Relationships • Mature Love

Other People’s Relationships

A question that rarely leaves us alone in love is: what exactly are other people’s relationships like?

The question is far from disinterested sociological curiosity. What we urgently seek to know is: are other people in as much trouble as we are? After a furious row over nothing very much at eleven at night or after yet another month that has unfolded with almost no sex, we wonder how statistically normal our case might be – precisely because it threatens to feel like a unique curse.

Most of us have a handful, maybe four or five, relationships that we know and keep in mind as standards of what we understand by normality. Perhaps we met these couples at university or they live on the street and are at a comparable stage of life. Without knowing they are playing this role, these sample couples function for us as our secret spirit level of love.

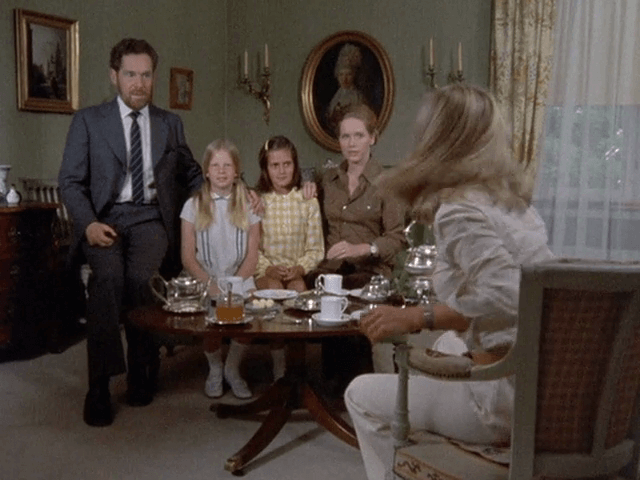

At tennis, we notice how kind they are to one another; as well as how energetic and lithe they remain. Over dinner, we note how much respect they show to their respective opinions. In the taxi on the way home, we spot the tender way they hold each other’s hands. And, naturally, we feel both highly abnormal and very wretched as a result.

But our assessment of our love stories suffers from a basic and unfair asymmetry: we know our own relationships from the inside but generally only encounter the relationships of others in heavily edited and sanitised form from the outside. We see other couples chiefly in social situations where politeness and cheeriness are the rule. We take on trust their blithe summaries of their lives. But we don’t have access to footage from the bedroom, the uncut transcriptions of their rows or their raw nighttime streams of consciousness.

However, we have all this and more about ourselves. We can’t help but be intently aware of our own relationships’ sorrows and absurdities: the cold silences, harsh criticisms, furious outbursts, episodes of door slamming, bitter late night denunciations, simmering sexual disappointments and times of aching loneliness in the bedroom.

Because of this asymmetry, quite understandably, we come to the conclusion that our own relationships are a great deal darker and far more painful than is common. In times of distress, we fling a definitive accusation at our partner: ‘no-one else has to put up with this.’

We need, to be fairer on ourselves and our beloveds, to create space in our minds for the scale of our ignorance. We simply don’t know. We are lacking data. We owe ourselves a richer picture of love than we have yet secured. This isn’t prying or cruel, we just need to better understand the true nature of the task we’re undertaking.

The truth is that misery – or at least some kinds of very serious longing and scratchiness – is the rule, far more than public sources will ever admit. It’s not that we as a couple are strangely awful or damned: it’s that relationships themselves are an essentially and inescapably difficult project.

Part of the reason we get it so wrong is that we have the wrong kind of art: the movies we watch are oddly coy, the novels don’t tell it how it is. It’s a marker of the problem that we almost never leave a cinema or close a novel thinking: that’s just like my life.

The dominant emotion of most relationships is ambivalence; that is, a complex mixture of love and hate, contentment and confinement, loyalty and betrayal. Most loves are too good to leave, yet too compromised to assure ongoing profound contentment. They subsist in a grey zone, where moments of joy bleed into stretches of melancholy, where at points we sob and are certain the partner has ruined our lives and then, the following morning, assisted by sunshine and black coffee, recover a feeling of things being basically fine.

If we could properly see – via tenderly accurate films and novels and chats in group therapy or with older honest couples – the reality of pretty much any relationship we might arrive at a surprising and deeply heartening conclusion: that our own relationship is – in fact – two things above all: very normal and quite OK.