Work • Utopia

On the Desire to Change the World

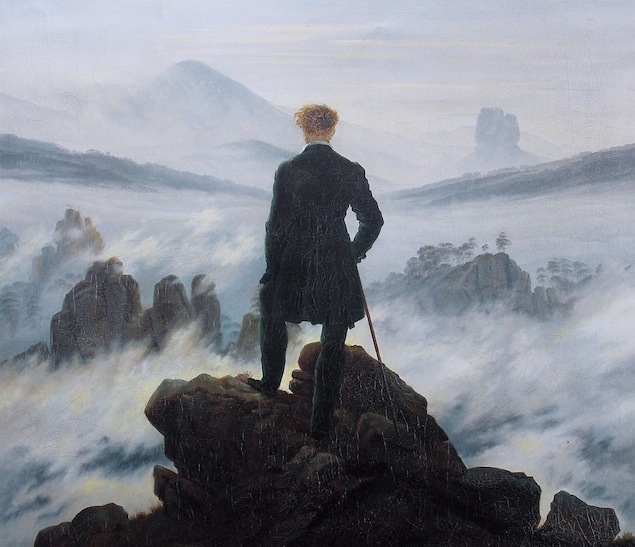

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818)

The world needs changing in all sorts of urgent ways: the great question is how to do it. The most popular and appealing answer has long been that one should try to write a book, retreat to a mountain-top, lay down one’s thoughts with passion and cogency, try hard to sell as many copies as possible and wait for change to emerge.

Immense prestige has surrounded this activity for the last 200 years at least and it can seem, from a distance, that it has been deeply successful as well. Some books have undeniably made a splash (Das Capital, Thus Spake Zarathustra, Silent Spring, The God Delusion…)

And yet, big book sales aside, the world has continued to change a lot less than it should, remaining surprisingly committed to its familiar wicked ways, despite the existence of so many wonderful, thoughtful, revolutionary and popular books.

That’s because we’re missing an insight. Books – however marvellous they may be – cannot, on their own, change very much, and the widespread belief that they can, strongly holds back progressive causes and the effectiveness of enlightened minds.

A book is of course an ideal place to lay down an ambition, sort out one’s thoughts and gather a constituency. But that’s about it. A book on its own cannot bring about real change because the world as it currently stands isn’t held together simply by ideas: it is made up of laws, practices, institutions, financial arrangements, businesses and governments. In other words, its muscles are made up of institutions and therefore, the only way to bring about real change is to act through competing institutions. Revolutions in consciousness cannot be made lasting and effective until legions of people start to work together in concert for a common aim and, rather than relying on the intermittent pronouncements of mountain-top prophets, begin the unglamorous and deeply boring task of wrestling with issues of law, money, long-term mass communication, advocacy and administration.

In the Republic, Plato confessed to a profound and melancholy understanding (gathered from bitter experience) of the limits of intellectuals, when he remarked that the world would never be set right until, in his words, ‘philosophers became kings, or kings philosophers’. By which he meant that thinkers should stop imagining that ideas can change reality and recognise that only institutions, ‘kingship’ in this context, have any chance of working a proper influence on the world.

How do you change this?

Partly, the problem comes down to temperament. The types who have good ideas generally aren’t good with money, they get bored with details, they may have the spiky characters which mean they can’t get on with other people, they don’t like going to the office or sharing the platform. Our collective ideal of the free thinker is that of someone living beyond the confines of any system, disdainful of ‘boring things’, cut off from practical affairs and privately perhaps rather proud of being unable even to read a balance sheet. It’s a fatally romantic recipe for keeping the status quo unchanged.

[image-sidebyside]

[/image-sidebyside]

Shelley/Nietzsche: both wanted to change things, neither was too good with administration

As a result those with an interest in changing things have typically run what are, in effect, cottage industries. They may have managed to secure a brief spike of fame for themselves, but they haven’t been able to place their achievements on a stable footing, consistently replicate their insights or bridge their weaknesses. Sole authorship cannot be a logical long-term response to solving the complexities of the most significant global issues.

The modern world is not, of course, devoid of institutions, just most of them are the wrong sort. The mightiest institutions are commercial corporations with unparalleled power, scores of employees, a ruthless focus on profit and a single-minded interest in the material side of life.

There’s one exception to this that change-aspiring thinkers should spend some time studying: religions. What makes religions distinctive and inspiring in this context is their genius for getting organised. Whatever one thinks of their ideas (this news outlet is deeply secular), religions are not just about ideas, unlike what atheists sometimes make the mistake of thinking (taking them on at the level of ideas is therefore doomed because they are, in fact, first and foremost institutions). Religions are enormous agglomerations of people with a relentless appetite for administration and bureaucracy. So for example, Christianity, Judaism and Buddhism have all managed to stick around for a very long time because they have related larger ideas about the salvation of mankind to such ‘boring’ activities as running banks, legal teams, community centres, orchestras, youth movements, weekend retreats, radio stations, lecture halls and clothing lines.

© Flickr/Maciej Bilas

They start them young

Plato’s hope that philosophers might be kings, and kings philosophers, was partially realised many hundreds of years after he expressed it, when in 313 A.D., thanks to the efforts of Emperor Constantine, Jesus took up his position at the head of a gigantic state-sponsored Christian church and thereby became the first quasi-philosophical ruler to succeed in propagating his beliefs with institutional support.

An intellectual making friends with power

A similar combination of power and thought can be found in all the major religions, alliances which we can admire and learn from without subscribing to any of their ideologies.

The problem with the world today isn’t that we lack good ideas. We have great, sound, beautiful, enlightened ideas to last us a hundred generations. Enough new books! We don’t have to work stuff out. We have to make what we already know very well more effective out there. The urgent question is how to ally the very many good ideas which currently slumber in the recesses of intellectual life with proper organisational tools that actually stand a chance of giving them real impact in the world.

To recap: if you want to have an impact and affect society in the long term, writing things down and giving them to other people to read in the way we do in the contemporary world is fated to be horribly ineffective – for reasons that only one group of people seem properly to grasp: the religious. From a completely secular starting point, it can be worth studying religions to learn how to alter behaviour.

Repetition

It’s tempting to believe that people don’t do the right thing because they don’t have the right ideas. But in truth, we already have so many nice ideas at the back of our minds; the problem is, we don’t act on them, and we don’t do so because, at key moments, we lack reminders, motivation and encouragement.

© Flickr/Rajarshi Mitra

Too often, social reformers have implicitly believed that if you just tell people what is right once, all will be well. However, it seems we need to be told things hundreds of times over long periods before they have any chance whatsoever of affecting how we actually behave. Religions are therefore rightly obsessed with repetition. Three or five or ten times a day, they’ll tell us more or less the same thing, because they know that what seemed really convincing at nine in the morning will have entirely gone by evening. Religions have calendars that split time up into tiny segments, each of which has some divine truth tagged to it.

Sometimes we see a film that makes us want to change ourselves and the world. We leave the theatre vowing to reconsider our entire existence in light of the values shown on screen. And yet by the following evening, after a day of meetings and aggravations, our cinematic experience is well on its way towards obliteration, just like so much else which once impressed us but which we soon enough came to discard: the night sky we saw on the motorway, the line of poetry a friend told us about, the sweet feelings we had after hanging out with a child…

There is arguably as much wisdom to be found in the novels of Tolstoy as in the Bible – but the big difference is you’re only meant to read Tolstoy once in your life, if that, whereas a committed Christian or Jew might go back to the Bible every day.

Ritual

Portrait of William Wordsworth, Benjamin Robert, 1842

A ritual is a repeated, communal event connected up with private individual evolution and enlightenment. The secular world is deeply suspicious about, and inept with, rituals. It thinks of them as ‘fake’ and too bossy.

But religions have rituals for everything. All the key moments of life are ‘ritualised’: that is, they are put onto a public footing and given an outward shape.

Take the feeling of relief, gratitude and pleasure that it’s finally springtime. Lots of secular writers have written about this, Wordsworth for one. But the problem with Wordsworth is that – once university is past – we all forget to read him.

There’s no such danger of forgetting spring exists if you’re a committed Jew, however, because you have a ritual in its honour in your diary. This month sees the celebration of the ritual of Birkat Ilanot, which involves the faithful being asked to come out of their houses and go into the fields to say prayers from the Talmud at the foot of blossoming trees.

It’s only one of religion’s many beautiful and useful rituals. We need rituals to foster and protect emotions to which we are sincerely inclined but which, without structure and active reminders, we will be too distracted and undisciplined to make time for.

Chartres Cathedral

The modern world has lots of interest in beautiful things: there are elegant boutiques, celebrated designers, fashionable artists, famous singers and lauded buildings… And simultaneously, there’s a high respect for important ideas and concepts.

But what’s lacking is any particular drive to try to unite these two elements: to unite beauty with truth, that is, to try to make the most important concepts and ideas attractive and seductive (and therefore far more effective) through the medium of art.

This is what religions have, for their part, excelled at doing. They’ve realised that if you put down an important idea on paper in somewhat pedestrian prose, it won’t have any lasting or mass impact. They’ve therefore, over their history, engaged the most skilled artists to wrap their ideas in the coating of beauty. They have asked Bach and Mozart to put the ideas to music, they have asked Titian and Botticelli to give the ideas a visual form, they’ve asked the best fashion designers to make nice looking clothes and they’ve asked the best architects to design the most impressive and moving buildings to give the ideas heft and permanence.

This is rarely done now. In the modern world, the people who make music are not particularly in touch with the people who have ideas. Therefore many songs, even the great ones, are rather banal at the level of theme, however catchy and inspiring they are in their melodies. Similarly, fashion is seen as an exciting but rather frivolous activity disconnected from anything as grand as changing the world. Serious people rarely think that what they’re wearing may have a grave impact on how what they’re saying is received – something that would deeply surprise a Catholic bishop getting his stunning robes ready for a service. And architects are now rarely invited to put up buildings just in order to glorify and beautify an idea – as the builders of Chartres Cathedral did.

The world isn’t being changed as effectively as it should be because many of us are forgetting to study the tips that can usefully be drawn from religion. We should use the history of religion to inform us about the role of repetition, ritual and beauty in the name of changing how things are.