Self-Knowledge • Emotional Skills

Humour

We know by instinct that humour is pretty important in relationships. But the reasons are often left a little vague.

It isn’t that we crudely want entertainment – there are enough comedians on TV. We don’t just seek relaxation. We want to find a way to be annoyed with, and criticise, one another’s most maddening sides without eliciting a drama, with a special kind of diplomatic immunity that is the gift of comedy. We need our partner, whom we love and yet find extremely difficult to live with, to understand what is so disturbing about their characters – and perhaps to want to amend them. That is what it means to get the joke.

We tend to regard funny people as just lucky, we interpret their comedy as an innate gift – something they just happen to have been born with. But in truth, being humorous is a skill, a teachable ability with a number of key moves behind it.

1. Exaggerating the Exaggeration: Benevolent Caricature

Spending time closely around someone inevitably exposes us to departures from normality or balance. Our partners are always a little crazy in areas – as we, naturally, are too. They might turn out to ring their mother at hourly intervals, clean the kitchen as if surgery were to be performed there, show a wounding inclination to invite friends along to the most private occasions or need to arrive at the airport six hours early.

We need to say something, but doing so directly and in a serious voice can be painfully counter-productive. Too often, the partner just swiftly feels attacked and refuses the insight.

This is where a certain kind of humour comes in. Exaggerating the exaggeration is a tool for criticising another person without arousing their irritation or self-righteousness. And the laughter we elicit isn’t just a sign they have been entertained; it’s proof that they have acknowledged an attempt to reform them.

What makes people irritating is that they have abandoned proportion, but they are prone not to recognise their abandonment when it is pointed out to them in reasonable terms. The art of crafting a joke therefore involves subjecting the troublingly disproportionate aspect of the other to an even greater, almost hyperbolic-degree of exaggeration – so that they are then forcibly jolted into a recognition of their loss of balance, while at the same time offered relief that they are not, of course, quite that bad.

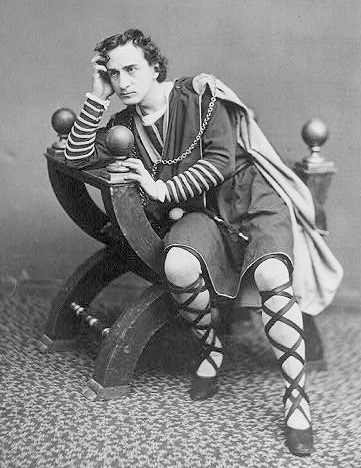

Suppose your partner is moody and preoccupied; they go in for excessively dark reflections and bleak assessments. One should search for an admired but extreme exemplar of this tendency. Shakespeare’s Hamlet, for example, might be a good name to assign to the partner: the Hamlet of domestic administration, the kitchen, or of the dinner table. To be called ‘Hamlet’ isn’t an insult. In fact, it’s very much like a comedic compliment. After all, Hamlet is commonly regarded as one of the most interesting and compellingly melancholic figures of Western literature. The name highlights a defect, but it is a great deal more bearable to be told that one is being like Hamlet – rather than that one is behaving ‘like a fucking teenager’.

A joking exaggeration picks up on a nice version of a failing, allowing us to introduce a painful truth via keyhole surgery – rather than blasting a hole in the other’s self-regard.

We can imagine responding to a partner who had become overly agitated about signs of dirt in the kitchen by theatrically over-playing the gravity of the issue, insisting: ‘Let’s commit suicide over the bread crumbs by the sink: you’re right, life is no longer worth living on these terms; We could nip round to the late night pharmacy and get a bottle of sleeping pills or take the bread knife to those larger veins in our ankles. Soon, we won’t have to worry about this messy world any longer. It could even be fun.’ One would during the speech need to be chirpy, relaxed, with just a playful twitch of the lips as one elaborated the technical details. As comedians know, tone is key.

The same basic move of exaggeration comes into play around strategically apologising for one’s own excesses. If we favour reaching the airport very early, we might cast ourselves as the Eisenhower of airports – alluding to the lengthy buildup and meticulous planning that the American general insisted upon (much to the irritation of Churchill) prior to the D-Day landings. The contrast is in our favour: we’re not suggesting booking a taxi eight months in advance. Still, we are signalling to our partner – in a way that is profoundly reassuring to them – that we acknowledge our abnormalities.

The comic move is to blow up departures from the norm to such manifestly absurd proportions, that even we or our partner can see them for what they always were: over-reactions. Comedy teaches us that the way to get someone to see that they have over-reacted is not to sound mature and reasonable. It’s to continue to pump up the problem until the over-reaction becomes so clear, so benign by its outsize dimensions that we start to laugh. We’ll have learnt to criticise through the humour of exaggeration – and our relationships will be a whole lot more secure as a result, when we allow our lover to magnify our failings into jokes.

As Oscar Wilde said: “If you want to tell people the truth, make them laugh, otherwise they will kill you.”

2. Mentioning the Unmentionable: Gallows Humour

Many things in relationships can feel too sad to mention: that we’ve only had sex twice this year (it might be July); that one of us is intermittently impotent; that one of us has a terrible temper, that the other sulks a lot; that one of us caught the other watching a lot of porn…

The most normal response is to say nothing, to skirt the issue. There can be a passive, vain superstition that if one doesn’t bring up an unfortunate fact, it could just fade away of its own accord. But not mentioning the sadness is also what lets it win its sapping victories over us. We start to be hemmed in by taboos; we suffocate from an earnest timidity around our griefs.

The strategy of Gallows Humour is different; it is usefully and gloriously defiant. It insists on mentioning the grimness, asserting control over it through mordant dry commentary. In the Middle Ages, a tradition arose of condemned people on the scaffold turning to the crowd and making a witticism about their situation. Freud recounts a man being led out to be hung at dawn saying, ‘Well, the day is certainly starting well.’ One aristocrat in the French revolution, on being ushered up to the guillotine (then a brand-new high-tech killing machine), looked up at its complicated workings and asked, ‘Are you sure this is safe?’

Gallows Humour is unsqueamish about looking bleakness straight in the eye. Rather than being slowly gnawed at by sideways glances at the truth, the gallows humorist insists they will not be silenced by it, they roll their sleeves up and grab it tenaciously. Our laughter is then a species of grateful relief at witnessing our most shameful secrets and fears handled with such reassuringly confident sang-froid.

A woman might respond to her man’s repeated impotence by remarking: ‘This will certainly save us a lot of money on condoms.’

Or one member in a couple with a history of getting into heated conflicts in ostensibly romantic contexts, might sit down in a beautiful restaurant and ask: ‘What do you think, shall we start our argument before or after we order?’

A wife whose husband has a porn habit might point to the computer ahead of a business trip and say to him knowingly, ‘Be sure to give it a good wipe before you bring it home. They’ll have good hand-wipes in Singapore.’

Gallows Humour resists the temptation to lecture or complain earnestly. It tells our partner that we are fully aware of the severity of certain problems with them, but suggests that we have the strength to endure them. It combines mentioning something we fear while bolstering our capacity not to be crushed by it.

We don’t need to be great comics to generate Gallows Humour. The technique follows a simple pattern. We should head directly for the saddest, most taboo sides of our relationship, remain utterly unflinching in front of them – but then deliver understated, breezy, unruffled responses to them, avoiding lapsing into any temptation to deliver a lecture, to be furious or bitter. Faced with a partner’s affair, the Gallows Humorist might say: ‘I hope you remembered to say that bit about your wife not understanding you.’ In response to the need to see a very troublesome mother-in-law to whom his wife is painfully close, a husband might say: ‘Such a pity the government doesn’t allow mothers to marry their own daughters; it would make things a great deal simpler…’

The male American Eel (Anguilla rostrata) passes almost its entire life – which can be up to twenty five years – without any erotic activity. It’s only when they are very old and about to die that they make it to the breeding grounds in the mid-Atlantic and finally get to have sex. ‘We make the Anguilla rostrata look like Don Juan,’ a man might drily say to his wife after yet another evening reading the newspaper side by side in bed – and she would smile back, both of them appreciating the attempt not to be defeated by the sadness of an unlibidinous marriage.

Gallows humour edges the worst facts bearably into a shared zone of conversation. It allows us to joke about what we could otherwise never say straight out. It is at heart an act of generosity; a gift to stop us being destroyed by silence.

3. Sharing Madness Safely: Sick Humour

A sick joke is one that deliberately runs counter to the collective standard (which is generally very reasonable and justified) of decent thought and action. The financier James Goldsmith once remarked that ‘when a man marries his mistress, he creates a vacancy.’ It’s a witty remark, but deliberately offends against ideas of love and fidelity. It flaunts the idea that that the libido should pay no attention to propriety.

Or there’s a story of a celebrated UK economist who arrived late at a dinner given by some well-to-do friends. They were in the middle of discussing how much money various individuals possessed. And when the economist sat down he heard them saying: ‘the so and so’s have four; but the X’s have nine; Y however has about 11.’ Unsure of the basis of comparison, the economist asked if they were discussing how many millions various people were worth. To which point his host gave him a withering smile and said, simply: ‘my dear fellow, we’re talking about rich people.’ The slightly sick aspect being the idea, current around the table, that someone worth 18 million pounds sterling would not remotely count as rich.

Strictly speaking we are supposed to find such remarks offensive, rather than entertaining. If, however, we do secretly find them funny it is because they tap into some part of our own minds that quietly relishes delinquent attitudes. We might never wish to announce to our friends that secretly we’d rather like to have a string of lovers or possess great wealth – and we know that these are hardly reasonable attitudes to guide our conduct in life. We censor ourselves but from time to time this powerful detail about who we are makes its presence felt. (A key fact about laughing at a sick joke is that it absolutely doesn’t mean that you would live by, or try to act upon, the view of life suggested in the joke.)

The fact is that we are all inevitably a bit mad in some direction or another: not through our own fault; it’s just that the strains in our development will almost certainly have led us into some pretty strange territory. We may be adept at keeping this well hidden nearly all of the time. But the person who knows us most intimately – our partner – will eventually encounter the more disturbed parts of our psyches (and we theirs). And a great deal depends on how we react to this. We can be shocked and disappointed. Or we can acknowledge that we too are a bit mad in some way – and possibly in the same way.

In the privacy of the couple, the ‘sick’ joke, that is the joke that runs against their nicer, more mature, more reasonable sides – allows the meanest most censored and impossible and frowned upon parts of who they really are – a small run around. It yields a modicum of psychic space to otherwise very lonely elements of who we are. It is extremely nice – and feels like a true gesture of love – to have the more mad bits of oneself acknowledged, in a kindly, funny way. We don’t admire or feel particularly proud about these things, but we do wish to be known and loved as the sometimes very strange people we actually are.

The ‘sick’ joke doesn’t just admit the existence of this area in a coy way, it momentarily presents it as obvious, even banal – that is as needing no defence.

‘Of course it might be nice to be an ambassador, only it doesn’t pay much – unless you got good at bribes.’ (to partner fantasies about backroom deals, precisely because they’d never actually do such a thing)

‘Shall we ask the waiter if he can offer cuninlingus instead of the zucchini?’ (to a partner who would never actually try to seduce the waiter but who is tickled by the idea).

‘We could have X – an annoying person at work – done in but, boringly, hit-men charge so much these days’ (when the partner couldn’t remotely take such a suggestion seriously, but is charmed that you float the idea as a joke.)

The sick joke holds a very lowly place in our cultural hierarchy of value, but it is at root a very important idea. It says: I can recognise this element in you (and sometimes in us) – without being frightened of it. And the reason I’m not frightened is because I’m very sure that you and I are in control. No, you’re not actually going to try to seduce the waiter, or have an associate murdered or turn down an ambassadorial post because it doesn’t provide enough access to the black market. Obviously in reality you won’t do any of these things – which is why I can safely and lovingly access the part of your mind that (madly but really) is a little bit turned on by them. It’s a joke precisely because it isn’t a plan of action. The ability to make sick jokes is a sign of health. And it is also a profound – though unfamiliar – act of love. Because it says this odd part of you isn’t a problem for me – I can be with you and like you and be your friend even here. Which is one of the kindest things another person could possibly say to us.

Conclusion

Jokes and comic insights don’t magically resolve the fundamental tensions of relationships. But they can make them hugely less oppressive. So often, the difference we face in love isn’t between bleak despair and unalloyed joy, but between bearable and unbearable degrees of difficulty – or (to speak metaphorically) between a ship that’s weathering the storm on one that is being driven onto the rocks.

Our lives are strung out between the merely imperfect and the truly awful. At best, we can move from seeing our partner as an idiot to viewing them as that far more tolerable alternative: a loveable idiot. The comedic sense isn’t the route to perfection, but it’s usefully promoting the good enough relationship which may be – by a long way – the best that’s available to us.