Self-Knowledge • Melancholy

Our Tragic Condition

When it comes to our sense of who does and doesn’t deserve punishment, we tend to operate with a simple dichotomy: either someone is guilty, and therefore must pay for their misdeeds, or they are innocent and should be allowed to walk free. Off the back of this divergence, we also know how to apportion our sympathies: the innocent merit our concern, the blameworthy have it coming to them.

And yet when we examine a great many lives from close up, a more troubling reality comes to light. In scenarios we know as ‘tragic’, the apportioning of blame becomes impossible. A person may have done something quite wrong: they ended a relationship tactlessly, they had an affair, they lost their temper and said words they shouldn’t. Their behaviour has clearly earned them some form of comeuppance.

But it’s the sheer scale of this eventual comeuppance that can tip due process into tragedy. In certain cases, after an affair has ended tactlessly, the rejected party doesn’t merely weep and take their leave; they may seek to destroy their ex’s reputation, post untrue allegations online and get them discredited among all potential employers. Or, equally tragically, they may kill themselves – exacting a life-long burden of guilt. Alternatively, a fleeting hot-tempered moment at work one afternoon might mean that someone is hauled before a tribunal, sacked for gross misconduct and can never find another job again, prompting the collapse of their marriage and the destruction of their relationship with their children. There are lives that are undone by a single word or email.

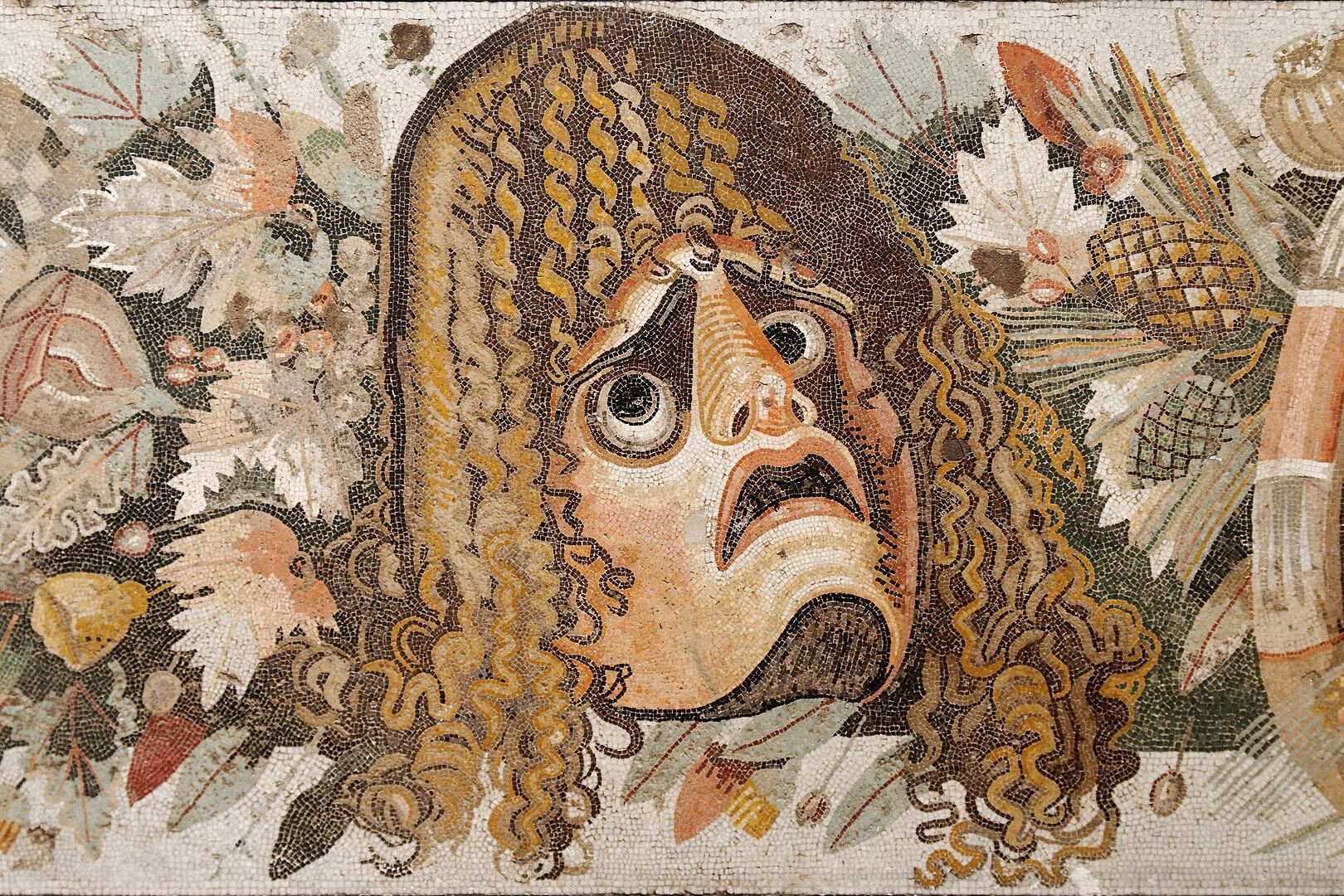

What defines tragedy is the disproportion between offence and punishment. There may be some primary fault: a lapse of reason, a degree of selfishness, an instance of lust or greed. But the toll is appalling and mesmerising in its scale and reach. It was the Ancient Greeks who first and best identified this possibility, named it tragic and gave rise to a tradition of writing plays in which one could at close quarters follow the disintegration of someone’s life from a relatively minor error to disaster, shame and death.

In the works of the great Greek tragedians – Aeschylus, Euripides, Sophocles – we observe intelligent, well-disposed characters who make errors of the sort we are all guilty of but, through the spiteful machinations of fate, have to pay an exceptional price for them. In Euripides’ Medea, Jason, an adventurer and an ambitious politician, grows bored of his wife, Medea. It is understandable enough: they have two children, the marriage has been lengthy, long relationships can be stifling. Jason finds himself falling in love with the beautiful and younger Glauce, daughter of King Creon; it happens all the time. What Jason does not foresee is Medea’s response: so incensed is she by the betrayal, so fragile is her mind, that she exacts revenge in the only way she knows will truly destroy Jason: by ending the lives of their children.

Tragedy is sadly not limited to legendary examples on the stage that we can leave behind after a few hours. The tragic dimension follows us deep into our own lives. We may try to push the possibility far out of consciousness. The media – through which we learn so much about the errors and crimes of our fellow humans – prefers to keep things simple. It regales us with a stream of one-dimensional villains: greedy capitalists, faithless spouses, sexual perverts. It tries to reassure us that harm only comes to the obviously wicked.

We want so badly to believe in such an assurance, but the reality is a good deal more nuanced – and lamentable. When we examine cases from close up, the apparently one-dimensionally evil business person we read about in a headline had no wish to destroy their whole company and ruin the livelihoods of thousands. The unfaithful spouse was carried away by momentary desire: the marriage had been barren for a long time, but they weren’t trying to drive anyone mad. The so-called pervert was beset by compulsions they regretted the moment they were exhausted. And all the while, these figures maintained sides that were generous, sweet-natured, intelligent and gifted. At the height of their fortunes we would have been proud to know them. And, needless to say, when they were little, they were filled with promise and had gleeful eyes and adorable smiles.

People emphatically do not get what they deserve. We are often short-sighted, selfish, greedy and cruel, but the intensity with which we have to suffer for some of our transgressions observes no reasonable limits. In the early hours, the world’s bedrooms are filled with people who both berate themselves for their mistakes and know that the record can never be expunged: the dead cannot be reborn, the relationship cannot be repaired, and there will be no other option but to suffer every day of what remains of a doomed life.

We need hearts of stone or simply uncurious minds not to be moved. We would be advised to show some form of loving response for an obvious and self-founded reason: because tragedy is likely to make an appearance in our own lives before too long. There is almost certainly already something that we have done – some oversight we are guilty of, some piece of malice we have perpetrated – that may set in motion a chain of events that could one day result in the destruction of everything we hold dear.

No one has guaranteed us protection from the unequal distribution of punishments; we are the playthings of the Gods, and the Greeks did their best to warn us on this score. There can be no reason to continue to cling to naive models of justice. We have no option but to pity every so-called ‘sinner’; we must battle our tragic fates with love.