Work • Sorrows of Work

On Professional Failure

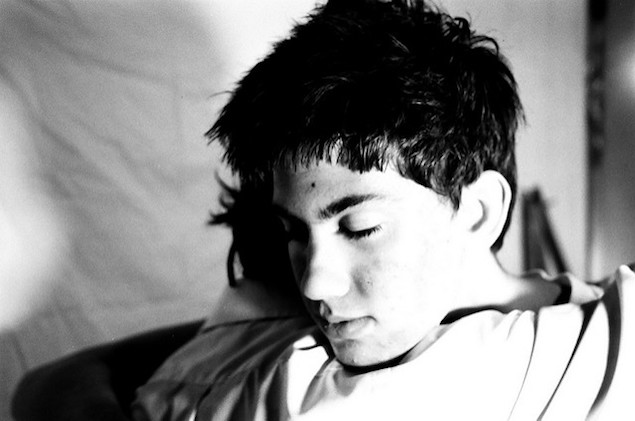

To survive in the pressured conditions of modernity, we have to get very good at self-criticism. We have to make sure that there is nothing our worst enemies could tell us that we have not already fully taken on board: we must become masters of self-hatred. We must behold our own mediocrity without sentimentality or favour; we must allow paranoia to triumph over ease and complacency. Yet so skilled may we become at these manoeuvres, our victory is at risk of miscarrying. In response to certain professional setbacks, we may grow to despise ourselves to such an extent, we eventually develop difficulties getting out of bed. In time, we may even conclude it might be best just to do away with ourselves.

To attenuate the chances, we should occasionally explore an emotional state of which the ambitious have an understandable tendency to feel extremely scared: self-compassion. Kindness to ourselves can feel like an invitation to indulgence and then disaster, given how much of our success we attribute to anxiety and self-flagellation. But because suicide has problematic aspects too, we should concede the value of calculated moments of self-care.

For a time, until we are stronger, we should be courageous enough to adopt a more generous perspective on ourselves. We may perhaps have failed, but we have not thereby forfeited every claim to sympathy and compassion. We were defeated not merely because we were cretins, but also…

– Because the task was very hard

We fell so readily and heedlessly in love with success, we failed to notice the scale of the challenges we had set ourselves. There was nothing ultimately very normal about what we were trying to achieve.

– Because we are crazy

With no pejorative intent in mind, just as everyone is and cannot avoid being, we are crazy. Crazy for only intermittently knowing how to act with reason, for responding to situations through the distorting prisms of our half-forgotten, always troubled childhoods, for failing to understand ourselves or others properly; for losing our grip on our tenuous reserves of patience and equilibrium.

The Christian notion of original sin emphasises that everything human will always, by necessity, be radically imperfect. Our primal ancestors – Adam and Eve – made an error that cast its shadow over the whole of human history. The idea doesn’t need to be believed for us to recognise its consoling implications: our lives have gone wrong not because of this or that mistake on our part but because of a far more profound and basic flaw in our species – an endemic stain that can never be put right.

– Because failure was always the more likely outcome

We hear so much about success stories, we imagine – quite naturally – that they must be the norm, and forget that they are in truth the freakish oddities and – hence – unhelpful, maddening markers for comparison.

We would need, but are so rarely able to achieve, a statistically more reliable impression of what the lives of most other people are like – which would teach us the normal pattern that lives adopt. Rather than the gallery of heroes we are exposed to, we need regularly to witness ordinary follies: people who cling to mistaken assumptions, take wrong turnings, step carefully away from what later turn out to have been the best options, commit themselves enthusiastically to errors, are ignored by most and hated by a few, never enjoy true fulfilment in love, are filled with regrets around their families and die with a great deal of bitterness and pain.

The universal plight is fundamentally a sad one and yet we insist on feeling privately ashamed of what ought to be one of the most basic publically-recognised truths about the human condition: that we fail.

For a long time, our societies cruelly, sentimentally insist the opposite, that we can and will all win. We hear about resilience, bouncing back, never surrendering and giving it another try. Not all societies and eras have been as merciless. In Ancient Greece, a remarkable possibility – as alien as a trimerene to our own era – was envisaged: you could be very good and yet, despite everything, mess up. To keep the idea at the front of the collective imagination, the Ancient Greeks developed the art of tragic drama. Once a year, at huge festivals in the main cities, all the citizens were invited to witness stories of appalling, often grisly, failure: people who had broken a minor law, made a hasty decision, inadvertently slept with the wrong person and then suffered extremely swift and disproportionate ignominy and punishment. Yet the responsibility was far from belonging to the tragic heroes alone, it was the work of what the Greeks called ‘fate’ or ‘the Gods’, a poetic way of insisting that destinies do not reasonably reflect the merits of the individuals concerned. We were to leave the theatre shorn of easy moralism, sympathetic to the victims, afraid for ourselves.

Modern societies have a harder time of all this: they appear unable to accept that a truly good person may not succeed. If someone fails, it appears easier for them to believe that they weren’t – after all – good in some way, this conclusion defending us against a far more disturbing, less well-publicised and yet far truer thought: that – in fact – the world is very unfair.

We all stand on the edge of tragedy – in societies reluctant to offer us sympathetic playwrights to narrate our stories.

– Because we envied the wrong people

We began to envy them because they seemed so like us and we wished so ardently to be them. Our sense of a basic equality unleashed competitive agonies. But though from a distance, these successes did indeed seem very much like us, beneath the surface, they evidently possessed a range of skills we lack: they may have had highly unusual brains adept at synthesising vast amounts of financial data in ingenious ways. Or they were driven to work eighteen hours a day or had a ruthless streak, which we were fundamentally not capable of or interested in. The haunting thought – why them, why not me? – should no longer invite simply self-torture and competitive panic, but should edge us towards an unfamiliar feeling of admiration.

There might truly be big differences between oneself and the envied person. One wasn’t ever really their equal. It isn’t hence just laziness, or some kind of persecutory force that explains our present relative situation. When viewed dispassionately, certain accomplishments are truly beyond us. We should become appreciative spectators, rather than disappointed rivals, of those spectacularly unusual beings who have accomplished great things.

– Because we judged ourselves by what we do – not what we are

The messages we imbibed through education and work said otherwise, but we are – in the end – not our achievements alone. Status and material success are bits of us – yet there are others. Those who loved us in childhood knew this and, in their best moments, helped us to feel it. We need to adopt a parental relationship with ourselves and rehearse the internalised voices of all those who have nurtured us without demands.

True reassurance isn’t to say that one’s plans may well work out; it is to insist that one’s human worth is not on the line even if they don’t.

– Because we never had a chance to work out what we really wanted to be

We were rushed, we were sold a Romantic idea that we would find our vocation, something deep in our nature that would guide us to an ideal job for us – one that we were perfectly fitted to by nature and that would make us wholly happy. The trouble was, there was no time and we never got there.

We should have taken weeks away from everything and everyone and given ourselves over to a solitary thinking, free from the pressures of pleasing others. Working out what to do was hard, not because we were stupid or self-indulgent, but because our decisions had to be built on scattered and very imperfect bits of evidence. Confused shards of information were scattered across our experiences. What, in fact, ever were our strengths? There were moments of boredom, excitement, things we coped well with, things that were intriguing for a while and then neglected: all of these needed to be located, decoded and interpreted and pieced together. Finding accurate answers would have meant building up high levels of self-knowledge. In an ideal culture there would have been many novels which took this critical period of career direction as their dramatic focus; with the central character emerging from a heroic journey of enquiry with a clear conviction that they should – perhaps – go into events management, the civil service or ophthalmology.

Instead, the big, consequential choices around career occurred under inescapably adverse conditions. Ultimately we were attempting to make decisions for someone we couldn’t possibly fully know: ourselves in an unimaginable future.

– Because we are very tired.

It feels familiar to attribute our worst panics to solidly-grounded facts and ideas.

Yet sometimes the reasons are more humbling and more open to resolution: we are exhausted. The generous parent knows, when faced the tantrums and furies of an infant, that it is not always worth attempting to reason them out of their grief. It may just be the case that one should guide the child to bed and hope very much for a long, restful night. We may need to act as guardians to our own bruised and furious inner child.

Self-compassion is different from saying that we are innocent. It means trying to be extremely understanding around the full range of reasons why we have failed. We have been imbeciles no doubt, but we deserve to exist, to be heard and to be sympathetically forgiven nevertheless.