Leisure • Literature

James Joyce

James Joyce is one of the most revered writers in the English language and a central figure in the history of the novel. He is still hugely important to us because of his devotion to some crucial themes: the idea of the grandeur of ordinary life, his determination to portray what actually goes through our heads moment by moment (what we now know as the stream of consciousness) and his determination to capture on the page what language really sounds like in our own minds.

Born in 1882, James Joyce spent the first 20 years of his life in and around Dublin and the rest wandering in and between the European cities of Trieste, Zurich, and Paris. In three decades, he published two books of poetry, a collection of short stories, a play, and three novels, all of them different in scope and scale, but sharing one thing in common: Dublin, a city he loved and hated. “Each of my books,” he once explained to a friend, “is a book about Dublin. Dublin is a city of scarcely 300,000 population, but it has become the universal city of my work.”

Joyce in Zurich, c. 1918

At the end of the 19th century, Dublin was the second city of the British Empire. Like his father, Joyce was fiercely opposed to Ireland’s status as a British colony, and supported the cause of Irish independence. Joyce was educated by the Jesuits, and early on at school, began to reveal his knack for foreign languages. By the time he arrived at University College, Dublin, Joyce was writing book reviews, poems, and short stories, but he also needed to find a career. He tried medical school in Paris, but spent more time in brothels and bars than the library.

In 1904, he met a young woman from Galway named Nora Barnacle, who was uneducated but highly erotic and compelling to Joyce. When she first saw him she thought he was a nordic seaman, with ‘electric blue eyes, yachting cap and plimsolls. But when he spoke, well then, I knew him at once for just another worthless Dublin boaster trying to chat up a country girl.’ But she fell in love with him and remained devoted through all their difficult life together.

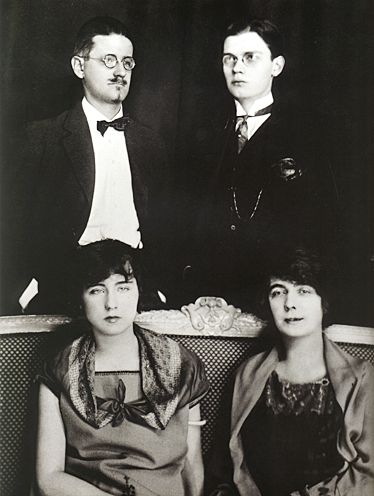

James Joyce, Giorgio Joyce, Nora Barnacle and Lucia Joyce in Paris, 1924

After a few months, she agreed to follow him to Europe for a self-imposed exile, free from the morality of the Catholic Church and the subjugation of the British Empire. They eventually landed in Trieste, an Austro-Hungarian port town where they would spend the next 10 years, raising two children, both of them given Italian names (Lucia and Giorgio). Joyce eked out a meager existence as a language teacher at the Berlitz School and translating Irish writers like Yeats and Oscar Wilde into Italian.

1914 turned out to be Joyce’s year of breakthrough when a publisher in London finally decided to bring out his book of short stories, Dubliners which had been rejected 22 times, and the American poet, Ezra Pound, arranged to get his novel, A Portrait of the Artist, serialised. This was followed by the serialisation of Ulysses in 1918, the book which made Joyce’s name around the world.

Joyce’s grave in Zurich

For the next 23 years, Joyce’s reputation grew and he took his experiments with language and literary form ever further – until his unexpected and sudden death in Zurich in 1941. He was buried in Fluntern Cemetery, just near Zurich’s main zoo.

1. The grandeur of everyday life

Joyce’s principle work Ulysses is named after the most dramatic adventure story the ancient Greeks handed down to Western civilisation. It is seen as a pinnacle of high culture and tells the story of the long wanderings of the hero, Ulysses, on his journey back from the siege of Troy to Ithaca, his home. But the major character of Joyce’s novel is not a warrior king or a great hero. He is, instead, a very flawed, quite kindly and quite foolish man called Leopold Bloom. He works as a minor player in the advertising industry, he is married (but his wife is having an affair), he’s been sacked from a string of jobs and he is very much given to daydreaming about all the things he would love to go right in his life – but which we know won’t happen. He farts, he likes looking at women in the street, he dreams of winning competitions in weekly magazines and of owning a cottage by the sea. Being Jewish, he is a bit of an outsider in Catholic Dublin and there are various little humiliations which he has to put up with all the time. He is very unlike a traditional hero, but he is representative of our average, unimpressive, fragile – but rather likeable – every-day selves.

Joyce lavishes attention on Leopold Bloom. He treats him a deeply worthy of respect and immense interest, he’s someone (Joyce suggests) we should learn from and try in certain ways to be like – just as in the ancient world, Ulysses was held up as an inspiring model of resourceful and brave conduct.

Joyce’s drawing of Leopold Bloom

We follow Bloom for a whole day as he wanders around Dublin, we see him having lunch, buying his supper, drinking coffee and cocoa; he worries about his relationship with his wife and his daughter, he goes to work, he listens to someone singing, he has various conversations. Joyce is saying that the apparently little things that happen in daily life (eating, feeling sorry for someone, feeling sorry for oneself, putting the washing on the clothes line, getting embarrassed) aren’t really ‘little things’ at all. If we look at them through the right lens they are revealed as beautiful, serious, deep and fascinating. Our own lives are just as interesting as those of the traditional heroes, but we’re less good at appreciating them. The helpful lens is supplied initially by Joyce’s novel, but ideally we should internalise it and make it our own: we should accept ourselves as minor legitimate heroes of our own dignified lives.

2. Stream of Consciousness

Traditionally, novels (like most films today) shows us people speaking in well-formulated, clear and relevant sentences. And we tend to suppose (without really thinking about it) that this is a fair reflection of their inner life. They speak the thoughts and feelings they have.

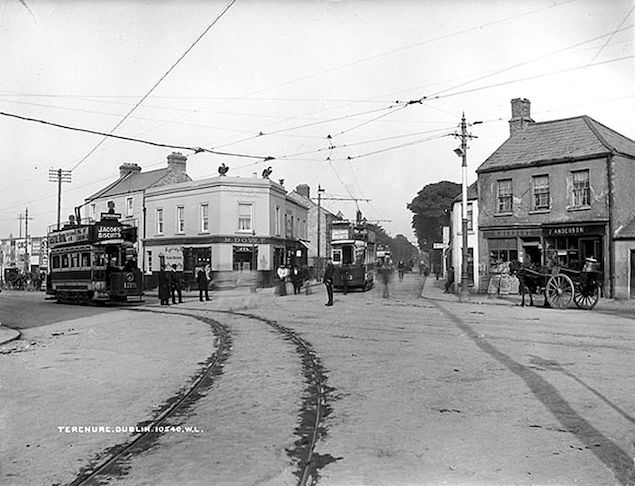

But this isn’t Joyce’s way at all. Joyce takes us into our minds and tries to show us what thinking really sounds like. At one point in Ulysses Leopold Bloom muses on the cycle of life while he’s watching the tram cars and people in the street.

Trams passed one another, ingoing, outgoing, clanging, clanging. Useless words. Things go on the same day after day: squads of police marching out, back: trams in, out. Those two loonies mooching about. Dignam carted off. Mina Purefoy swollen belly on a bed groaning to have a child tugged out of her. One born every second somewhere. Other dying every second. Since I fed the birds five minutes. Three hundred kicked the bucket. Other three hundred born, washing the blood off, all are washed in the blood of the lamb, bawling maaaaaa.

It’s a strange – and yet actually very familiar – muddle of high and low concerns, he’s thinking about birth and death and the random shortness of life and the idea of religion (‘washed with the blood of the lamb’ is a line from a Christian hymn) but also thinking about that he fed some birds, the ordinary rhythms of daily life, the noisy trams and the fundamental oddity of language – in which sounds we make with our mouths stand for things in the world.

If we could slice the top off people’s heads and get a view into the diverse thoughts that circulate and cut across one another – contradicting and confusing one another – we’d have a much more accurate picture of our fellow humans. And one radically at odds with the image we typically have: that people are psychological monoliths with clear, definite and fixed views who are very clear what they believe and care about (and don’t care about). Joyce – like other modernist describers of stream of consciousness thoughts and feelings – is suggesting that if we knew more about what others and ourselves really thought and felt we’d have a clearer sense of what it means to be human; and we’d also perhaps be slower to anger, quicker to forgive; we’d love more and hate less. We’d be more curious about the apparently strange byways our own minds – and those of others – are endlessly following.

3. The Wonder of Language

The more Joyce went beneath the surface of our utterances to reveal the cacophony of our minds, the more he felt the need to twist and remould language itself to capture how we sound to ourselves.

In his last and truly puzzling novel, Finnegans Wake, Joyce decided to create his own version of English, a “tower of babble,” by mixing together bits and piece of more than 40 languages. Sometimes the words on the page look entirely foreign, but if you sound them out, you can often find the sense. “Hereweareagain” means what it says: it’s just that the words are jammed together, to reflect the speed of the mind in action. Joyce went in for many “portamanteau” words, two or more words stuck together to create a new one. A “funferall” is a fun funeral or a fun for all: a bisexcycle is a bisexual or a bicycle for sex. He twisted prestigious names: so Shakespeare becomes Shakehisbeard and Dante Alighieri Denti Alligator.

A drawing of Joyce by Djuna Barnes from 1922, the year in which Joyce began writing Finnegans Wake

The plot, in so far as there is one in Finnegans Wake, is about a man called Tim Finnegan, who falls from a ladder, dies, and comes back to life when someone spills whiskey on his face during the wake. It is intended as a universal story about the fall of mankind, and the character of Tim Finnegan is also meant to be, simultaneously, Adam, Noah, Richard III, Napoleon, and the Irish nationalist Charles Parnell. There is indeed a plot in this book, but it is not one, Joyce explained sarcastically, that can “be rendered sensible by the use of wideawake language, cutanddry grammar and goahead plot.”

In attempting to be completely faithful to real life in all its true confusion and complexity, Joyce ended up writing a book that is fascinatingly, instructively unreadable. The fourth sentence of the first chapter runs: ‘Rot a peck of pa’s malt had Jhem or Shen brewed by arclight and rory end to the regginbrow was to be seen ringsome on the aquaface.’ It’s a reminder of how much fiction, when it seems logical and understandable, is always necessarily a drastic foreshortening of what is actually going on in the world and the minds of characters. Joyce pushed one possibility of the realistic novel as far as it could go – into a realm as mysterious, haunting and perplexing as the dreams of a stranger.

Conclusion: What is art for?

Joyce spent the greater part of his life writing. What was he hoping to achieve through his art? What is art for?

In The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Joyce gets his spokesman Stephen to have a go at spelling out an answer. He follows a surprisingly traditional route, using two terms from the medieval philosopher St Thomas Aquinas.

Joyce in Zurich in 1915

The first is Integritas: This means that an artist is someone who attempts to grasp with unusual vigour the true integrity and identity of what is being studied. It might be a tree, a moment of history or the life of a fictional character in 20th century Dublin. We don’t normally do this, we don’t really concentrate on what a person is saying or doing, or what objects around us really are and look like – we don’t normally isolate and study carefully. Art has the job of doing this for us, and teaching us to do so habitually.

The second step for an artist is to bring Claritas – or clarity: which means shining the light of reason into the murkier parts of experience and life.

The paradox is that Joyce did just this, but in his attempt to be clear about what being human is actually like, he created works which are in places utterly baffling to the reader in a hurry. That shouldn’t surprise us too long though. Art – as Joyce sees it – should be a corrective to our natural, but dangerous, blindness and inattention, to cliché and over-rapid summary. If it sometimes puzzles us, we know – says Joyce – that it’s doing its job properly; it’s re-awakening us to mysteries we have too quickly grown blind to.