and desires of the people who might buy things from them.

There are many causes of business failure (logistics, internal communication, staff morale, succession, cash flow), but one of the most important and poignant is when businesses go bankrupt because they have failed to understand what it is their potential customers are really looking for; when the demise of the business reflects, first and foremost, a difficulty around interpreting other people’s needs.

So let’s consider certain key psychological insights that effective companies might usefully be alive to when imagining that elusive, crucial figure: the ‘customer’:

1. A lot of what others need is psychological, not material

It can sometimes seem as if what humans need above all else are physical things: they want to move from A to B, they want warmth, sunshine, clothing, more money, houses etc. This is what the bulk of the economy is devoted to generating.

But the flourishing company also has a good grasp on the extent to which our physical needs exist alongside some rather more vague, yet no less real or important, psychological requirements. We have extremely strong longings for impressions of:

– Calm

– Ease

– Reassurance

– Distinction

– Belonging

– Security

– Sexual confidence

– Status

– Novelty

– Purpose…

Struggling companies are often unsure around these appetites. They get the physical product or service right (with enormous effort and intelligence), but then stumble at this hurdle.

However, a good hotel (for example) shouldn’t merely be in the business of offering a comfortable bed. It is also there to advance ideas of calm, belonging or reassurance.

An investment bank shouldn’t just promise higher returns, it needs to understand the deeper psychological wishes that surround money.

And successful car companies know full well that a car isn’t just a padded square box that goes fast: effective cars are bearers of a range of promises about the psychological profiles of those who own them.

2. The ability to teach

Good companies are good teachers. A good teacher has to be hugely conscious of all the obstacles to learning. They have to understand the hidden reservations, doubts and fears which get in the way of someone being receptive to what they have to offer.

Although we never tend to think of commerce under the banner of education, a healthy company, ideally, is an expert teacher, which requires a crucial shift in perspective. One has to identify with the person one is trying to teach: someone who isn’t yet convinced in any way, who doesn’t at all yet know why something matters – something that the company itself has long been very sure about.

Teaching requires a surprising act of imagination, and translation: one has to imagine (or just remember) what it felt like not to know or care.

3. Being kind

Customers don’t typically say out loud that they want a company to be kind. But kindness is, in fact, one of the things we are most sensitive to; and its absence is profoundly disturbing and can be utterly ruinous to modern businesses.

If a company smells too cynical, too much in a hurry to extract profit at the expense of its customers, workers or host planet, this can seem – at first – just good, tough business sense. Actually, it makes the relationship between the company and the customer highly fragile. As in a poor quality relationship, the customer might hang on while there doesn’t seem to be an alternative; but the engagement will be weak and resentful.

There are two big reasons why companies can end up being unkind: arrogance and anxiety.

Arrogance: is a fantasy that you don’t need the other person as much as they need you. It can come from too many years of success. You feel you can get away with whatever you like and they will just have to put up with it. It’s a natural trap for large enterprises because – in truth – they do not usually need any particular customer. Yet to fail at respecting one person is generally a warning sign that one’s in danger of failing to respect many, in other words, that one is close to catastrophe.

Anxiety: in the face of challenges to its very existence, a company may fall prey to the sense that kindness is a luxury it cannot afford. It gets as tough towards the customer as it – perhaps unconsciously – feels the world has been towards it. It starts to get severe, casting aside the need to charm and seduce. It overlooks the first rule of leadership (and parenthood): not to pass on your anxieties to those you are responsible for.

4. Being natural

A lot of failing companies and individuals have forgotten to ask themselves with freshness and originality: what do I actually like? What would really delight me?

So their attempts to please others get stuck in conventional patterns. They follow orthodoxy. They don’t see that they are trying to push on others things that don’t necessarily appeal even to them.

Since at least the 18th century, writers, moralists and artists have been praising the idea of ‘being natural.’ Naturalness really means: confidence around being honest, simple and straightforward about what one really wants.

The natural person doesn’t worry about tradition: about what’s come before. They are more interested in what will be pleasant or exciting or comfortable – even when that might at first seem a bit weird.

To a friend, they might suggest a walk to look carefully at the design of lamp posts; they invite you round to stack the dishwasher or dig a trench in the garden rather than for cocktails. But they don’t do odd things for the sake of being eccentric. The natural person risks being straightforward and simple in the pursuit of genuine satisfaction.

A company might show itself to be less than natural in the stilted language of a brochure or an instruction manual. The description of a resort, a piece of real estate, or airline seat is unlike anything that a real person would ever conceivably say – or want. They fabricate praise, they go in for fake enthusiasm; they fuss and show off.

They want to satisfy customers. But they are too wrapped up in convention, and too cut off from their own native enthusiasms to spot the opportunities.

**

Let’s consider some case studies around some of these basic failures of customer interpretation. Imagine an outdoor sports wear brand. They grew strongly for several years but now things are slowing down. They specialise in clothing for very rugged adventures. A popular advertising campaign from a couple of years ago showed a woman wading thigh deep through a swamp with a knife between her teeth and the distinctive company logo just visible on her high-tech (and very muddy) trousers. They’ve had a policy of only employing – in retail and marketing roles –people who are themselves highly enthusiastic and bold explorers of wild places.

The company has a vision of the good life which it wants other people to share. But it is beginning to encounter the limits of the existing market of die-hard enthusiasts. It is struggling to reach the larger number of people who are less devoted.

The company can be seen as having a deficit around our second point: it has a problem with teaching. It has not yet understood enough about what might be holding back a lot of other people from getting more adventurous and, as a consequence, becoming potential customers for their distinctive products: hats that are good in deserts and gloves useful on an arctic trip.

To help them along, one might put together a short film series of ‘heroic stories’. The build up is that we think we’re going to hear stories of overcoming huge physical challenges – scaling ice-walls and hiking across deserts. But actually, the heroism is about psychology; what we’re hearing are the stories of people who really didn’t think they could face the wilderness, who maybe for a big part of their lives told themselves they were indoor types; whose intimidation had all kinds of origins which they gradually learned to realise and deal with.

Private visits to some of the stores might reveal service staff who were (though good humoured) unintentionally brusque and confused around customers who were inexperienced and didn’t know what they wanted or might need. The unspoken assumption amongst the retail employees was that this was a shop for the already keen and experienced adventurer. They didn’t mean to be intimidating. but they were. This is what led to the loss of a significant number of sales. Slowly, the company should learn to be a better teacher.

Consider another example: an airline set up by a self-made (now) billionaire that is losing market share to hungry rivals. The customers feel that the business is somehow ‘mean’. There is an arrogance around the way seating is allocated and charges levied on bits of extra luggage. One would never mistake the rivals for friends, but this company is starting to seem like a pugnacious enemy – despite the low fares. People will not endlessly tolerate a bullying attitude. It is time for the airline to recover the importance of kindness.

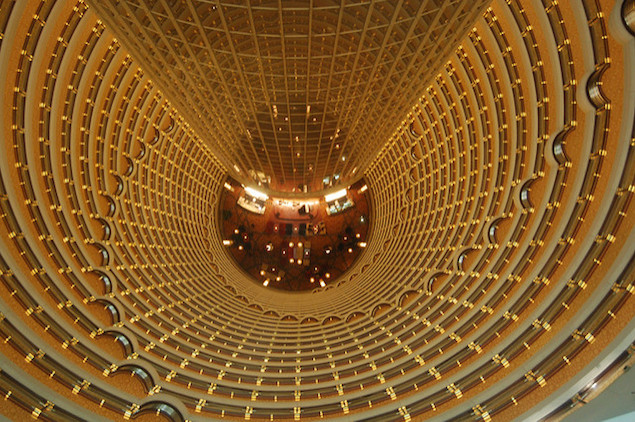

Or think of a luxury hotel chain that is in trouble. It’s been losing customers despite trying to make everything so nice. The hotels are certainly grand: a doorman will promptly open the car door when you arrive; the cocktail glasses will be arranged in perfect symmetry at the bar; someone will polish your shoes; there will be specially designed chandeliers in the lobby; the sheets on your bed will have been made with rigorous precision.

But these well-meaning people have neglected the importance of being natural. In fact, no one particularly enjoys heavy elaborate food on a room service menu; there’s something intimidating about too much gold. The advertising reads as if it was addressing a countess a hundred years ago. The hotel has overlooked what it means to feel really at home.

Traditionally, business consultancies aim at improving efficiency. They work to help companies perform more effectively from a technical or commercial point of view: they cut costs, improve corporate structure and examine tax mechanisms. Sometimes, the more psychologically-minded of them look at staff morale and team learning.

But there’s a big challenge too around a more basic step: making sure that the customer is being correctly understood at more than just the level of price: that products and services are ultimately aligned with the functioning of real human beings, rather than the imagined figures in their creators’ minds. More than the commercial world is sometimes prepared to recognise, good business is – to a critical extent – also about good psychology.