Work • Business Skills

How to Sell

1. The Shame of Selling

A lot of the reasons why our efforts to sell things go wrong is an underlying feeling that ‘selling’ is a bad thing to do. We’ve internalised an image of selling drawn from capitalism’s worst moments, which gives rise to a suspicion that selling somehow injures those to whom we sell.

Arthur Miller’s play Death of a Salesman – first performed in 1949 – is full of pathos and compassion climaxing around the death of Willy Loman, the exhausted, disappointed, middle-aged salesman of the title. The play has been hugely successful, moving audiences from Broadway to China to tears. We feel Willy was an ordinary, good-enough man – who deserved but didn’t get a fair share of happiness and fulfilment. His life as a salesman left him crumpled and defeated. He never accomplished anything; his life was wasted. ‘Salesman’ becomes the name of a person who lived a crummy, inauthentic life.

It’s easy to paint a grim portrait of the salesperson: someone constantly looking out for some way to take advantage of whomever they meet and trying to sell friends and strangers things they can’t afford. A salesperson is someone whose smile can’t be trusted; someone living a life of lies.

But in truth, the moral status of a salesperson isn’t fixed, it all depends on the value of what they are selling. When a doctor urgently recommends surgery to the stomach, we don’t think of this as an act of ‘salesmanship,’ because the procedure (though it might make money for many people along the way) seems plainly and objectively necessary.

The bad image of selling is a consequence of the experience of selling stuff that is unaligned to people’s genuine needs: like too many Krispy Kreme donuts or a Cotoletta Veneziana in a tourist-trap restaurant off the Grand Canal.

We’ve got many vivid pictures of dishonourable selling. But we don’t yet have a correspondingly clear sense of the honourable version. Good selling means uniting an audience with things it really requires to flourish, which means that there is a lot more scope for honest selling than we are perhaps currently ready to acknowledge.

Honourable salesmanship requires a sense of the possibility of honourable capitalism. This doesn’t mean a world in which we’re only trying to sell organic beans and rope sandals. Many companies are already doing good – they’re selling reliable dishwashers and nicely designed garden furniture, good quality skin moisturiser or excellent paper clips. But even these companies often have an unhelpful sense of what they need to tell the world in order to sell their products – and in the process, they lose sight of the good they actually do. Good salesmanship starts with a feeling that there can be such a thing as selling someone something they really require to flourish. It means overcoming the shame of being in sales.

2. Exaggeration

One of the many ways in which salesmanship goes wrong is through a feeling that we need to exaggerate the virtues of a product, service or person – to prove acceptable to a buyer.

The Netherlands Board of Tourism is responsible for marketing the Dutch countryside.

To lure visitors, it has decided to employ images of very neat windmills by pristine canals, with flowers along the banks – and extremely sunny skies.

There are indeed occasional places and a few days of the year when the Netherlands is actually like this. But there are many other aspects of the Dutch countryside that the Board of Tourism stays quiet about: it’s often overcast, there are many places where there’s not a flower to be seen, and there’s always quite a lot of mud. You’ll encounter many a wonky old sluice gate and some rickety pailings shoring up the bank.

To avoid annoying and disappointing their customers, the team at the Netherlands Tourist Board should ideally have consulted a painting in the nation’s main art gallery, the Rijksmuseum, by the 17th-century artist Jacob van Ruisdael. Van Ruisdael loved the Dutch countryside, he spent as much time as he could there, and he was very keen to let everyone know what he liked about it.

But instead of carefully selecting a special (and unrepresentative) spot and waiting for a rare and fleeting moment of bright sunshine, he adopted a very different ‘selling’ strategy.

Selling the Netherlands

His most famous painting is an advert for the qualities he discovered. And they’re much more representative of what Holland is generally like. He loved overcast days. And so he carefully studied the fascinating characteristic movements in the sky: he was entranced by the infinite gradations of grey and how you’ll often see a patch of fluffy white brightness drifting behind a darker, billowing mass of rain cloud. He didn’t deny there was mud or that the river and canal banks are sometimes quite messy. Instead he noticed their special kind of beauty and made a case for it.

The Netherlands Tourist Board, like so many corporations, felt the reality of what it was selling was unacceptable and so had to resort – for the nicest reasons, out of modesty – to lies. But the Dutch countryside is filled with merits: it’s quiet and solemn. It encourages tranquil contemplation. It’s an antidote to stress and forced cheerfulness. These are things we might really need to cope with our overloaded and often plastified lives.

It’s not only corporations that go in for exaggeration. It’s a standard move in all selling. It’s going on when a parent encourages a hesitant teenage child to learn French because, as they put it, it’s the language of love and haute cuisine and because Paris is at the centre of the fashion world. These are attractive notions. But actually learning the language will likely prove a huge disappointment if it is sold in these exaggerated terms, because what the thirteen-year-old is really being sold is Tuesday mornings trying to remember which verbs take être and evenings in their bedroom trying to work out the difference between the past perfect and the past imperfect tenses. Which won’t feel like it has much to do with the little black Chanel dress. The parent’s selling strategy didn’t rest on an untruth. It just deployed an exaggeration. And exaggerations are always likely to lead to trouble.

They could, instead, have tried to identify the real merits of learning a tricky language: that one gets practice in doing things that are difficult (which is an ideal preparation for much of life); that the experience of gradual but real progress is an important one. Or that cultivating a habit of getting exact about fiddly things (like tenses) is maybe just the training they need to balance out their inclination to be vague.

What matters in all acts of truly successful, honest selling is an honourable foregrounding of a thing’s actual virtues – and a confidence that these virtues will in time prove enough.

It’s not so easy to sell this way, because it requires an all-too elusive confidence to sidestep the standard over-sunny stock approaches. But it’s a confidence that should emerge from an understanding of human psychology: we’re all very prepared to accept the less than perfect, if only we can be guided with skill and charm. Exaggeration is a nervous first move in salesmanship. But, as we know yet keep forgetting, things sell best over the long term when the real merits of things are brought out, even if those merits happen to be rather quiet and modest.

3. Idealisation

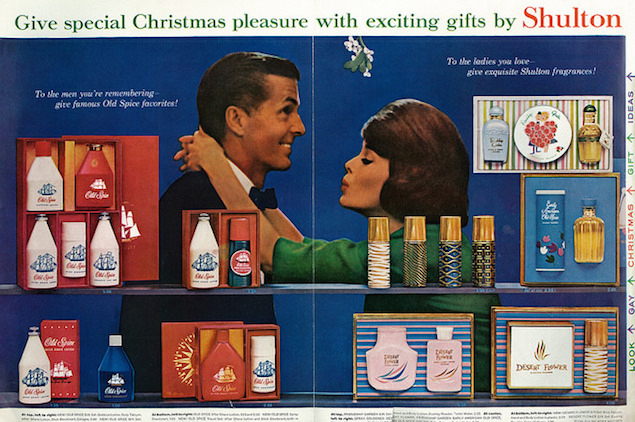

Bad salesmanship believes that seduction requires idealised presentations of life: perfect health, strength, vigour, purposefulness, beauty, family dynamics and love.

Take the way Jaguar has been selling its cars.

He’s in perfect shape, his body is at one with his mind – the ideal instrument of his masculine will; he never gets rebuffed. He doesn’t get assailed by the feeling that his life might be meaningless. He’s not prey to regret, shame, embarrassment or the nagging feeling that he’s a disappointment to his parents.

When confronted with sales pitches like this, we’re likely to recoil. It’s not because we don’t find the images attractive: they’re lovely. It’s because we know in our hearts that our lives (and our bodies) are not much like those on display in the ads.

Unlike the character in the Jaguar, a man of forty might have an unreliable libido (he tries not to think of the fiasco on a business trip to Milan); sex with his partner has become a matter of begging. His stomach is starting to hang over his belt, and the bald patch at the back of his head makes him want to weep.

Companies are missing an opportunity. They might be able to sell more by acknowledging the truth about people’s lives. The solution lies in reminding ourselves of the charm of not idealising.

The appeal of realism is not so well known in commerce; but it’s got a great track record in art. The Italian sculptor, Antonio Canova – who was at the height of his career in the last years of the 18th Century – specialised in making marble figures more perfect than any we might encounter in the flesh.

But consider the paintings of Rembrandt for a quite different approach to physical beauty. One of the people Rembrandt thought most lovely in the world was Hendrickje Stoffels. And because he painted this portrait of her, a lot of other people find her delightful too.

But she’s not conventionally very beautiful. Her neck is quite fleshy, her cheeks are round rather than chiseled, and her mouth is rather small. She’s not very thin either.

She’s interested in her appearance. She wants to look good. She’s arranged her hair carefully. She’s put on earrings. She’s looped a golden chain seductively around her neck. She’s rouged her lips. Yet her face is so appealing not because it is geometrically perfect, but because it seems to convey what’s alluring about her personality: she could get quite sad and thoughtful, she could get confused and embarrassed. She could get angry at times, but she’d likely be quite ready to forgive. She’s warm. She looks as if she could be very understanding.

When we feel we want to look great, it doesn’t mean we want to be perfect. It means we want to be liked and appreciated for what we feel might be most important about our natures. The average fashion brand could profitably imagine what it would be like to employ Rembrandt to devise some advertising for them.

He wouldn’t start with physical issues – what can I do about my thin lips, how can I disguise my wrinkles, I’d like my nose to be less prominent – though he’d get to them later. He’d start by defining attractiveness, rather than perfect beauty. And he’d build an initial campaign round the idea; what do the very beautiful really want: do they want to be liked? He’d be driving a psychological wedge between two ideas we’ve confused: physical beauty and attractiveness. Physical beauty is a guess about what’s genuinely appealing. But it can’t be quite right because Hendricjke is more attractive than the average supermodel, though by the standards of physical beauty Hendrickje is far less perfect. He’s advertising a fundamental truth.

Let’s return to the landscape. Up until the early years of the 19th century, the English landscape was painted in idealised terms. Artists would go to Italy and look at sunsets over the bay of Naples or climb hills and gaze down at sun-kissed plains; they delighted in serene skies and feathery trees. And when they returned to Derbyshire or Surrey they’d paint these places in the same Italianate terms.

Richard Wilson, Syon House, c. 1761

John Constable, on the other hand, got interested in identifying the real charms of the English landscape as he actually saw them.

A cloudy sky could be lovely, the sandy colour of a gravel pit is actually very nice; the dumpy little hills are sweet. Instead of pretending the place lived up to an impossible ideal, he became very attentive to its odder but still very real attractions.

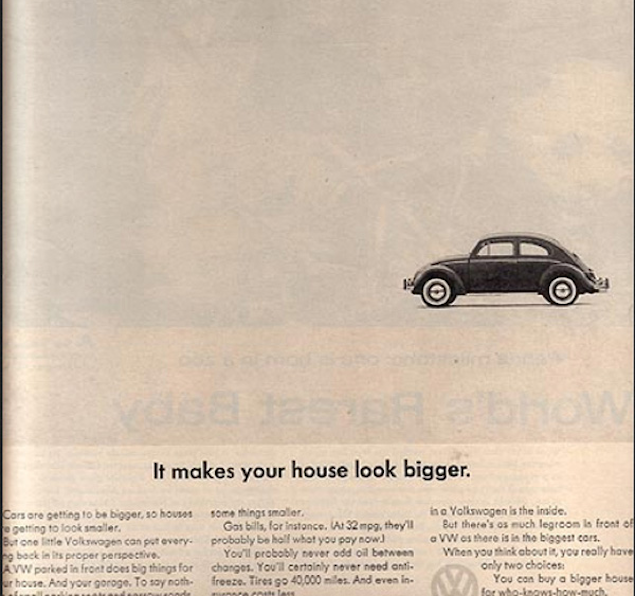

Like Rembrandt or Constable, a series of adverts used by VW in the 1970s explore the appeal of the ordinary and the allure of candour.

Like a charming, mature person, the ads are able to admit that the product isn’t ideal. VW have confidence in experience, which teaches us that no one’s life is remotely ideal. You can honestly admit some problems and still be pretty good overall. The real virtues are still there, despite the drawbacks. In reality, we all accept this all the time. The job is far from perfect, but it’s still a decent place to work. The children’s school is far from perfect, but it does some things very well. And anyone seeking perfection in a partner is guaranteed to be miserable. But we get nervous around such obvious ideas when it comes to selling. The approach VW uses here is charming because it addresses us as the adults we really are.

Incidentally, VW have themselves more recently become infatuated with Canova – unfortunately for the appeal of their advertising.

They’ve become worried about the ordinary. They’ve been corrupted by the Romantic idea that to be good something has to be unusual. (Which is – ultimately – a tragic idea because it implies that we’re almost all bound to be unhappy, since by definition almost everyone’s life will be ordinary).

Jaguar are making more upmarket cars; so it’s not really their vehicles they might be winningly modest about. It’s the drivers. Rather than fabricate an ideal, polished customer, they could be sweetly candid about the driver’s likely shortcomings. We’d suggest a campaign built around slogans of this kind:

Your marriage is a bit of a disappointment, fortunately your car doesn’t have to be.

Your performance is unreliable; Jaguar’s isn’t.

It’s lean, even if you’re not.

It will make you look more impressive than you actually are.

Driving a Jaguar is where life makes sense. Life is where it doesn’t.

The campaign is making friends with the potential customer by – like a real friend – liking them, while being perfectly aware of their imperfections. A friend doesn’t like you because they’ve failed to notice the ways you are considerably less than ideal. They appreciate your merits and and sympathise with your tribulations and weaknesses.

The typical modern advert is Romantic. That is it adopts one of the key ideas of the Romantic Movement which dominated European and US culture in the 19th century and whose effects are still very much with us. Specifically, they buy into the conviction that only the special can be good. They associate the notion of being ordinary with failure and dreariness.

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron, by Richard Westall

By contrast, the Classical vision of culture is interested in, and enthusiastic about, the good ordinary. The classical outlook is very keen that the average should be nice. It assumes that what is normal can also be great. The task isn’t to make sure that one focuses on what no one else has. Rather the real business of culture – and of commerce – is to make what is common also rather good. From the classical point of view, to brand a product as ‘exclusive’ is to admit defeat.

Idealisation is the enemy of the good ordinary. It is a problem that afflicts us not only in the marketplace, but in personal relationships too. So often in relationships we dream of how wonderful life could be, if only… And it leads us to under-rate the value of the more commonplace, but genuinely good things that are within our grasp. There’s a kind of salesmanship that doesn’t only get better at tapping into our needs; but which – along the way – helps us recognise, and properly esteem, the worth of the life we are mainly required to live: an ordinary one.

4. Underconfidence

Japanese aesthetics manages to get excited about things which are, on first hearing about them, desperately unprepossessing. They talk enthusiastically about moss, drafts and – especially – broken pots.

The concept of kintsukuroi – which means more beautiful because it has been broken – helps direct attention to an easily missed appeal. The Japanese enthusiasts are not pretending. The repaired pot really is beautiful. It’s just that if you come to it with unhelpful preconceptions you’ll dismiss it out of hand – and never get round to noticing its charm.

Concepts like ‘kintsukuroi’ are in the selling business. They’re not initially charging money for a product or a service, so it doesn’t look like selling. But Japanese aesthetics are selling in the more fundamental sense of persuading someone to appreciate and want something. And further down the line people will be willing to pay to have this sort of thing. So there’s a market in Japan for nicely repaired bowls – a branch of commerce that is not yet much evolved in Sydney or Manchester. And in Japan, the value of a property will be augmented by the fact that the little tea house in the tiny garden has especially good drafts that cause the paper scrolls to flutter in a way people (in suburban Yokohama) have come to find enchanting.

The point isn’t that we should get interested in building up businesses supplying pre-smashed crockery or installing drafts in people’s homes. Rather, these case studies teach us a useful kind of confidence. Things that might easily be thought unworthy of appreciation can – if described in the right way – emerge as attractive.

People who have learned how to sell broken pots and imperfect insulation might have something to teach us about marketing things we currently regard as ‘low’ and unworthy of much attention: air conditioning units, filing cabinets or cereal packets (which we’ll be looking at in more detail in section 5).

The general thought, which we meet here repeatedly, is that good people panic around selling. They head too quickly to what they assume is the only thing the target audience will tolerate. If you speak about less familiar merits or demerits, you fear people won’t come on board.

This doesn’t just apply to commercial situations. You might be going to get married and feel that you have to have a wedding with an elaborate dinner with seven courses when in truth you feel it would be lovely just to have cheese sandwiches and mini Twix bars – the wedding equivalent of a smashed pot. But you instantly dismiss this from your mind as ‘impossible’. People won’t get it. Your partner will object, the guests will be disappointed. What you are held up by is not something actually wrong with your idea. In fact, it could be an extremely happy occasion. And in reality – you feel sure – most people hardly notice what they’re eating on such occasions. You’ve got a good case, but you don’t make it because it feels too weird. We’re very scared of rejection. We’ve created a fragile social environment in which unless you boost, it will be rejected: unless you emphasise how elaborate the occasion will be you’ll look cheap or mean or antisocial. The people, actually very few of them, who do feel intently that weddings should be highly complicated have projected their attitude strongly, with desperate effectiveness. They’ve made it look as if this is the only plausible option. When it really isn’t.

All of us probably love a grandmother and a child – people who, almost inevitably, by the standards of the world are nothing terribly special, maybe a bit difficult or awkward in a hundred ways. We know how to do this: love imperfection with boundless enthusiasm, because we do it all the time. Inbuilt into life is a rich capacity to love what is imperfect, starting with our loved ones. But we lose confidence in this actually widespread capacity. We panic and forget that others actually can readily activate this side of themselves – and that this is in fact the task of selling.

So we miss the opportunities for ‘selling’ (speaking of the virtues of) things that many people might like – a sandwich at a wedding, a repaired pot, a beaten-up table, if only it were confidently offered.

5. Shouting

At breakfast, you are confronted by a smallish portable billboard, which also doubles as a container for cereal.

© Kellogg’s UK and Ireland

There’s quite a lot it wants to communicate – with the goal of getting us to drop a packet into the trolley next time we’re at the supermarket.

– Their breakfast offering is going to charge into your life like a train rocketing towards you across the wheat fields of the Midwest.

– The product is bursting with energy.

– It’s filled with sunlight and big skies and made from perfect ears of corn. And you mustn’t forget its nutritional advantages either.

But the box is worried. It’s anxious that you might not be paying proper attention. It imagines that the ambient noise at this moment is quite high – maybe you’re listening to news of a political scandal, perhaps you’re glancing at the weather forecast; maybe you’re coordinating the day with your partner or trying to think where your child’s Peppa Pig wellington boots could be hiding.

With all this competition around a Weetabix box wants to cut through and make you listen to what it has to say. And to do this it shouts. Weetabix uses the strongest colour contrasts, they ramp up the intensity: the sunrise is explosive; the sky is intensely blue; the wheat is perfectly golden; the lettering is huge, they make point blank assertions of the virtues of their product. Every bit of the surface has been made use of to keep the volume as high as possible. If they could, they might fit flashing lights and a claxon.

But there are other ways in which messages get across and win our attention in a crowded world. Shouting isn’t the only option: it’s just a very familiar one at the moment.

An alternative to using a loud voice was explored by the English artist Ben Nicholson (1894–1982). He specialised in a very low-key, semi-abstract approach to scenes of everyday life. He wanted to dim the volume of what he was saying so much that others would have to turn down the ambient noise.

Packaging for a breakfast-time product

He muted the colours (he was very fond of light grey); he used delicate harmony and clear, simple shapes to impress us. He realised that – for all that’s going on around us – we’re actually very responsive to certain dim signals. Something can stand out from the crowd precisely because it is quiet. His works are very calm and self-possessed. It’s a quality we recognise and like in people. It’s the person who doesn’t have to raise their voice to be listened to, the speaker who can hold the attention of a room even though they speak without assertion and pause between sentences. They’re not mumbling or bashful. There’s a real, convincing, authority behind their words.

Ben Nicholson had the confidence to know we could be charmed by a bowl of fruit on a modest table. We could warm to subdued tones. We could like the simple outlines and rapid hinting of shapes. Many people happily hang images like this on their walls at home: the average Ben Nicholson costs many millions now. Yet the designers working for Weetabix forget this side of us when they’re planning the look of their boxes.

Shouting gets attention, but it doesn’t persuade. It doesn’t change hearts and minds. We’re really seeking not just to get someone to notice us, but to understand and appreciate the point we’re making. We ideally want them to listen carefully. And for getting that result, Ben Nicholson offers a vital lesson.

6. Cheeriness

Across history, the articulation of melancholy attitudes has won immense audiences – Keats, Baudelaire, Amy Winehouse and thousands of singers enchant us with their appreciation of the sorrows of existence. We’re deeply attracted to their ability to speak of the more sombre aspects of life: we love and get left; our hopes are routinely frustrated; people we need get ill, they die; so many lovely things are fleeting. Summer passes, a friend moves away, one’s hair thins.

Melancholy is a species of sadness that arises when we are open to the fact that life is inherently difficult and that suffering and disappointment are core parts of universal experience. It’s not a disorder that needs to be cured. The good life is not one immune to sadness, but one in which suffering contributes to our development. Sometimes you feel sad and you can’t quite put your finger on why. It’s not one acute sorrow that’s eating you. You feel in a way the whole of life calls for tears.

Melancholy sells

And yet advertising almost always forgets this. It is relentlessly cheerful. There has hardly ever been a melancholy advert.

We’re amazingly cheerful over here

Selling is mesmerised by the idea that when we feel a bit sad – when we’re touched by melancholy – what we need is to be at once very vigorously cheered up. It’s not a silly idea and sometimes it works. But by only using this approach the salesperson misses the opportunity to reach us in other ways.

The central move of melancholy art – in songs and poetry especially – is to comfort and help us by not trying to cheer us up. It’s a move we understand intuitively in the darker times of our own emotional lives. The sympathetic friend doesn’t pretend that all is well. They don’t say, it doesn’t matter that your parent has died, that you’ve been retrenched from work, that the novel you’ve been working on for seven years has been rejected for the 22nd time. They do us the honour of acknowledging our sadness and recognising that it is called for. In the darkness, they stretch out a hand.

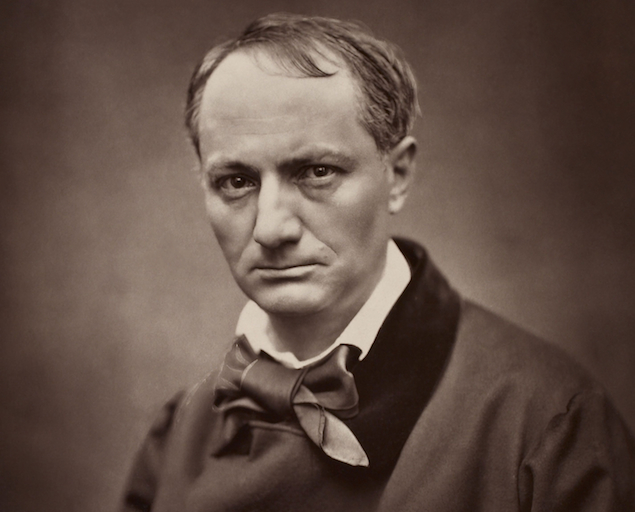

The idea of not trying to cheer people up – but of offering another kind of kindness – was at the heart of the work of the French poet Charles Baudelaire (1821 – 1867).

Baudelaire was extremely well acquainted with grief. He had a miserable relationship with his socially prominent stepfather; he was addicted to gambling, he was infected with syphilis at an early age, he squandered his inheritance. He found the process of writing agonisingly difficult.

In To the reader, he addresses us directly:

— Hypocrite lecteur, — mon semblable, — mon frère!

Which is to say, in effect: you my reader are a hypocrite, you are like me, you are my brother!

In calling us hypocrites, he’s not being insulting. He’s acknowledging that we often pretend – specifically, we pretend to be happier than we really are. He won’t be telling us that everything is going to be fine but he offers us his companionship, because he knows our troubles (and more) from the inside.

Advertisers think they have to tell something cheerful – rather than, as is the truth, confirm the legitimacy of their true, sorrowful feelings. They’re forgetting to address us as mature people: individuals who can, with a little help, accept complexity and compromise.

The idea isn’t that advertising – or selling more broadly – should undertake a volte face and always be melancholy. What we’re suggesting is that it could very usefully extend its emotional range. It could sometimes meet us in other moods.

This has big implications, because there are needs we’re more alive to when we feel a bit sad. We don’t stop being consumers when we’re down; but we have different priorities. One could project a financial services company that routinely demonstrated that it was in touch with our sorrows; or a gaming company that could pick up our interest in our melancholy times. There is a market for more modest, more down-beat products.

Think of a firm wanting to hire the best new recruits. The natural temptation is to be very cheery about working for the firm – everything is sunny, the work is fascinating, the team is shoulder-to-shoulder. But many of the most talented, resourceful and loyal potential staff will be complicated individuals. They’re less robotic, more realistic about themselves. To draw them to your firm, an admission of life’s sorrows (including the sorrows of work: ‘sometimes its disappointing and there are days when we all wonder if it’s really all worth it’) could be a crucial advantage.

7. Inauthenticity

Salesmanship goes wrong when the seller comes across as inauthentic. They seem not quite a real person: too smooth, too slick or over-friendly (but not actually a friend). Their efforts to appeal – and to win the trust of the customer – backfire.

The product itself might actually be pretty good in many ways. It’s the effort to sell it that’s going wrong.

Inauthenticity stems from mistaken assumptions about what other people want and what they are like. The seller moulds themselves to what they erroneously imagine the customer wants them to be. They adopt an attitude they don’t personally like in the hope of pleasing the client. It’s a wrong theory of what you would need to do to win other people over. And it tends not to work terribly well, because we’re all amazingly astute detectors of fake emotions.

– The management of a resort hotel might think: we should pretend to be servile to the clients – presumably that’s what they want even though we don’t like it when people do that to us. With the result that a family never goes back to a particular hotel on an island they love. They complain to their friends that the staff seemed plastic and a bit creepy.

– An aspiring novelist feels: I’d best lace the story with references to luxury products and Bond-type violence, even though I personally find that a turn off, because that’s what sells isn’t it? The publishers turns down an otherwise promising manuscript. In the commissioning meeting, the book is rejected because it was felt to lack conviction.

– A stockbroker wants to build up the relationship with a significant client and takes them out to lunch, thinking: I’ll chummy them along with talk (that bores me to tears) of golf courses and school fees. The result is the broker appears false and untrustworthy, and the firm loses the account, despite the fact that the results last year were pretty good.

– A high-flying professor of economics is co-opted by a major political party to help sell their economic policies to the electorate. They clown around in an interview on Sunrise and come across as condescending. Some important ideas about the nation’s finances lose credibility and get put on the back-burner.

– A woman fears that her partner won’t stay with her unless she pretends to be more outdoorsy than she really is. She psyches herself up to seem enthusiastic about a camping trip. Eventually her misery become obvious and the relationship falls apart. Or, worse, she hates it but puts on a brave face. She ends up dreading every holiday for the next ten years and it ends in a bruising divorce.

– A company wants to improve the calibre of recruits it takes on, in view of a big expansion into new markets. They’re offering a competitive salary but feel they need to woo the very best candidates with an airbrushed vision of the firm’s character: it’s dynamic, thrilling, everyone’s great friends. Though they themselves know it’s not perfect but accept it for what it is: intermittently interesting, occasionally frustrating, riddled with normal workplace tensions – that is: much like other places. The interviewees they are most impressed by get the sense there’s something not quite right and turn down the job offers.

The person, service, product or employer on offer may have some real merits. But the selling fails because it’s not authentic.

There’s a very natural worry that leads one to this: in my heart of hearts I think that what I’ve got to offer is pretty good, if I were them I’d take it. But I fear that if I tell it like it is, they’ll reject it and me.

Inauthenticity is rooted in lack of confidence: specifically a lack of confidence in your own responses and desires and intuitions and an assumption that other people are very different from you.

Our best source for understanding what people are going to like or cope with is, in fact, ourselves. How you like to be treated, what you enjoy eating or reading, what you accept as OK gives very good guidance to how other people are likely to respond. (Of course it’s not a 100% guarantee that everyone will share your response. But that’s never what’s needed. No company on earth can get – or realistically seek – every customer in a competitive market.) Weirdly, though, we tend not to take this information seriously. We don’t recognise its importance. We don’t let it govern our salesmanship.

In authentic selling the seller trusts their own personal responses. They build on the idea that the Other is likely to be quite a lot like them. They come across as charming. You feel that someone is charming, not just because they’re being polite but for a bigger reason. You feel they’re intuitively in touch with your needs. For instance, they might quickly pick up on when you feel slightly awkward and deftly move to reassure you – even if it’s only with a sympathetic smile. What they’re doing in fact is using their own experience of feeling ill at ease to tune into what’s going on for you. They’re doing you the courtesy of thinking that since they’d feel awkward in your shoes, you’re probably feeling awkward too (though you’ve not explicitly let on). An air steward becomes charmless if (for example) they ignore their own experience of being occasionally baffled by technology and give you the impression they think you’re a bit of an idiot because you’re having trouble operating the entertainment system. They are assuming that they are not like you and opening up a gap which charm works to close.

Charm is a common factor in lots of good selling situations: good writing, a good lunch companion, good public speaking or producing good copy.

The 16th-century French philosopher Michel de Montaigne has a couple of things to teach us about charm. He took the classically leaden and chilly philosophical essay and delighted his contemporaries (and subsequent readers down the centuries) by transforming it into something engaging. He’s got serious things to say but he says them in a charming way.

He acknowledges the fears of the audience

It’s natural to get a bit anxious around intellectual matters; one is going to lose the thread, get bored or feel humiliated. Sometimes Montaigne is upfront about this. He’ll say, this is getting too complicated or this is starting to be tedious. But he acknowledges it in other ways too. He keep his chapters short. He uses lots of concrete examples. He adds in jokes. He mocks people who are intellectually arrogant. All of these signal that he’s attuned to the secret worries we might have. He didn’t work this out by consulting a focus group. He knows we have these fears because he’s noticed them in himself. He’s authentic – and charming – because he’s working from the belief that we’re pretty much like him and so he can trust his own feelings in our company.

He reveals things about himself that go beyond the so-called polite

Montaigne is an unusual author because he’s ready to let down his guard and tell us things about himself that people tend to feel a bit ashamed of and to keep quiet about for fear of losing the good opinion of others. He recounts his bouts of impotence. He admits he farts quite a lot and that he has trouble with his bowel movements. He’s not only parading his vulnerabilities. He’s doing it because he knows it’s a way to get us to feel relaxed in his company. He’s demonstrating he’s like us – even though unlike us he knows a lot about Greek literature and the secret goings on of the diplomatic world. We’ll go with him on his travels through the world of ideas because he’s won our confidence with his candour.

Montaigne is showing us that the way to get good results is to acknowledge fears and frailties. In another context, it’s the way a great general gets the best out of his troops because he’s always showing that he knows what it feels like to be on the front line. It’s the senior manager who can good-humouredly fix a paper jam in the copying machine, and the teacher who is powerfully alive to what it’s like to be nine.

Charm is a graceful acknowledgement of our reality. The failure to make this acknowledgement – the shortfall in charm – explains what can go wrong in:

The half-empty stiff, posh restaurant. The management hasn’t clearly enough identified what they themselves enjoy about elegance. So they’ve ended up creating a slightly pompous, frosty atmosphere.

An uninteresting novel. The writer has read a lot of the big famous works. When Dickens takes a character into a house, he always gives an elaborate description. He doesn’t just say, ‘They went to Jim’s place.’ He says something like: ‘James O’Donnell (after his late and occasionally lamented mother) Merriweather – Jim to his confreres – was the fortunate denizen of a delicious set of rooms perched in the higher regions of one of the more recently constructed communal mansions of that portion of our capital officially designated as Battersea. They climbed the several flights of carpeted stairs and arrested themselves before a portal of average dimensions but distinguished by a curious knocker emblazoned with the word ‘SALVE’. With a self-conscious flourish Jim extracted from a pocket a simple key …’ Forgetting what they themselves are excited by as a reader, their own novel gets more elaborate, more dull. They forget to omit the uninteresting bit that they’re inclined to skip when reading.

Boring social evenings. The conversation never quite takes off and people are cagey with each other. The hosts haven’t been able to home in on what they themselves are actually like – what they actually liked about the best parties they’ve been to. Probably they’ve picked up on incidentals. They went to a delightful dinner where (as it happened) they were serving Japanese food. When entertaining, they focus a lot of attention on the sushi. But though the fish was great, that wasn’t actually what made the evening they recall so special. It was actually the way the hostess introduced people to one another, the way the host unobtrusively steered the conversation into very interesting waters – these were the active ingredients. And our couple enjoyed them, but without quite realising it. And in giving their own parties, they don’t focus on the things that really make an evening work.

It’s hard for us to hold on to our common humanity. And it means that our efforts to sell (ideas, social companionship, tables in a restaurant) to other people get derailed.

There’s a typical sales strategy that tries to avoid acknowledgement of potential problems. It’s an instinctive move, built on an an underlying theory: if you mention the problem, it gets worse. But in selling, it’s a liability. Because the problem is going to emerge at some point. You’ll lose future sales, have disgruntled customers on your hands and discover there’s a popular Facebook page for people who feel they’ve been let down by you and want the world to know all about it.

Charm has a very distinctive attitude to problems. The charming person sees a problem as a potential bond – a shared difficulty. We pick up on it socially. They’re in the car with you and you struggle to get into a parking space (though it’s not really that small): they don’t look down on you. In a minute they’re telling you how they’re nervous of roundabouts and steep hills. The little indignities of driving become a private joke between you. Charm has a good attitude to mentioning problems, founded on the charming person’s readiness to see problems as a normal and interesting part of life. They know everything has its downsides. A problem isn’t fatal. So there’s more confidence in being upfront about defects.

Charm sells not because it is (as its detractors suggest) sleek and ingratiating. No one finds that charming. But because it grows out of self-knowledge and confidence in shared humanity.

8. Bad Teaching

Selling is often an attempt to teach the merits of a product or service (or of oneself) to another. So selling gets into trouble – that is, it gets less effective – when the seller is a bad teacher.

What actually makes someone a poor teacher? No one is deliberately setting out to fail to teach. But bad teaching is not inevitable. There’s a central error the ineffective teachers make.

The bad teacher has forgotten the fears of the audience

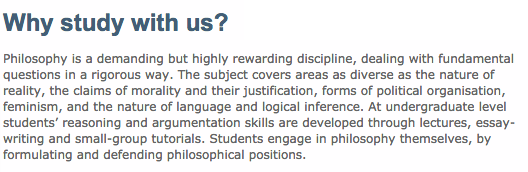

We can take a look at this happening in higher education. Philosophy departments typically want to get more students to attend courses. They want to grow their numbers. So they advertise.

Here’s an advertisement for philosophy from Birkbeck College, which offers courses in central London in the evenings for adult learners – anyone can enrol.

The advert is written by people who know a lot about philosophy. They’re adept at constructing sophisticated theories. But they’re less good at handling some widespread fears around intellectual life. It could be boring. The class could be filled with awkward people. It could all be baffling. The promotional page doesn’t tune into the worries. It inadvertently enhances them. We’re now queasy at the thought of trying to identify ‘the nature of reality’ or daunted by the prospect of ‘dealing with fundamental questions in a rigorous way’ (one may end up dealing with them in a sloppy way and get humiliated). The bad teacher is impatient with the fears we have. They blame us for having them. Which does nothing to bring people in or help anyone to learn.

There are lots of areas which fail to appreciate widespread fears and reluctance in the modern economy:

Flossing products tend to stress the positives: look at how lovely your teeth will be when you’ve been flossing regularly for a long time. You could be like her.

They’ve neglected a set of anxieties that in fact get in the way of more people buying their product and getting on with the job. One feels: I’ll get bored, it’s depressing looking at my very imperfect teeth in the bathroom mirror; it’s too fiddly. We don’t take pride in these negative feelings, but we have them. The advert aggravates them by showing us someone who seems to be great because they are entirely free of our troubles.

They could develop some adverts using people with these fears: a spotty teenager looking blearily into the mirror and swearing every time the floss slips and cursing the red marks on their thumb where the thread has been pulled too tight.

Or there’s the macho sportswear manufacturer who has forgotten the fears people have around sport.

They love rugged athleticism, they’re keen on pushing themselves; they enjoy the banter of the locker room. But most people aren’t like this. Mostly we’re pretty anxious around sport. We don’t win. We’re not very fit and we’re intimidated by those who excel. So the advert ends up sending us the message that the product (and the whole area of life it is related to) isn’t for us.

Bad teaching is a commercial problem for the seller: they aren’t reaching a segment of their potential market. But it’s also a loss for us – the consumers whose fears are ignored and cast as embarrassing. Because what these companies are selling isn’t just floss or running shoes. It’s healthy gums and confident enjoyment of exercise. And these are things we need in our lives. They’re making it harder for us to live well because they increase our anxieties (or at least don’t calm them down) around things that would actually be good for us.

The good teacher is onto the fears and resistance of the audience

As we’ve seen, any product or service has around it fears that are holding back growth.

Fears could include the worry that something is:

– too intellectual: I can’t purchase that book, see myself reading that newspaper

– too rugged: I can’t buy a tent

– too technical: I can’t have that coffee machine in my life

– too feminist: I can’t watch this comedy show

– too sexist: I can’t buy this car

– too Brazilian: I can’t join that dancing class, work for that firm

– too American: I can’t go to that restaurant chain

Good teachers (and sellers) don’t say: you shouldn’t have this fear. They don’t send out signals that only inadequate people have worries like these. They don’t stay quiet about them. Instead, they take them by the horns. They acknowledge where people are starting from and work from there. They don’t feel that acknowledging a fear is the same as endorsing it. They believe that acknowledging a fear is a key moment in a process of overcoming it.

Sir Humphry Davy (1778 – 1829) was one of the great scientists of the 19th century.

Admired by his scientific peers for proving that oxymuriatic acid does not contain oxygen

He was a very serious man. He was a pioneer of electrolysis. He helped discover the elements barium and boron.

But Davy was also very ambitious for the contribution science could make to our lives (he invented a special lamp for miners to use underground) and he wanted to see a society where scientific understanding was widespread, not reserved for a few specialists.

He became very popular for the talks he gave around the UK. He was brilliant at drawing people in. In his public lectures lectures, he always had lots of explosions, smells and clouds of steam – he loved making jokes.

He realised that a key fear of the audience is: it will be too serious. He didn’t feel that science is so important and serious, it is above fun. He realised that it has to be fun if a lot of people are going to engage with it. He didn’t look down on people because they were nervous around complicated things. He realised he could make some moves that would disarm these anxieties.

Jamie Oliver realises that for a lot of men there’s a fear around cooking certain things: it will be too feminine. There’s a powerful subterranean worry that you can’t be a proper man and cook asparagus and mint risotto.

But Oliver never gives the impression that it’s stupid or low to have this anxiety. He makes a great play of being blokey and doing some things which social tradition has made feel unavailable to key groups of people. He’s turned addressing this fear into a career.

What distinguishes these great teachers is the way they view the fears of the audience. They don’t get angry or annoyed. They don’t blame people. They are unthreatened by the fact that someone has some worries. Because they don’t see a fear as the end of the story. They know that fears – if treated nicely – can be disarmed.

9. Badgering

Selling goes wrong when it pesters people. And unfortunately, a lot of selling and advertising is annoying. It turns up at awkward times and in places where it’s not wanted.

It spoils your street.

You get out of the shower to answer the doorbell – it’s people selling an animal charity. Or, your computer is bunged up with pop-ups. Every day you encounter thousands of promotions for products you don’t need and will never buy.

The problem isn’t with the products. The burgers could be fine, the charity is deserving, the agents might work round the clock in the interests of their clients. The things you don’t need might be exactly what another person requires. The problem isn’t selling as such. It’s trying to sell to the wrong person at the wrong time. Badgering has two characteristics:

Randomness: they’re assaulting the whole world because they’re not sure how to reach their real audience

Untimeliness: they’ve not managed to get you at the point when you’re receptive

There’s a version of badgering in relationships: nagging. The aim might be really very reasonable – this person should take out the rubbish or clean their room. But the approach isn’t helpful: repetition of the demand at inopportune moments and lack of insight into how to motivate this person to do what you want. Nagging is sadly liable to make compliance less likely.

In love, badgering gives us the stalker. It’s the person who knows they are keen on someone but has no view of why the other should be interested in them. They have no seductive resources and simply impose themselves in a deeply unpleasant manner.

Badgering is commercially counterproductive. It’s a poor selling strategy because the annoying methods turn many potential customers off the products. It might get you a little bit of acquiescence, but you lose goodwill.

Why sellers end up badgering

There are a few reasons companies end up badgering the public:

The age of the internet

By reducing the cost of getting at people, technology encourages randomness: you can bother tons of people, even if you only end up getting one or two.

Lack of empathy with the customer

Badgering grows from an unflattering – and mistaken – picture of the customer. It supposes

– the customer can only respond to loud noises

– can be won over by sheer repetition

– will readily respond to vulgar signals…

This isn’t how the sellers themselves feel and behave. They don’t like being pestered. But they don’t think of their audience as being basically quite like them in this respect. They lose touch with their own experience when devising their selling strategy.

Minimal customer information

It’s an approach that suggests the seller doesn’t know the customer’s needs and aren’t very interested in finding out more: if you knew anything about me, you wouldn’t be trying to reach me this way. Maybe I could be persuaded – just not the way you’re going about it.

Low self-esteem around the product

Giving the impression that you are trying to force a desire (and a product) on the customer – suggests you don’t really feel that you have anything genuine to offer. It suggests that the seller doesn’t quite believe that the product would, on its own merits, be wanted.

Selling in the Utopia: approaching the right person at the right time

Currently a lot of people have to be bothered so that a few people can be pleased. Or you are targeting the right person, but at the wrong moment. How do we get from where we are to the utopia, where we’re addressing the right person at the right time?

Growing out of Nagging

Badgering people, and nagging, are natural strategies for gaining attention. We used them as babies, when we had no other options. A baby’s wail makes the carer respond, even if they don’t want to – just to get some peace and quiet. The six-year-old has no capacity to rationally persuade his parents to buy him a goldfish but will instinctively assume that asking a million times will work (and occasionally it does). This is where we all have come from. We carry a lot of residue. And when we’re under pressure when stressed, we return to these early instincts.

The path of growth towards adulthood involves getting better at three things:

Greater awareness of who you are talking to and their needs. The badgering child doesn’t really understand why the parent won’t agree. The child thinks: maybe they’ve forgotten (in the last three minutes) so I’ll ask again. Good growth here means getting more aware of what the parent’s reservations might actually be. The art of persuasion evolves via working out how to address the worries. So at fourteen, the child might be drawing up a little document called: why I should be allowed to go on the school trip to Berlin.

Worry one: it would be too expensive. But you wouldn’t have to feed me for three weeks.

Worry two: I didn’t get a good grade in German last term. But that’s because I don’t see the point of learning a language I don’t need to use. Going to Berlin would change that. It would motivate me.

Worry three: You think I’ll get homesick. Remember I was fine when I stayed with granny for a week when you went to Atlanta.

Getting more sensitive to the context. The child might learn that their aunt’s rather luxurious flat is not a good place to ask their parents for anything, because that place tends to make them feel anxious about money.

Timeliness. They know that their mother is very likely to listen carefully at 3.00pm on Sunday, and not at all at 7.45 am on Monday. Or that the drive home from school is the ideal time to make a big request.

The same three points apply equally in commercial selling:

Finding out more about the potential customer

The more I can allow myself to find out about the customer, the less I’m inclined to badger or nag. This means getting a more accurate, insightful picture of their concerns and needs.

The ideal of commerce is that it is delivering on the needs a person truly has – even on ones they don’t at first fully recognise they have. It might be actually a great contribution to someone’s life to take a trip to the Colorado desert; or make a career shift or buy a ten-seater dining table (though at yet such needs haven’t crystallised in their mind). A friend might see these things. The friend could recognise the need on the basis of understanding the person’s life. That doesn’t mean tracking that they’ve just purchased some toothpaste or that they’ve watched six episodes of House of Cards on Netflix last week. Rather, the friend can see what’s happening in this individual’s life: how they are getting sucked into preoccupation with status (hence the merits of the desert – where status doesn’t count); or there’s a level of cynicism about work building up, that’s probably connected to the industry they are working in; or they could do with improving relations with their extended family – but on their own terms. Getting them a big table regularly – like their parents used to do – would be a great help.

To get to this level of insight would require building up a huge amount of trust between the seller and the potential customer. At the moment, selling is fragmented. You buy different things from different people. You might trust them in one area (they are excellent at supplying children’s T-shirts, or a reliable place to book flights) but it doesn’t extend to offering these suppliers a portrait of you as a person. Yet in principle, there’s a huge benefit for the customer. The supplier acts as their friend, in their best interests, grounded in real understanding of their best interests and needs.

Sensitivity to the context. A hamburger doesn’t go well with a ploughed field. Everyone’s slightly aware that a hamburger might not be the most natural thing in the world. And you might not want to advertise a luxury handbag anywhere near a bank. Context foregrounds certain aspects of your mind.

Timeliness. This means understanding when a person is in the right mood to be receptive to the sales pitch. It’s not exploitation. It’s realising that there are times when we’re more alive to important truths and grasping that at other times we may be very annoyed if we’re addressed on certain matters. (Everyone recognises this in their own life).

It might genuinely be wise for an individual to sign up for an exercise program or have a body scan. But quite probably, they are very resistant to thinking about these things. There might just be a few times in a year when they are able to look squarely at this genuine need. Getting them at such a point (with a sincere and decent offer) means engaging with their own better, but often hidden, nature. You are doing them a huge service if you can discover a good moment at which to raise a tricky topic.

These moves all build on the same underlying point: a higher quality of relationship between the seller and the potential buyer than is currently familiar. Badgering is the polar opposite. Trust arises when the seller is seeking to make a profit only from making a valuable contribution to the customer’s life. We could imagine a commercial utopia in which this was standard practice.

10. Fear of Success

Selling can go wrong for many people because they are afraid of success. To sell would be to succeed and this makes them anxious. So they end up avoiding selling or bungling the opportunities. It’s a problem that can sound unlikely. Because we sometimes assume that everyone is keen to succeed. Being afraid of succeeding sounds strange. But it happens quite a lot:

You’ve been asked to make a presentation to a large and important audience. You feel terrified. You can’t sleep and try to think of ways of getting out of it. You fantasise about coming down with the flu the day before. In the end you have to do it. The presentation is a bit leaden. You get tongue-tied and confused when a key potential client asks a question.

An external contractor on a major project keeps pushing things in a direction you think isn’t quite right. But you find it very difficult to rein them in. It’s going over-budget, it’s not really what your firm needs. But you find it very hard to insist. The contractor is the specialist, they’ve got a lot of prestige in the industry. You don’t sell your ideas. You back down, even though you know you are right. It’s a nightmare.

The feeling ‘you shouldn’t put your head above the parapet, it’s asking for trouble’.

Causes

Fear of success is a problem. But it is an understandable one: there are three reasons why it can end up looking dangerous to succeed.

Fear of competition

‘I am not competing with the alphas – so they won’t see me as a target worth attacking…’

If I keep a low profile, they’ll ignore me, I’ll be safe.

A worry about provoking envy

There’s always a lot of envy circulating in the world. But being envied is (close up) a very unpleasant experience. It’s not like admiration.

So, to ward this off, one keeps one’s light under a bushel (one has come, unfortunately, to confuse success with boasting, arrogance, being smug.)

Performance anxiety

If I say I can do something and then it turns out I can’t, the women in the hall will laugh, I’ll get mocked in the pub. The consequences of trying and failing seem so risky, that on balance it feels prudent not to try at all.

Fixes

Dignifying the problem

Fear of success is a problem that can afflict capable people – and those you’d maybe least expect.

Harold Macmillan, the British Prime Minister from 1957 to 1963, was deeply affected by fear of success. He looked sure of himself; he could come across as smug. But he was terrified that his mentors – Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden – would see him as a threat and either abandon or humiliate him. He was always physically sick before making a speech in the House of Commons. In 1945 he had the support of a majority of Conservative MPs to run for leadership of the party. But he held back because it would have meant confronting those two men. It was twelve years before he finally took over.

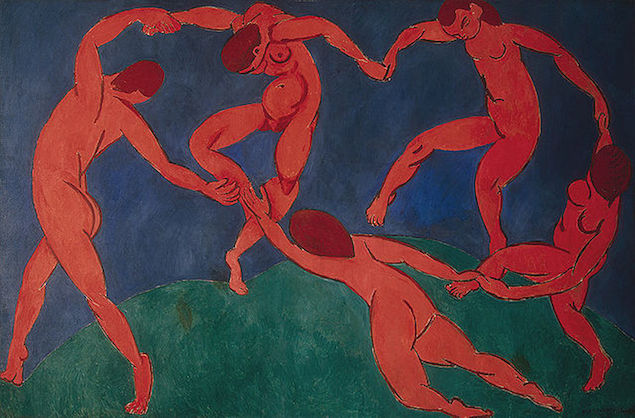

The French painter Henri Matisse eventually became loved around the world for his free, joyful style.

But he didn’t start out working like that. For years he was gripped by fear of success.

He worked in a deeply conventional way that gave no hint of his own character or preferences. He was inhibited by the anxiety that if he succeeded – if he produced the work he really wanted to – he would be criticised, especially by his own father who was a dour disciplinarian.

Examples like this remind us that fear of success is an honourable problem. They reduce panic and make it easier to admit one has this issue – which is a key step in addressing it.

Understanding where the fear has come from

The fear of success may have been acquired in unfortunate past environments where success really could be dangerous. You may have been in a school where people actually could get attacked by their classmates for doing too well in a test.

One might have grown up around an older brother who would react very aggressively if you ever seemed to be better at anything than him. If it looked like you might win at Monopoly, he’d kick the board over. If you were running faster than him, he’d trip you up.

An insecure father might endlessly tell stories of back-stabbing, betrayal, of how good people – like him – always get done over by the bad guys. At a young age this picture of the world (in which success is equated with scurrility) that gets lodged deep in your brain.

The fear was learned in particular past contexts; but the mind hasn’t quite caught up that in fact that your situation has changed; it’s following an old, tenacious pattern.

Understanding where the fear has started allows one to see that it doesn’t apply anymore. It may take many reminders of this to start to shift the pattern of thinking and feeling and make it more appropriate to where one is today.

Looking very carefully at the imagined danger: making oneself get serious and logical about the fear. What exactly do I think would happen if the presentation went well, if I insisted on my idea, if I sold a huge project to this client? One tries to visualise it in detail. Who does one fear would actually get upset. What might they do and say?

Then each element is carefully unpacked. What evidence do I actually have that people would react like that? don’t just ask the question. Write down a detailed answer. Use specific names, dates, describe the circumstances. Would Xavier actually feel slighted. How do I know this? If he did feel slighted, what problems would this actually bring? Could he block my career? If he wanted to sabotage the project, could he actually accomplish that? Could he reduce my salary package? If he tried who could I turn to? If the presentation went well, how would Paul, Fleur and Cassie actually react? Did they react badly when Tammy gave that excellent presentation on the Singapore market? Why would it be different for me?

11. Resistance to Learning

Selling can go wrong, because the seller is resistant to learning. We tend not to notice we have this problem, because we assume we like learning. We do. But the issue is about the kinds of things we might need to learn and our attitude to learning those particular things. We tend to have quite a restricted idea of what is learnable.

Dale Carnegie’s 1936 bestseller How to Win Friends and Influence People can easily provoke a negative reaction. One builds up a picture of someone cynically pretending to be friendly (when really they are not your friend at all). And of setting out to take advantage of you by following a few dark rules of the art of manipulating people.

We resist the notion that being warm, kind or charming are things that can be taught or learned. We’ve fallen prey to a Romantic belief that if it’s good, it can’t be learned.

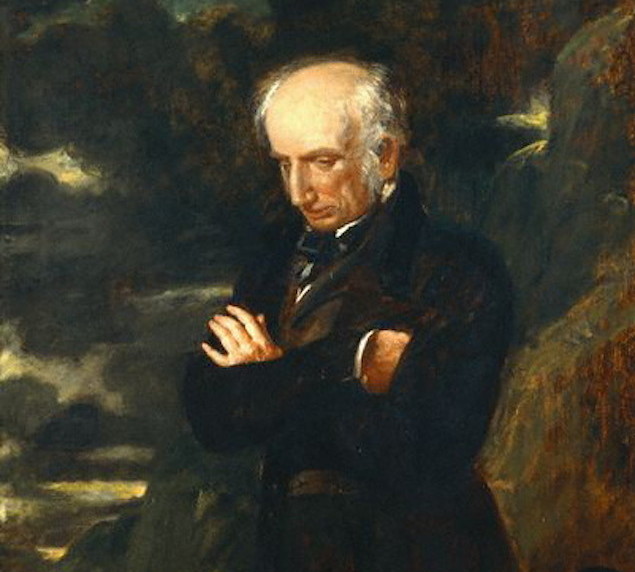

William Wordsworth – the leading figure of the Romantic Movement in England – defined poetry as ‘the spontaneous overflow of of powerful emotion.’ He was setting up an ideal that wasn’t meant to be confined to people writing sonnets.

He was promoting a general idea about how we should live. We should honour instinct and give the prestige to everything natural. Following rules and hiding your feelings were looked on with horror. It was an attitude deeply opposed to deliberately working out how to get someone to like you or studying how to influence. Wordsworth was a pioneer with his outlook, but he eventually had huge influence. And today it feels unfamiliar – and a bit sinister – to suggest that anything very personal could be learned.

Fixes

Aristocratic culture used to pay great attention to learning a wide range of things.

One might profitably learn how to stand behind a chair, how to have a conversation, how to hold a book, how loud to laugh, how to be witty, how to flirt and how to say no without giving offence. They took the view that our natural instincts could be improved by training and education. We may not need to learn precisely those things. It’s the more general attitude that matters: lots of little things can be learned and if you learn them it makes you nicer for other people to be around. It helps you succeed in the world.

Their view of what you might need to learn – can seem strange to us. But they were actually just continuing the long-running classical approach to education. That’s the view that the task of education is to improve nature. It takes as a starting point that we are not by nature well equipped to do all the things we need to. The classic approach took inspiration from tools and implements and all the technology they knew. They were particularly impressed by pulleys.

From Alberti, The Ten Books of Architecture

No individual is fitted by nature to lift a heavy statue. But with a neat artifice it becomes easily doable. Likewise, they reasoned, by nature we were not usually very adept at forming friendships, or explaining ourselves, or meeting strangers or telling anecdotes, or getting people to agree with us. We require artifice to rise to the challenge.

Learning how to do something doesn’t make us insincere. It just makes us better at doing it.

CONCLUSION: The dawn of capitalism

Driving in a taxi through Times Square at night, one might be mesmerised by the power of selling. A vast quantity of effort and ambition has been focused here. The entire square and (it feels) the sky is glowing with an urgent longing to entice us into buying a watch or a hamburger.

But not everyone is impressed. There might be a visitor from Europe who gets a bit annoyed by place. The sight of all these luminous adverts irritates them.

They’re not alone. They’re expressing a widespread attitude. Commerce, advertising and selling may be an unavoidable part of life, but it’s a low part. And the bigger and more powerful it gets (and in Times Square it seems very powerful indeed) the more it drags a whole society down: how can I be an honourable person in a society like this? This visitor can get very gloomy. They think wistfully of Chartres Cathedral, which they fondly remember visiting a few years ago. It’s also famous for light and colour.

They complain that Times Square is just commercial: it’s all about selling stuff. They see it as a sign of the failure of the modern world: in the past people built noble temples, here everything is business. It’s disgusting. Selling, they feel, is the root of the problem.

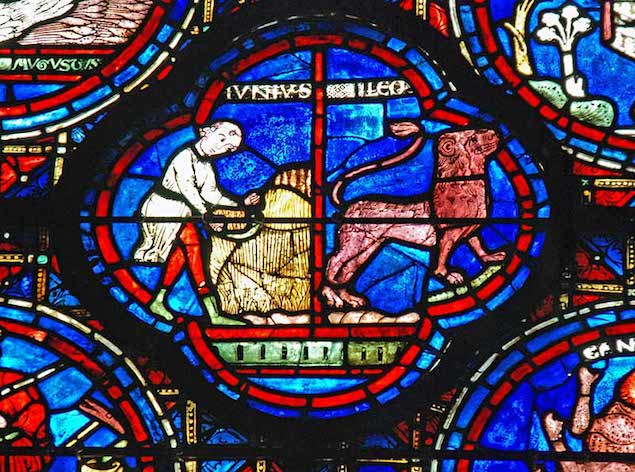

But this can’t be right. Because Chartres Cathedral was, in fact, a huge, highly elaborate, machine for selling. Amongst its more prominent advertising spaces are the round windows (which have been described as a crowning glory of French Culture).

An advert for the dignity of manual labour: threshing the corn can be boring, but Chartres is selling a consoling and accurate idea of it’s honourable place in the life of the community (which one is otherwise liable to lose sight of).

An advert for maternal kindness

Chartres was selling too: just at a more ambitious level. The Catholic Church was a corporation trading in ideas and experiences concerning forgiveness, love, duty, admitting one’s faults, being listened to and having one’s hidden merits appreciated. The Church wasn’t doing this simply in order to make money – these were its foundational convictions. But it was rewarded financially on a grand scale for supplying them.

The difference between Times Square and Chartres Cathedral isn’t to do with selling in itself. Both are devoted to selling. The difference is to do with WHAT is being advertised and sold. Times Square is selling chocolate, beer, cars, hamburgers and soft drinks. While Chartres Cathedral has a more elevated set of goods and services on offer.

We’re still at the dawn of capitalism. We can imagine Times Square in the future selling the important things: cures for loneliness, aids to forgiveness, things that help us be wise and kind. We don’t have to stop being devoted to advertising and commerce: we just need to engage with our higher needs and learn to profit from them.