Leisure • Literature

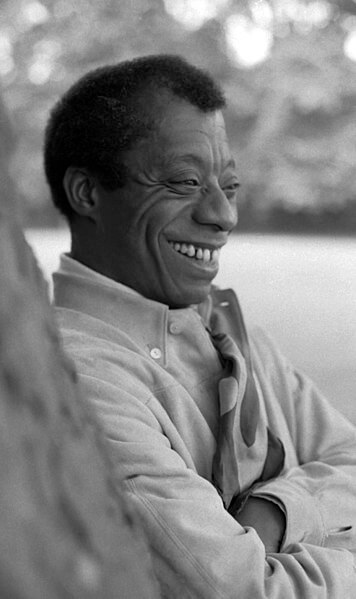

James Baldwin

James Baldwin was a novelist, essayist and activist whose writings on racism and the idea of self-acceptance in 20th century America challenged readers to investigate their innermost thoughts and beliefs.

He was born in Harlem, New York in 1924 at a time when racial segregation was rife in America. From housing to hospitals, everything was split between those for white people and those for black people.

Baldwin’s family had very little money and he was treated badly by his overbearing step-father. A precocious, intelligent boy, he spent much of his time alone in libraries reading books by Charles Dickens and Harriet Beecher Stowe.

At school, his large, sensitive eyes led to other children nicknaming him ‘popeyes’. He was bullied for being small and unathletic. Books and writing became his great place of refuge.

At 14, Baldwin became interested in the Pentecostal Church where his step-father was a preacher. He began to do his own preaching, several times a week, but gradually became disillusioned.

Reflecting on that period many years later, he described a community which had succumbed to its own form of discrimination.

“When we were told to love everybody, I had thought that that meant everybody,” he wrote. “But no. It applied only to those who believed as we did, and it did not apply to white people at all.”

His step-father died just before his 19th birthday and the funeral coincided with the onset of the Harlem riot of 1943. “As we drove him to the graveyard,” he wrote, “the spoils of injustice, anarchy, discontent and hatred were all around us.”

As a young man, Baldwin worked odd jobs and became friends with members of Harlem’s thriving artistic community, such as the painter Beauford Delaney.

He nurtured his ambition to be a writer, but also struggled more and more with the prejudice he faced on account of his race and his homosexuality.

In December 1946, his close friend Eugene Worth committed suicide by jumping from the George Washington Bridge. The incident traumatised Baldwin and convinced him to leave America. He feared that if he stayed in New York, he too would be driven to despair and take his own life.

He arrived in Paris in 1948 with only forty dollars in his pocket. He befriended a literary crowd, including writers he knew from New York, who helped to publish some of his earliest writing.

Whilst living in Paris, he drew inspiration from another great American writer, Henry James, and completed his first novel Go Tell It on the Mountain. A collection of essays, Notes of a Native Son, was published two years later, and by the mid 1950s, Baldwin had established himself as an important new voice.

However, his second novel, Giovanni’s Room, was less successful. His American publishers told Baldwin that its frank depictions of homosexuality would destroy his career and suggested that he burn the manuscript.

In 1957, he returned to America to report on the civil rights movement. He travelled widely in the American South and became close friends with key figures such as Medgar Evers and Martin Luther King Jr. His experiences in those years formed the basis for numerous essays such as ‘Down at the Cross’ and ‘My Dungeon Shook’ which won acclaim for their mixture of autobiography and incisive analysis on the realities of racial hatred.

As the civil rights movement grew in standing, so did the racially-motivated violence of those who opposed it. In 1963 Baldwin wrote to the Attorney General Robert Kennedy to criticise the government for failing to prevent outbreaks of violence in Birmingham, Alabama. He accused the President of not using “the great prestige of his office as the moral forum which it can be.”

At that time, protest was split into two distinct camps. There were those who believed in Martin Luther King Jr.’s nonviolent strategy of civil disobedience, and those who followed Malcolm X and his arguments in favour of aggressive resistance. Baldwin, however, trod a slightly different path.

He believed that racism began with the problem of self-deception. He saw American society as one which lied to itself about its past, where people were told not to think too deeply about themselves and others.

He described the mental barriers people place between the outside world and their innermost thoughts as being like a ‘dreadful, private labyrinth’ in which we become terminally lost.

Unable to properly confront their own true desires and beliefs, unable to recognise their own vulnerabilities and fears, they projected these anxieties onto an imaginary evil: a black community who wished only to be free from persecution.

In the essay ‘Down at the Cross;, he wrote: “It is galling indeed to have stood so long, hat in hand, waiting for Americans to grow up enough to realise that you do not threaten them.”

Baldwin emphasised the atrocity of what his friends and family had suffered, but he insisted that racism was a disaster for everyone. Time and again, he explained that racist beliefs only demonstrate how difficult people find it to understand and accept their own authentic selves.

He continued to write novels, essays and one stage play throughout the 60s and 70s, publishing his final novel Just Above My Head in 1979.

In 1970, Baldwin purchased a large country house in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, in the South of France. It became home for the rest of his life, a place where he liked to entertain famous friends such as Miles Davis, Harry Belafonte and Nina Simone.

He died in 1987, age 63.

Today, Baldwin’s work is remembered for its psychological clarity and the elegance of his writing.

Above all, his writing on love and the responsibility that love demands of people stands out as one of his great gifts to those who wish to reject intolerance and injustice.

In his 1964 essay, ‘Nothing Personal’, he writes about ‘the miracle of love’ that comes about when we can be honest with one another and trust in each other’s kindness.

This is not the love of pop songs or billboards, but a love inspired by the wounds we all carry and the tenderness we all crave.

‘The moment we cease to hold each other,’ Baldwin wrote, ‘the moment we break faith with one another, the sea engulfs us and the light goes out.’