Self-Knowledge • Emotional Skills

The Sorrows of Work

I. Introduction

There is no more common emotion to feel around work than that we have failed. We have failed because we have made less money than we’d hoped, because we have been sidelined in our organisation, because many of our acquaintances have triumphed, because our schemes have remained on the drawing-board, because we have been constantly anxious and because we have been, for long stretches, really very bored.

We tend to meet our sorrows personally. We believe our failures are tightly bound up with our own character and choices. But the suggestion here is that the single greatest cause of our professional failure lies in an area that self-aware, moderate and modest people are instinctively loathe to blame: the system we live within. Whatever our natural hesitancy, it seems we deserve to recast at least some of the explanations for our woes away from intimate experience towards large-scale historical and economic forces. Though on a daily basis, we are enmeshed in problems (inadequacies, desires, panics) that feel like they must be our responsibility alone, the real causes may in truth lie far beyond ourselves in the greater, grander currents of history: in the way our industries are structured, our values are determined and our assumptions generated. Capitalism has been, for a long time now, a confirmedly tricky system in which to retain equilibrium, make peace with ourselves, find fulfilment in our work – and cope. It’s not quite our fault if – rather too often – we feel like losers.

This isn’t to make a special dig at capitalism, or to suggest that there may be easier alternatives at hand. Every economy that has ever existed has been bound up with multiple sorrows. Organising an equitable system of incentives, rewards and goals is as yet beyond us. We should be allowed to level criticisms, not in the name of arguing for an alternative utopia, but in order to depersonalise our sense of failure.

Work disappoints us not by coincidence, but by necessity for at least eight central reasons: because the scale of industry robs us of a sense of meaning; because the demand for specialisation limits our potential, because the concentration of capital squeezes out personal initiative, because the extent of consumer choice forces us to commercialise our work beyond what feels tolerable, because competition generates a state of perpetual anxiety, because the requirements of collaboration madden us, because our high aspirations embitter us and because the notion that the world is meritocratic imposes a crushing burden of responsibility on us for our defeats.

Understanding the sorrows of work will not magically remove them, but it will at least spare us the burden of feeling that we must be uniquely stupid and clumsy for suffering them.

II. Specialisation

One of the great sorrows of work stems from a sense that only a small portion of our talents has been taken up and engaged by the job we do every day. We are likely to be so much more than the work we are employed for ever allows us to be. The title on our business card is only one of thousands of titles we theoretically possess.

In his ‘Song of Myself’, published in 1855, the American poet Walt Whitman gave our multiplicity memorable expression: ‘I am large, I contain multitudes’ – by which he meant that there are always so many interesting, attractive and viable versions of oneself, so many good ways one could potentially live and work, and yet very few of these can ever get properly played out and become real in the course of the single life we have. No wonder if we’re quietly and painfully constantly conscious of our unfulfilled destinies – and at times recognise with a legitimate sense of agony that we really could well have been something and someone else.

The big economic reason why we can’t explore our potential as we might is that it is hugely more productive for us not to do so. In The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, the Scottish economist and philosopher Adam Smith first explained how what he termed the ‘division of labour’ was at the heart of the increased productivity of capitalism. Smith zeroed in on the dazzling efficiency that could be achieved in pin manufacturing, if everyone focused on one narrow task (and stopped, as it were, exploring their Whitman-esque ‘multitudes’):

One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving, the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on is a peculiar business, to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper; and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations, all performed by distinct hands. I have seen a small manufactory where they could make upwards of forty-eight thousand pins in a day. But if they had all wrought separately and independently, and without any of them having been educated to this peculiar business, they could have made perhaps not one pin in a day.

Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, Book 1, Chapter 1 Of the Division of Labour (1776)

Adam Smith was astonishingly prescient. Doing one job, preferably for most of one’s life, makes perfect economic sense. It is a tribute to the world Smith foresaw – and helped to bring into being – that we have all ended up doing such specific jobs, and that we have titles like Senior Packaging & Branding Designer, Intake and Triage Clinician, Research Centre Manager, Risk and Internal Audit Controller and Transport Policy Consultant. We have become tiny, relatively wealthy cogs in giant efficient machines. And yet, in our quiet moments, we reverberate with private longings to give our multitudinous selves expression.

One of Adam Smith’s most intelligent and penetrating readers was the German economist Karl Marx. Marx agreed entirely with Smith’s analysis; specialisation had indeed transformed the world and possessed a revolutionary power to enrich individuals and nations. But where he differed from Smith was in his assessment of how desirable this development might be. We would certainly make ourselves wealthier by specialising, but we would also – as Marx pointed out with passion – dull our lives and cauterize our talents. In describing his utopian Communist society, Marx placed enormous emphasis on the idea of everyone having many different jobs. There were to be no specialists here. In a pointed dig at Smith, Marx wrote:

In communist society… nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes… thus it is possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, to fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner…without ever becoming a hunter, fisherman, shepherd or critic.

– Karl Marx, The German Ideology (1846)

Some of the reason why the job we do (and the jobs we don’t get to do) matter so much is that our occupations decisively shape who we are. How exactly our characters are marked by work is often hard for us to notice, our outlooks just feel natural to us, but we can observe the identify-defining nature of work well enough in the presence of practitioners from different fields. The primary school teacher treats even the middle-aged a little as if they were in need of careful shepherding; the psychoanalyst has a studied way of listening and seeming not to judge while exuding a pensive, reflexive air; the politician lapses into speeches at intimate dinner parties. Every occupation weakens or reinforces aspects of our nature. There are jobs that keep us constantly tethered to the immediate moment (A+E nurse, news editor); others that train our attention on the outlying fringes of the time-horizon (futurist, urban planner, reforester). Certain jobs daily sharpen our suspicions of our fellow humans, suggesting that the real agenda must always be far from what is overtly being said (journalist, antique dealer), other sorts intersect with people at the candid, intimate moments of their lives (anaesthetist, hairdresser, funeral director). In some jobs, it is clear what you have to do to move forward and how promotion occurs (civil servant, lawyer, surgeon), a dynamic that lends calm and steadiness to the soul, and diminishes tendencies to plot and manoeuvre; while in other jobs (television producer, politician), the rules are muddied and seem bound up with accidents of friendship and fortuitous alliances, inspiring tendencies to anxiety, distrust and shiftiness.

The psychology inculcated by work doesn’t neatly stay at work; it colours the whole of who we end up being. We start to behave across our whole lives like the people work has required us to be. Along the way, this narrows character. When certain ways of thinking become called for daily, others will start to feel peculiar or threatening. By giving a large part of one’s life over to a specific occupation, one necessarily has to perform an injustice to other areas of latent potential. Whatever enlargements it offers our personalities, work also possesses a powerful capacity to trammel our spirits.

We can offer ourselves the poignant autobiographical question of what sort of people we might have been had we had the opportunity to do something else. There will be parts of us we have had to kill (perhaps rather brutally) or that lie in shadow, twitching occasionally on Sunday afternoons. Contained within other career paths are other plausible versions of ourselves – which, when we dare to contemplate them, reveal important, but undeveloped or sacrificed, elements of our characters.

We are meant to be monogamous about our work, and yet truly have talents for many more jobs than we will ever have the opportunity to explore. We can understand the origins of our restlessness when we look back at our childhoods. As children, in a single Saturday morning, we might put on an extra jumper and imagine being an arctic explorer, then have brief stints as an architect making a Lego house, a rock star making up an anthem about cornflakes and an inventor working out how to speed up colouring in by gluing four felt-tip pens together; we’d put in a few minutes as a member of an emergency rescue team then we’d try out being a pilot brilliantly landing a cargo plane on the rug in the corridor; we’d perform a life-saving operation on a knitted rabbit and finally we’d find employment as a sous-chef helping make a ham and cheese sandwich for lunch. Each one of these ‘games’ might have been the beginning of a career. And yet we had to settle on only a single option, done repeatedly over 50 years.

Compared to the play of childhood, we’re leading fatally restricted lives. There is no easy cure. As Adam Smith argued, the causes don’t lie in some personal error we’re making. It’s a limitation forced upon us by the greater logic of a productive, competitive market economy. But we can allow ourselves to mourn that there will always be large aspects of our character that won’t be satisfied. We’re not being silly or ungrateful. We’re simply registering the clash between the demands of the employment market and the free, wide ranging potential of every human life. There’s a touch of sadness to this insight. But it is also a reminder that this sense of unfulfilment will accompany us in whatever job we choose: we shouldn’t attempt to overcome it by switching jobs. No one job can ever be enough.

There’s a parallel here – as so often – between our experience around work and what happens in relationships. There’s no doubt that we could (without any blame attaching to a current partner) have great relationships with dozens, maybe hundreds of different people. They would bring to the fore different sides of our personality, please us (and upset us) in different ways and introduce us to new excitements. Yet, as with work, specialisation brings advantages: it means we can focus, bring up children in stable environments, and learn the disciplines of compromise. In love and work, life requires us to be specialists even though we are by nature equally suited for wide-ranging exploration. And so we will necessarily carry about within us, in embryonic form, many alluring versions of ourselves which will never be given the proper chance to live. It’s a sombre thought but a consoling one too. Our suffering is painful but it has a curious dignity to it, because it does not uniquely affect us as individuals. It applies as much to the CEO as to the intern, to the artist as much as to the accountant. Everyone could have found so many versions of happiness that will elude them. In suffering in this way, we are participating in the common human lot. We may with a certain melancholic pride remove the job search engine from our bookmarks and cancel our subscription to a dating site in due recognition of the fact that – whatever we do – parts of our potential will have to go undeveloped and have to die without ever having had the chance to come to full maturity – for the sake of the benefits of focus and specialisation.

III. Standardisation

The sorrows of work are not limited to the likelihood that we will somewhat unwillingly be tied to a single field throughout our careers; even worse, our chosen field may itself turn out to be boring. We are liable to think that this fall into a tedious role must be our fault, a sign of our exceptional ineptness, but looked at dispassionately, boring jobs are in fact an inherent and quasi-unavoidable part of the modern economy.

When we speak of the opposite sort of a job, an interesting job, we tend to refer to work that allows for a high degree of autonomy, personal initiative and (without anything artistic being meant by the word) creativity. In an interesting job, we won’t simply be following orders, we will have latitude about what path we select to meet an objective or what we think the right solution to a problem might be. A good job, defined like this, is one that allows for a good measure of personalisation: who we are has an opportunity to be directly imprinted in the work we produce. We end up able to see the best parts of our personalities in the objects or services we generate.

A lot of the writing about the nature of work produced in Europe and the United States in the 19th century can be read as an attempt to understand how personalisation disappeared from the labour market (even as wages rose). The English art critic and social reformer John Ruskin proposed that the Medieval building industry had once been marked by a high degree of personalisation, evident in the way that craftsmen carved gargoyles – grotesque animal or human faces – in distinctive shapes high up on cathedral roofs. The stone masons might have had to work to a pretty fixed overall design and their toil was not always easy, but the gargoyles symbolised a fundamental freedom to place one’s stamp on one’s work. Ruskin also added more ruefully that the new housing developments of the industrial age were allowing no such freedom or individualism to flourish in the workforce.

Ruskin’s most devoted disciple, the poet and designer William Morris extended the range of this idea of personalisation in a discussion of the making of furniture, his own area of expertise. Morris argued that the traditional way of making chairs and tables allowed artisans to see parts of themselves reflected in the character of the things they were making. Every chair made by hand was as distinctive as its creator. In the pre-industrial age, thousands of people had been actively engaged in designing chairs across the land and every worker had been able to develop their own slightly nuanced ideas about what a nice chair should be like.

William Morris, Sussex chair, 1865

But an inevitable part of capitalism is a process of concentration and standardisation. There is a tendency for money, expertise, marketing clout and sophisticated distribution systems to be pooled together by a few big players, who outcompete and crush rivals and so achieve a daunting position in the market place. Barriers to entry rise exponentially. A well-financed operation can cut costs, assiduously research the preferences of consumers, marshall the best technology and provide goods that can be of huge appeal to consumers at the best possible price. As a result, the artisanal mode of production cannot possibly compete, as Morris himself discovered when the traditional workshop that he established to make chairs for the Victorian middle classes was forced into receivership after a price war.

Today, there are – of course – still a few furniture designers around, some of them very well known, but this cannot disguise that what we call ‘design’ is a hugely unusual, niche field employing only a minuscule number of actors. The majority of those involved in the making and selling of furniture will have no opportunity whatsoever to put their own character into the objects they are dealing with. They belong instead to a highly efficient army of labour that aims for rigorously anonymous execution.

Without intending to be mean-spirited or inherently hostile to the pleasures of work, capitalism has radically reduced the number of jobs which retain any component of personalisation in them.

For example, the Eames Chair, designed by Charles and Ray Eames, went into production in 1956. It is a highly distinctive creation that deeply reflects the ideals and outlook of the couple who designed it. If they had been artisans, operating their own small workshop, they would perhaps have sold a few dozen such chairs to their local customers in their lifetime. Instead, because they worked under capitalism for Herman Miller – a huge commercial office and home furniture manufacturing corporation – many hundreds of thousands of units have been sold over decades down to this day. A side effect of this triumph has been that the demand for well-designed, interesting chairs has been substantially cornered. Anyone wanting to make an office chair nowadays has to face the fact that it is already possible to buy a very nice example, designed by two geniuses and available for rapid delivery by a global company at a competitive price down a highly efficient network of local branches.

We are familiar with the idea that the wealth of the world is being ever more tightly concentrated in the hands of a relatively small number of people – the infamous 1%. But capitalism doesn’t only concentrate money. There’s a more poignant, less familiar, fact that it’s only a small number of people – a sometimes overlapping, but often different 1% – who can have interesting, that is ‘personalised’, work.

It’s telling that we are, at the very same time, obsessed with the romance of individual genius. Our society has developed a near fetishistic interest in stories of the exploits of brilliant startups, colourful fashion gurus and idiosyncratic film-makers and artists, characters who flamboyantly mould parts of the world in their own image and put their individual stamp on the things they do and make. We might like to think we’re turning to them for inspiration. But it may be more the case that we are using them to compensate us for a painful gap in our own lives. The stories of successful personalisation have come to the fore just when the practical opportunities for personalised work have diminished – just as it was in the 19th century, during mass migration to cities, that novels about rural life achieved unprecedented popularity among newly urban audiences. We may, through our addiction to stories of lone creative geniuses, be trying to draw sustenance from qualities that are in woefully short supply in our own day-to-day working lives.

The prevalence of stories of individual creativity feed the illusion that personalised work is more normal than it really is. The many interviews and profiles mask the fact that – for almost all of us – it will prove almost impossible to compete against the great forces of standardisation. For this reason, far more than because of anything we may ourselves have done, most of us are highly likely to find a considerable portion of our work awkwardly tedious and dispiritingly free of any opportunities to carve our own gargoyles.

IV. Commercialisation

A complaint regularly aired around many careers is that, in order to succeed at them, there is nowadays no option but to ‘sell out’. It appears that we will inevitably face a choice – between authenticity and penury on the one hand, and idiocy and wealth on the other. We are familiar with the complaint in the arts, of course. But the same dilemma shows up when an interesting restaurant seems unable to make a profit; when a specialist bread company goes into receivership; when a garden supply firm focusing on rare native plants can’t get a foothold in the market; when a sincere news site can’t turn a profit and when an ethically-based investment firm is doomed to operating on a tiny scale in comparison with its less high-minded competitors.

Behind the complaint lies a very understandable but at the same very ambitious yearning: that our most passionately-held beliefs and enthusiasms should be relatively painlessly, simply by virtue of their merits, become high priorities for others. Our instincts lead us to suppose that what we’re convinced of should swiftly prove equally compelling to strangers. Young children are particularly prone to this touching assumption. They may, on meeting a new adult, enthusiastically suggest that they join them in playing a favourite game, perhaps brew something on the miniature kitchen stove or impersonate one of their dolls, which shows how hard it is for a child to grasp how alien its pleasures might actually be to another person. Children aren’t silly, they are just highly attuned to their own nature and spontaneously convinced that others may share it. They are, in a naive but representative way, illustrating an instinct that stays with us all of our lives: the supposition that others will and must be moved by what moves us, that their value systems are, or should be, like ours; and that what we love can automatically be what the world loves.

But the reality is often humiliatingly and enragingly different. A novel filled with subtle character analyses and which takes inventive risks with plot structure might sell only very modestly, while one that pits good against evil in a predictable way, relies on well-tried narrative tricks and arrives at an implausibly happy ending will dominate the bestseller lists. A high-street chain might do a fabulous trade in cut-price dark grey polyester-cotton socks, while a thoughtful, original brand involving striking colour combinations and material sourced in Peru will fail entirely to find a market.

It is tempting to arrive at a despairing conclusion: that the economy is inherently devoted to delivering a personal affront to the better aspects of human nature. The truth is a lot less vindictive, but the tendency for the market to overlook or at least remain cool in relation to our more sincere and earnest efforts is nevertheless real – and founded on a raft of identifiable and stubborn forces in economic and psychological life.

One of the most basic of these forces is choice. It is in the nature of a growing, successful economy always to expand the range of choices offered to a consumer – and thereby, always to minimise the a priori claims of any one product or service. We can track the characteristic features of this development in relation to media. In 1952, a BBC radio broadcast of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony attracted an audience of five million listeners: approximately 16% of the UK’s adult population. Today, such a broadcast would claim a fraction of these numbers. What explains the difference is not – as some cultural pessimists might claim – that the UK population has over a few generations become a great deal less sensitive to the emotive force of German Romantic music; the fundamental difference is that today’s audience has many more options. In 1952, there were very few competing sources of entertainment. People listened en masse to the classical end of BBC radio because there was nothing much else to do. A producer who worked in the corporation had a great deal more authority than today’s equivalent not on the basis of superior genius, but because it was preternaturally hard for his listeners to find viable alternatives. This, rather nicely, gave certain high-brow things more opportunity to be attended to; but it also meant that many substandard services and products could enjoy a far larger role than their intrinsic merit warranted.

We know from the study of certain natural habitats that in situations of abundant choice (the warm seas around the Seychelles for example), attention will naturally go towards members of the species who are able to appear colourful, variegated and theatrical.

Much the same holds true for companies amidst the din and buzz of the human marketplace. What is brusquely called ‘selling out’ typically refers to a series of moves no more and no less sinister than the elaborate signalling to which all living things must submit in their efforts to be noticed. Amidst plenty, products and services must throw their qualities into dramatic relief, puff out their virtues, sound more confident than they perhaps are and lodge themselves in the minds of their distracted audiences with unabashed insistence. It is understandable if those who are particularly committed to higher values may baulk at such demands, resentfully condemning the pitilessness of an unfeasibly vulgar system.

There is another reason why modern audiences are likely to sidestep opportunities for high-minded consumption: because they are so exhausted. Modern work demands a punishing amount from its participants. We typically return from our jobs, at the day’s close, in a state of severe depletion, frazzled, tired, bored, enervated, sad. In such a state, the products and services for which we will be in the mood will have to be of a very particular cast. We may well be too brutalised to care very much about the suffering of others, and think empathetically of unfortunates in faraway tea plantations or cotton fields. We may have endured too much tedium to stay patient with arguments that are intelligently reticent and studiously subtle. We may be too anxious to have the strength to explore the more sincere sections of our own minds. We may hate ourselves a bit too much to want to eat and drink only what is good for us. Our lives may be too lacking in meaning to concentrate only on what is meaningful. To counterbalance what has happened at work, we may instinctively gravitate towards what is excessively sweet, salty, distracting, easy, colourful, explosive, sexual and sentimental.

This collectively creates a vicious circle. What we consume ends up determining what we produce – and in turn, the quality of jobs that are on offer. So long as we only have the emotional resources to consume at the more narcotic and compromised end of the market, we’ll only be generating employment that is itself rather challenged in meaning and compromised in dignity – which will further increase our demand for lower-order goods and services. We seem hampered by our existing conditions of employment from properly developing the sort of temperaments that could strengthen the sincerity and seriousness of our appetites and so decisively expanding the range of meaningful and non-depleting jobs we could have access to.

The price we pay for a marketplace that refuses to support high-minded efforts isn’t just practical and economic, it is also at some level emotional. One of our greatest cravings is to be recognised and accepted for who we are. We long for careful, insightful appreciation of our characters and interests. This was, if things went tolerably well, a little like what happened to us in earliest childhood, when a kindly adult, through the quality of their love, spared us any requirement to impress, or as we might put it, to market ourselves. We did not, in those early years, need assiduously to ‘sell’ who we were: we did not have to smile in exaggerated ways, sound happier than we were, put on seductive accents or compress what we had to say in memorable jingles. We could take our time, hesitate, whisper, be a little elusive and complex and as serious as we needed to be – sure that another would be there to find, decode and accept us. Everything we learnt of love ran counter to the mechanisms of Commercialisation.

No wonder if we harbour within us a degree of instinctive revulsion against commercial strictures. The need not to sell ourselves aggressively was not just part an earlier, simpler point in the history of the world (as scholars rightly point out), it was – more poignantly – also a moment in each of our personal histories, to which we may, in our hearts, always at some level long to return.

V. Scale

One of the strangest aspects of work is that we don’t do it solely, and sometimes even principally, for money – which makes us vulnerable not just to poverty, but also to crises of a more psychological kind. We harbour a highly demanding ambition to find work that can provide us with an ingredient that can best be captured by the word ‘meaning.’ We hunger for this meaning quite as much as we crave status or enrichment. Meaningful work comprises any activity which impacts positively on another’s life, either by reducing suffering or increasing pleasure – a definition which can stretch to encompass everything from the life-saving interventions of the cardiac surgeon to the seductive efforts of a pastry chef or Anatolian rug-weaver.

In truth, the vast majority of jobs contribute in some way to the welfare of others. Only a very few are properly devoid of meaning, for example, a career devoted to making fake remedies for hair loss or cancer perhaps, or one encouraging those on low-incomes to gamble more. However, crucially, a great many are in the odd position of being meaningful while not in any way feeling meaningful.

The problem is rife in the modern age for a very particular reason: because of the changes in the scale and tempo of work ushered in by industrialisation. Most work now takes place within gigantic organisations that are engaged in a variety of large, complicated and slow-moving projects – and where it can therefore be hard to derive, on a daily basis, any tangible sense of having improved anyone else’s life. The customer and the end product are, in the gigantic structures of modernity, simply too far away in space and too distant in time. One can be unable easily to reassure oneself of one’s worth and purpose when one is only a single unit among a twenty thousand strong team on four continents pushing forward a project that might be ready at best in five years time.

There are sound reasons why the work-practices of large organisations proceed at a glacial pace. Product developments in aeronautics and banking, oil and pharmaceuticals cannot happen overnight. The time-frames are logical, but in terms of individual experience, they go directly against our natural, deeply embedded preference for a rapidly unfolding story.

The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle observed that a key requirement for a satisfying piece of theatre was that it should be over relatively quickly. There might be tensions and complications and unexpected changes of direction, but in a few hours and three acts, there should be a feeling of a genuine completion. It’s not just in the theatre that speed is attractive. The concentration of action also helps to explain the appeal of sport. In ninety minutes, a football match can take us from a perfect, neutral start to a precise result.

However, if football were like modern work in terms of scale and pace, one can imagine it unfolding on eighteen pitches with 22 balls and 1,800 players kicking around for thousands of days without any overview of the progress of the game. By the standards of our innate longings, our work unfolds in a very disordered, over-extended and confusing way.

Our labour feels meaningful not only when it is fast, but also when we get to witness the ways we are helping others; when we can leave the office, factory or shop with an impression of having fixed a problem in someone else’s life. This pleasure too is threatened by scale. In the massive organisations of modernity, we may be so distant from the end users of our products and services as to be unable to derive any real benefit from our constructive role in their lives. Spending days improving terms on contracts in the logistics industry truly will lead to a moment when a couple can contentedly enjoy some ginger biscuits together in front of the TV; optimising data management across different parts of an aerospace firm truly will – along with thousands of other coordinated efforts – contribute to the moment when a young family can bond together on a beach holiday. The connections are genuine, but they are so extended and convoluted as to feel dispiritingly flimsy and unreal in our minds.

It’s a tantalising paradox, and a kind of tragedy, that because of the unavoidable scale of modern work, we may both pass our lives helping other people – and yet, day-to-day, be burdened by a harrowing feeling of having made no difference whatsoever.

Part of the answer to our feelings of disconnection and disorientation lies in a discipline at the heart of culture: the art of storytelling. As the complexity and scale of organisations increase, so we need to learn how to arrange a disparate selection of events into a master narrative that can lend them coherence and thereby remind us of how we might fit into a meaningful whole. A company’s ‘story’ has a lot in common with a large, layered novel. One can imagine a company novel that would begin with a description of someone accessing a bank account in Salzburg. The next moment, we would be in a restaurant in the Wan Chai District of Hong Kong where a deal was being hammered out to transfer crates to Dubai. Then the focus would be on a meeting taking place in a basement in Whitehall, where regulations for consumer goods would be discussed between ministers and a set of civil servants. Then would come a section set in a call centre in Phoenix, closely followed by a scene in a nursery in Seattle. But rather than a hopeless confusion, the point would be to reveal how these apparently random incidents were in fact profoundly interconnected – pointing to a grand synthetic goal: perhaps the creation of a new IT system for an office in Munich or a project to increase the flow rate of a pump production line in southern Spain. Ideally, every large company would have storytellers on the payroll.

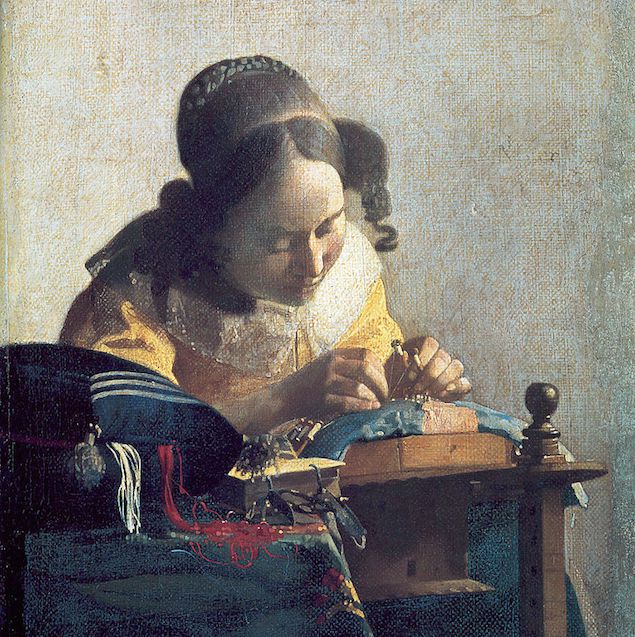

Jan Vermeer painted his famous milkmaid at work in 1657. Today, it is one of the most valuable paintings in the world. Some five million visitors come to see it at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam every year. However, despite the prestige, the moment being depicted could not be more ordinary.

It is only because of the skill and humanity of the artist that the activity unfolds as meaningful. Vermeer looks deep into his milkmaid’s work and finds in it an occupation that draws on humility, patience and a respect for procedure. Vermeer understands that a good life needs many things, and that milk (and cream and cheese and yoghurt) occupy a secure place on a very long list in which every element is – once we have learnt to appreciate it – indelibly connected up with others in a continuous chain of meaning. More than ever, we need the generosity of the artistic eye to render the purpose of work more visible to us as employees and to the world; so that the logic of our days will be less elusive and our disheartened moments less sapping and severe.

VI. Competition

At the heart of how all individuals function, there is a dream of security: security from humiliation, penury, dependence, arbitrary dismissal and uncertainty.

At the heart of how a modern capitalist economy functions, there is a dream of competitive advantage: one based on the intelligent exploitation of invested capital, on the effective deployment of technology, raw material and labour to reduce costs and improve quality and the triumph over competitors so as to maximise shareholder return.

At certain points, the two longings, those of individuals and those of capitalism, seem inherently aligned. At other points, it can seem as if our own well-being has grown entirely irrelevant to the economic machine we are enmeshed in. We generally don’t kick the machine. We’re far more inclined to blame ourselves. There is, after all, always enough evidence of people who thrive and succeed to suggest to us that the fault must lie with something we have done. But in our more politically engaged moments, we may dare to complain that the system really is not working ‘as it should’.

Ironically, at precisely such moments, it’s probably working very well indeed. It’s just that it was never intended to work in the way we would like: for our own well-being. Capitalism does not place the longings and aspirations of the labour force at the heart of its operations (the clue as to its essential concerns lie in its name). It wasn’t made to ensure that we had secure, good lives, plenty of time off and pleasant relationships with our families; it was made to maximise shareholder return. Labour has exactly the same status within capitalism as other production inputs, neither more nor less. Alongside rent, the price of fuel, plant, technology and taxes, labour (people) is just another cost. That it happens to be a ‘cost’ that cries, needs time off, has fragile nerves, sometimes catches the flu and in extremis commits suicide is – at most – a puzzling inconvenience. We shouldn’t believe that there is anything faulty about capitalism simply because we have minimal security of employment, very little time to see our families, a lot of stress and an uncertain future. These may belong to the very conditions that help the system to work very well. Our mistake, which has imposed a heavy internal burden on us, has been to confuse our own ambitions for happiness with the goals of the overall economy.

We have innocently viewed a range of anxieties and fears as incidental and solvable, when they are in fact basic necessities for the correct functioning of enterprise. The first, and largest of these is the Fear of Dismissal. A capitalist economy could not work well without it. It is a precondition of efficient business both that existing labour can be removed swiftly and cheaply and that there should always be a ready supply of cooperative replacements. Unemployment isn’t a tragedy for business; it contributes to a willing talent pool with low bargaining power.

Even the collapse and shuttering of whole firms isn’t – overall – to be lamented. Inefficient players who have failed to read market signals have to close and their capital has to be deployed elsewhere. There is nothing more unhealthy for capitalism than an economy in which venerable firms, some perhaps very long established and with thousands of loyal workers within them, can’t regularly and suddenly go bust.

The relationship we form to a company may last as long as a marriage and we may give it as much time and devotion as we would give to a partner. But this is a relationship that should, for capitalism to flourish, be close to abusive, because our ‘spouse’ must at any point be allowed, on the grounds that they could save themselves three percent a year, fire us bluntly and take up with a more cooperative and flexible rival in Vietnam or Bolivia.

We have taken care to construct a world where, in many areas, there is an extreme sensitivity to upset and distress. We have rigorous health and safety requirements to ensure people don’t fall off ladders or strain their backs moving heavy boxes. We make sure that words aren’t used to demean or prejudice minorities. Kindergartens present a moving picture of our care for the next generation.

And yet in the core area of our work, we operate in a system which is – from an emotional point of view – nothing short of inhuman. But through more sober economic lenses, it isn’t anything as alarming: it is merely admirably competitive.

A second fear that prevails is that of not having done enough. We lie awake at night worrying about certain tasks we failed to perform. We cannot stop thinking about what certain competitors may be up to. We panic about the upcoming financial results. We don’t sleep very well any more.

This too makes sense. It used to be far tougher on businesses. Regular breaks used to be mandated. Religion was responsible for many of them; it told people that they should down tools and honour something far more important than their work, like the majesty of the creator of the whole world. This glance upwards to the heavens relativised and calmed the workforce, it put things in perspective and lent a relieving sense that those packages in the warehouse could probably be sent next week after all. On a bad day, there might even be a sermon reminding people to treat workers like God’s children and to respect the holiness of every individual, however lowly.

In certain countries, labour got itself organised and demanded that everyone in the company had to be given decent conditions and the odd holiday, or else everyone would walk out on strike. There were angry marches and some insane demands to restrict who could be fired and when.

There were some very frustrating limits to technology as well. There was the post, but it took an age. One might have to wait two weeks for a letter and there might be little to do in that time other than check up on the garden, go for long walks, read three Russian novels and talk to the children. Travel for work took an equal eternity. One might be sent to Hamburg by the firm, which could mean four whole days, three of them at sea, some of them spent slowly eating kartoffelsalat and a schnitzel, chatting to fellow passengers and staring out from the ship’s window at the wheat fields near Neuharlingersiel.

It has been a miracle and an unbounded relief for capitalism that this painful age has at last passed. Religion now seldom gets in the way. Its irritating calming pieties have been replaced by far more alarming and motivating narratives drawn from social darwinism. The labour movement has been effectively pulverised by flattering ambitious workers into believing that they would gain far more by ditching their fellow indians and aiming to become chiefs themselves – and relabelling labour organisers enemies of progress. Technology has at last made it possible for the machine to be on at all hours and therefore for the line between leisure and work to be thankfully erased. We’ve been able to give people phones to make sure they are findable all the time and cleverly incentivised them to see these devices as toys for their benefit rather than glorified tracking bracelets for the firm. Travel has been hugely speeded up too, so that it is now possible to squeeze in meetings on a few continents in just a single day. There is blessedly little time left a worker can call their own.

The third and related fear is that we now have almost no time to invest in our personal lives. We constantly search for that elusive holy-grail quaintly termed by magazines ‘work-life balance’. But anyone who sincerely believes that such an equilibrium might be possible has not begun to understand the logic of capitalism.

Work and Love are our two greatest idols. But they are also locked in mortal combat. Work tends to win. The complaints against work from within love are notorious: that we are never around, that we are always tired, that we never give our partner our wholehearted attention, that we are obsessive about the office. It is helpful to recognise that modern ideas of love were invented in the late eighteenth century by artistic people who didn’t have real jobs and therefore made great play of the importance of spending constant time with a lover explaining and sharing feelings and recounting the movements of one’s heart. Unfortunately, combining Romanticism and Modern Capitalism together, as we are expected to do, is a near impossible task. The impressive philosophy of Romantic love – with its emphasis on intimacy and openness – sits very badly alongside the requirements of working routines that fill our heads with complex demands, keep us away from home for long stretches and render us insecure about our positions in a competitive environment.

According to the Romantic ideal, a lover can be kind and good only when they readily communicate their feelings. But the level of openness this assumes is wholly at odds with the realities of modern work. After a tricky day (or week), one’s mind is likely to be numb with worries and duties. We may not feel like doing much besides sitting in silence, staring at the kitchen appliances, running through a series of dramas and crises. Such preoccupation is not pleasant to witness: it risks expressing itself in a range of not very endearing symptoms: grunting, sighing, brooding silence and a short-fused temper. The most innocuous sounding question about how the day might have gone can elicit a growl – then, if it is repeated, an explosion.

In the pre-Modern age, the basic character of most jobs was well understood by everyone. If you were a shepherd, a blacksmith, a miner or a housemaid, you were doing work that would have been familiar to everyone in the community over many generations. The advent of the factory system in the early 19th century brought new kinds of work – but often whole communities would be employed in roughly the same industries, so everyone would understand what it was like to glaze pottery (if you lived in Staffordshire) or operate a steam loom (if you lived around Manchester). Today’s jobs are weirder and more specialised. Explaining properly the reasons why one day was more enervating than another, why a particular project has become so stress-inducing or why relations with the Madrid office have broken down can require levels of forbearance we cannot muster – when one of us has spent the day advising on restructuring the billing system for the annuity collection fund of an insurance broker while the other has been attending to the data collection mechanism for the multi-platform design mainframe of a logistics company. When we do not properly explain, we risk coming across as closed, difficult and an enemy of true love, though we are usually no such thing: we are just tired and worried.

Another way in which modern work is at odds with the requirements of relationships has to do with domestic duties, the always fraught question of who should clean the bathroom or renew the household insurance (issues to which Romantics devoted scant attention). The modern ideology of work assigns the domestic sphere a low status. Work around the house isn’t paid, which means it can’t be important, and it is in any case associated, historically, with socially subordinate positions, like those of the scullery maid, the footman and the gardener. As a result we tend not to take household management seriously. We admire people who can drive fast, but not those who can make a bed perfectly at high-speed. In modernity, unpaid work lacks all prestige. However, we cannot escape the domestic either. We live at a moment when pretty much everyone is involved (even if only a little) in housework. Having servants is an extreme luxury – even though for most periods of history, it was the norm for large sections of society to rely on help from others. In 1850 in Great Britain, for example, families with an income of GBP 300 a year (the basic income of any managerial job) would typically have two live-in servants. A clerk on half that (GBP 150 a year) would usually employ a full-time maid. Even just renting a room almost always involved access to a shared servant. But it has now become, in the most dynamic economies, prohibitively expensive to employ a fellow citizen to live in your house and make you cups of tea, dust the mantlepiece and clean the bath taps. We are left to squabble among ourselves about who will empty the bins. The technological developments of the 1950s and 1960s – vacuum cleaners, dishwashers, tumble driers etc. – certainly made domestic work a great deal less cumbersome, but they didn’t bring the chores to an end. We are still in the position of waiting for the long-promised robotic servants that finally will take domestic chores out of our hands entirely. They will become standard – eventually. They are sure to be cheap and common by 2050. Future social historians will note that there will have been a gap, running from around 1950 to 2050, in which domestic work was neither the province of servants nor of robots – but lay in the hands of almost everyone in the developed economies. A century is nothing in the big sweep of history. It’s just challenging that our lives have unfolded within it exactly.

After the taps and the dishes, and with equal challenges attached, come the children. Historically, it is very odd for business people – or indeed anyone with an executive role – to spend much of their day attending to the needs of their own children. People in the past weren’t heartless, they just didn’t think that it was particularly good for children to spend a lot of time with their parents. There was a prevailing fear of ‘spoiling’ one’s offspring by overt displays of affection and a shyness about spending too long in the nursery. It wasn’t until the early 1950s, first in the United States, then gradually across the rest of the developed world, that a new philosophy came to pass.

A number of researchers in the area of child development – especially the psychoanalyst, John Bowlby – stressed the importance for children of maintaining continuous and close relationships with their parents throughout their early years. Bowlby demonstrated the critical value of a warm, reassuring parental figure for the good development of every child. Playing on the carpet, bouncing balls, laughing over teddy’s antics, were, for Bowlby, no idle fun, these could be matters of psychological life or death for the child: “All the cuddling and playing, the intimacies of suckling by which a child learns the comfort of his mother’s body, the rituals of washing and dressing by which through her pride and tenderness towards his little limbs he learns the value of his own…all these are his spiritual nourishment.” A child’s sound development hung on the possibility of reliable, constant parental connection. “It is as if maternal care were as necessary for the proper development of personality as vitamin D for the proper development of bones.”

Bowlby didn’t mean for this to happen, but his insights into the principles of child development opened up a new landscape of pain for modern parents. Not making it back in time for bed became not, as it had once been, a minor inconvenience, but a potential new catastrophe. A tender, anxious part of every parent was awakened – and would now ache whenever he or she sat in gridlocked traffic or waited for a take-off slot on the tarmac at Heathrow. At the prospect of a business trip, a parent in the post-Bowlby era would have inwardly to fret at all the bath-times they would miss and the number of stories they would not have the chance to read. These were not worries that would have occurred to a knight returning from the Crusades. In 1095 – when his son Baldwin was two – Count Robert of Flanders, headed overseas on the First Crusade to the Holy Land. He came back home in August 1099. By which time he had missed 1,460 successive bedtime stories.

Robert of Flanders: unfazed by the number of unread stories

But this didn’t make Robert feel guilty or sad, because in 11th-century Europe, being a very good father was not assessed in terms of quantity of contact. Yet, in the light of our improved understanding of the needs of the child, Robert was barbarous. Our best – and also most time-consuming – ideas about how to raise a child have arrived on the scene exactly when we’ve also discovered some crucial things about productivity, efficiency, the division of labour, transcontinental transport, 24-hour shift work and digital technology. Our best ideas about how to run an economy and our best ideas about how to raise families are squarely at odds.

Finding a comfortable, harmonious balance between the demands of work and the needs of children sounds like an obviously good idea – and we can always find a few people in the world who seem to achieve it with ease – just as there are people who are good at high-wire cycling. But it’s very unlikely that you will be among them. We end up getting frustrated and angry with ourselves (and our partners) for failing to attain what is, in reality, a highly elusive condition. One might – with similar levels of justice – berate oneself for not combining a job in the accounts department of a supermarket chain with giving piano recitals at the Gesellschaft der Musik Freunde in Vienna.

If there is consolation to be found, it lies in knowing enough history to realise that failure isn’t personal. It isn’t one’s own incompetence or lack of drive that has set one’s work and home life at loggerheads. We just happen to be living at a point in time when two big, opposed themes are powerfully at war, when we have demanding ideas about the needs of families and relationships and equally demanding ideas about work, efficiency, profit and competition. Both are founded on crucial insights; both aim to monopolise our lives. The essential drive of capitalism is to provide more appealing goods at lower prices. While this is attractive for the customer, it is rather hellish for the producer: which of course means pretty much everyone in some major portion of their lives. The more productive an economy, the more conditions of employment will be less secure, less serene and more agitated than one might ideally like. We deserve a high dose of sympathy for the situation we happen to find ourselves in.

VII. Collaboration

One of the most frightening aspects of working life is that we will, unless we are the beneficiaries of extreme good fortune, be required to have colleagues. The colleague is a creature who, endured over any length of time in situations of high stress and procedural complexity, presents one of the greatest threats to calm, composure and soundness of mind.

It is noteworthy that, in the nineteenth century, one specific working environment developed into a hugely popular subject for painters: the artist’s studio. Archetypal paintings of studios showed high-ceilinged rooms with large windows, views over neighbouring rooftops, sparse furniture, messy tables covered in tubes of paint and half finished masterpieces propped up against the walls. There was one additional factor that particularly enticed the collective imagination: there was no one in the studio apart from the artist. At exactly the time when more and more people were being gathered into ever larger offices and experiencing for the first time all the attendant compromises and constrictions, there grew a craving for paintings of an alternative utopia, a place of work consolingly free of the damnable presence of the colleague.

Georg Friedrich Kersting, Caspar David Friedrich in his Studio, 1819

We’ve ended up in offices not by bad luck, but by the unavoidable fact that the mighty tasks of modern capitalism simply cannot be undertaken on one’s own. It remains (sadly) impossible to run an airline or manage a bank solo.

The problem with colleagues begin with the fundamental yet hugely tricky challenges associated with trying to communicate the content of one’s mind to another person. When we are doing things by ourselves, the flow of information is immediate and friction-free. If we could listen in to our inner monologues, they would be made up of a baffling speedy series of assertions and jumbled words: ‘narr, yes. come on! Do it till then, after no more. Ah, nearly, nononono, back…. OK got it got it… NO. Yes. That’s fine. So.’

But when we collaborate, we must laboriously turn the stream of consciousness (which only we can follow) into unwieldy externally-comprehensible messages. We have to translate feelings into language, temper our wilder impulses, affix paragraphs to intuitions – all in order to generate prompts and suggestions that have a chance of being effective in the minds of other people.

By a horrid quirk of psychology, others simply can’t by instinct alone understand what we need and want – though it can seem as though surely they must. The realisation that other people are not like us and can’t guess what we want takes a long time to sink in – and the idea perhaps always remains a bit foreign and unjust. In their earliest days, babies simply don’t realise that their mothers are in fact separate beings – and so get very frustrated when these reluctant appendages don’t by magic obey their unstated wishes. Only after a long and very difficult process of development (if ever) can a child realise that a parent is truly a distinct individual – and that in order to make themselves understood by them, they will have to do more than grunt and imagine solutions in their heads. It can be the work of a lifetime, in which the office occupies a particularly painful passage, to gradually accept the impossibility of mutual mind reading.

If this were not bad enough, many colleagues are at high risk of not sharing our underlying vision of what should be done. They have contrary opinions, their own quirks, pet peeves and obsessive interests. To get our point across and assuage their resistance requires us to deploy a battery of diplomatic skills. At the very moment when – agitated and overwhelmed – we would ideally like simply to shout or bark, it turns out we have no option but to charm.

This is because the colleague is, on top of it all, extremely sensitive. They will – unless they are spoken to correctly – become offended, develop grudges, start to cry or report one to a superior.

The imperative to be pleasant at work is a novel one we are still getting used to. In the olden days, brusqueness used to be the norm: it was a good way to get people to turn a boat swiftly starboard, push coal trolleys faster, or increase the rate of production at the blast furnace in a steel mill. When most work was physical, management could be abrupt; workers could feel underappreciated or bullied and nevertheless be able to perform their required tasks to perfection. Emotional distress didn’t hold things up. One could still operate the brick-making machine at maximum speed, even if one hated the manager, or clean out the stables thoroughly even if one felt the foreman hadn’t enquired deeply enough into the nature of one’s weekend.

But nowadays, most jobs require a high degree of psychological well-being in order to be performed adequately. A wounding comment can destroy a person’s productivity for a whole day. Without ample respect, recognition and encouragement, huge sums of money will be wasted in silently resentful moods. If one has any concern for the bottom line, one has no alternative but to try to be a bit nice.

At the same time, the inability to speak frankly has its own enormous cost. A huge amount of valuable information that should make its way around a company is held back by the imperative not to cause offence. One holds one’s tongue because one is scared to upset juniors, to alienate colleagues and to ruin one’s relationships with superiors – and in the process, insights that might help an organisation to thrive stay locked in individual hearts.

Work relationships are no less tricky than romantic ones, but at least in the latter, we have a basic sense of security that enables one to speak one’s mind and make the necessary cathartic moves – to call them fuckwits and compress a range of ideas in the occasional expletive loaded outburst. The office environment misses out on the cleansing frankness seemingly possible only when two people know they will have the option of having sex together after the bust-up.

At the heart of our office agonies is the complaint that we seldom like our colleagues as people. In a better world, we would be unlikely ever to want to spend any time at all with such disturbing, and often unlikely, figures. We shouldn’t be surprised by our daily discomfort, given that these people were never picked out on the basis of psychological compatibility. We were formed into a unit because they had a range of technical and commercial competences necessary for a task – not because they were fun lunch companions or were graced with a pleasing manner. We are like the unfortunate bride in a power-marriage in the middle ages. A princess would be obliged to marry a certain prince because he owned an important lead mine or the archers in his country were especially proficient. It would have been nice if the two liked each other a bit as well, but the stakes would be too high for this to be a relevant factor. The success of the realm depended on such matters as access to raw materials and military strength, not on whether the partner had a maddening giggle or a daunting overbite.

There is yet another challenge posed by colleagues. Corporations and businesses are fundamentally hierarchical, with an ever smaller number of desirable, better rewarded places at the pinnacle. A naive outsider might imagine that career progression would be determined by clear, precise and public determinants of merit, probably of a technical or financial sort, akin to the straightforward nature of the sort of examination results we all grew up with. But the reality is that in many occupations, no verifiable measure of performance is available. Factors of success are too numerous, opaque and shifting. What therefore decides who is promoted is not talent per se, but success at a range of dark psychological arts best summed up by the term ‘politics’.

Political skill has woefully little in common with the reasons we were trained and hired to do our jobs in the first place. We may, as part of a good business education, have spent years studying the way to navigate a balance sheet, analyse competitors, negotiate contracts, and administer a logistics chain. But when we reach the office, we will be confronted by other, less familiar kinds of challenges: the person at the desk opposite us with the charming manner who enthusiastically agrees with whomever they’re speaking to, yet who harbours a range of toxic reservations and privately pursues their own undeclared agenda; the person who responds to polite criticism or well-meaning feedback with immediate hurt and fury; the person who pretends to be our friend but knows exactly how to take the credit for our best efforts.

In such situations, the most unlovely qualities may turn out to be the most necessary ones: the capacity to quietly accept glory for things that were not truly our doing; to distance ourselves from errors in which we were in fact implicated; to subtly foreground the failings of otherwise quite able colleagues; to turn cold at key moments towards emotionally vulnerable superiors; to flatter while not appearing to do so; to mould our views to suit the currently ascendant attitudes.

Such grey, underhand strategies are not easy to pick up and they may feel plainly impossible for us to practice if we pride ourselves on being straightforward, direct or even just somewhat ethical. Yet we can be certain that any high-minded refusal of duplicity will carry a heavy cost indeed.

Our problems with the collegial nature of work are compounded, as ever, by the implication that matters should in fact be rather straightforward. Our inevitable difficulties are aggravated by notions that offices are at heart really giant families, that colleagues can be friends, that honesty is rewarded and that talent will win out. Kindly sentimentality is in the end, just a disguised version of cruelty. It might be a lot simpler if, in dark moments, we could simply admit to what we know in our hearts: that it would obviously be a great deal better if we could be shot of the whole business of colleagues and spend our days, as we used to so well, comfortably on the floor in our room assembling cargo planes, city car parks and picnics for families of bears.

VIII. Equal Opportunity

The modern world was founded upon, and continues to be enthused by, the promise of equal opportunity – and infinite possibility – for all. For most of human history, there was more or less no social movement, everyone remained in the stratified social class into which he or she had been born. The serf could never be a Lord; the ordinary citizen could not hope to be the ruler; the blacksmith would never get to live in the castle. This was the cruel caste system which seemed as natural as the earth and the stars and against which almost no one dared to complain.

But, just around the time when Adam Smith was publishing the Wealth of Nations in Edinburgh, the old order started to crumble. Thomas Jefferson informed the world that he and his fellow American signatories now declared it a ‘self-evident’ truth that ‘all men are created equal’ and that all deserved a shot at every kind of happiness, a deeply revolutionary and humane idea which had been wholly unevident until the Declaration of American Independence – but which now went on to transform humanity’s sense of possibility.

This exquisite idea continues to reverberate in every individual history. Each of us grows up with a sense that a great deal could be possible. Adults listen respectfully when small children suggest they might opt to travel to the Space Station, run the country or play for a winning team. Such feats really aren’t wholly fanciful, particularly when considered through parental eyes. Similarly transformative journeys are everywhere to behold. It would be churlish to ignore that extraordinary destinies are in fact a regular feature of modern life.

The idea of equal opportunity evidently springs from the most generous side of our nature and has been responsible for inspiring the most indispensable achievements. But it has also, unwittingly and far more quietly, been the source of unending sorrow. It was the American psychologist William James who most succinctly put his finger on the anxiety created by societies which promise their inhabitants infinite opportunities for social transformation and career success. For James, satisfaction with ourselves does not require us to succeed in every area of endeavour. We are not always humiliated by failing at things, we are only humiliated if we first invested our pride and sense of worth in a given achievement, and then did not reach it. Our ambitions determine what we will interpret as a triumph and what must count as a failure. ‘With no attempt there can be no failure; with no failure no humiliation. So our self-esteem in this world depends entirely on what we back ourselves to be and do,’ wrote James, ‘it is determined by the ratio of our actualities to our supposed potentialities. Thus:

Self-esteem = Success

___________

Pretensions

The problem with the modern world is that it does not stop lending us extremely high expectations. We are constantly invited to dream. Today, you may be a little short of cash, low on prestige and bruised by rejection. But these are – so it’s insinuated – transient troubles. Hard work, a positive attitude and bright ideas have every chance of breaking the deadlocks in due course. It’s all a question of willpower. There are always some quite encouraging stories in circulation of those who have put in the effort: for example, the person who trailed around South America for five years not doing very much of anything, then came back home, straightened out his life and founded a business now worth more than many of the world’s poorer countries. To further drive home the lesson of how possible such feats could be, this heroic figure doesn’t have a suit of armour; he looks like he could be a maths teacher or the guy who picked you up at the airport. Modernity never ceases to emphasise that success could, somehow, one day be ours.

This seems kind, but can end up torturing us, for reasons that the great French observer of 19th-century American life, Alexis de Tocqueville, well understood. In his book Democracy in America published in 1835, de Tocqueville reported on the distinctive agonies of life in the United States, and by extension, in the modern world: ‘When all prerogatives of birth and fortune are abolished, when all professions are open to all and a man’s own energies may bring him to the top of any of them, an ambitious man may think it easy to launch on a great career and feel that he is called to no common destiny. But that is a delusion which experience quickly corrects… That is the reason for the strange melancholy often haunting inhabitants of democracies in the midst of abundance, and of that disgust with life sometimes gripping them in calm and easy circumstances.’ Familiar with the limitations of aristocratic societies, de Tocqueville had no wish to turn the clock back to the period before 1776 or 1789. He saw that ordinary Americans enjoyed a standard of living which the lower classes of Europe in medieval days could not have dreamt of. Nevertheless, he appreciated that these materially-deprived lower classes had once benefited from a mental calm which the inhabitants of democratic North America and Europe would now forever be denied: ‘When royal power supported by aristocracies governed the nations…society, despite all its wretchedness, enjoyed several types of happiness which are difficult to appreciate today…Having never conceived the possibility of a social state other than the one they knew, and never expecting to become equal to their leaders, the people accepted benefits from their hands and did not question their rights. They…felt neither repugnance nor degradation in submitting to their severities, which seemed inevitable ills sent by God….the serf considered his inferiority as an effect of the immutable order of nature… At that time one found inequality…in society, but men’s souls were not degraded thereby.’

We have been forced to pay a high price for our high expectations: the price of disappointment for everything that we wish to be but fail to become. The old world had been kind with its pessimism. It was everywhere made apparent that life was fundamentally, rather than incidentally, frustrating and that the wisest approach was to learn to practice, from an early age, a philosophy of resignation and renunciation. However skilfully one wielded the scythe or with whatever diligence one raked the fields, it was clear that one would never fundamentally change one’s lot. As Seneca, one of the best known and loved writers of the pre-modern West, understood: ‘What need is there to weep over parts of life? The whole of it calls for tears.’ Or as Chamfort, that embittered and impoverished French writer of genius, put it: ‘A man should swallow a toad every morning to be sure of not meeting with anything more revolting in the day ahead’. The pessimists were being sweet. They were attempting to free us from the burden of expectation. They could see that a vast unthinking cruelty lay discreetly coiled within the magnanimous assurance that everyone could discover satisfaction on this earth. They understood that when an exception is misrepresented as a rule, our individual misfortunes, instead of seeming to us quasi-inevitable aspects of life, will weigh down on us like particular curses. In denying the natural place reserved for longing and disaster in the human lot, modernity’s ideology of hope has denied us the possibility of collective consolation for our stillborn ambitions and our disappointed careers, and condemns us instead to solitary feelings of persecution for having failed to meet expectations which were only ever deluded to begin with.

In the modern age, it isn’t just that we suffer from what we ourselves don’t achieve, we’re also agonised by what we can see other people achieving. We end up at once crushed and envious. Envy is a curious emotion in that we don’t – as we might suppose – feel it simply in relation to everyone who has more than us. We envy those who have more than us to whom we feel equal. We would, nowadays, be unlikely to feel envious of a member of the British monarchy. Their world is too remote from our own, their accents too odd, their characters alien. So despite them having a great deal more than us, despite their palaces, carriages and art works, we can walk past their lives without a trace of envy. And yet when we hear of someone our age, with a slightly larger apartment than ours, a somewhat more dynamic career and an ability to send their children to a slightly better school, our envy may grow boundless and quasi-obsessive. It is the feeling of equality – and not just differences in wealth and achievement – that drives envy. The closer two people feel, the more equal they are in each other’s eyes, the more any divergence of success will have the power to dispirit and enrage them. And the problem with the modern world is that it constantly informs us that we are indeed all equal deep down – while nevertheless holding up for our torture examples of people who have secured uncommon degrees of fame and wealth for themselves.

In the old world, it would not have occurred to any ordinary person to envy an aristocrat or monarch. These exalted characters lived in separate realms and went to great lengths to show the rest of the world how different they were – and how inconceivable it was that one could ever get to be like them. Their clothes, habits and ways of life made it clear one should never assume they were normal in any way.

Louis XIV: not like you

Louis XIV of France liked to wander about in ermine cloaks and gold brocade coats. He carried a golden stick. He sometimes donned a suit of armour. It was extremely haughty and unfair, of course. But it did have one great advantage. You could not possibly believe that you, in all your profane ordinariness, would ever reach the summit. You couldn’t possibly envy the mighty, because envy only begins with the theoretical possibility that one might be rightfully owed what the envied person has already got. Modernity was, by contrast, founded on an apparently generous sense that everyone is, in fact, owed the same things. Not in terms of current possessions and status, but in terms of potential. And yet it then performed a particularly a challenging move: it made sure that in fact, we don’t end up all having the same things at all. It combined the sense of possibility with the reality of inequality.

Even worse, the danger of envy has been exponentially increased by our constant exposure to news of the successes of others. A media saturated age brings constant reminders of what some have achieved, and we have not. In the Middle Ages, if you lived in Bristol (which was then a busy but small sea port), you probably wouldn’t know much about what was happening in London, Paris or the royal courts of Spain. Un-urgent information would simply never circulate around the country, for example, news that the ladies at court like to gather their hair up in net bags on either side of their faces or that they like red gauntlets sewn with pearls in floral patterns.

Blanche of Lancaster – wife of Henry IV – was the best dressed woman in late 14th-century England. But she couldn’t be fashionable – because it just took too long for people to find out about what she was wearing.

The daughter of a well-to-do merchant in Bristol might take a great deal of interest in clothes, but she couldn’t compare herself with the grander ladies of London like Blanche – because she simply didn’t know what they were up to. And, in any case, Blanche hardly seemed to belong to the same species.

Then, in August 1770, the first edition of the Lady’s Magazine appeared.

Every month it carried detailed illustrations of what the most prestigious women were wearing, so that news about bonnets and high waists could circulate rapidly around the kingdom. It also reported on the social activities of the wealthy and esteemed in a tone that felt at once chatty and intimate, as though these grandees were really our friends. Thanks to the tone of the stories, Lady Bedford was no longer an abstract, unknown aristocrat as remote as a species from another planet. She was someone a few years younger than you, with a very pretty waist, blue-grey eyes and delicate fan from Venice, who had recently been to a party at the home of the Marquess of Dorchester, where they served herring pie and shoulder of mutton with thyme and the carriages were due after 1 a.m.

Anyone reading could at last compare their own clothes and social engagements with those of the rich and well-connected in London. And so they were provided with the opportunity to experience a rather novel emotion: the feeling of having been wretchedly left out by fashion, society – and the world. They could sit by the window in the small village of Finchingfield in Essex, watching dull grey clouds scudding across the horizon, and know for the first time that life truly was elsewhere. Up until then, you might have been left out, of course, but only by people who you knew and who lived around you. Perhaps your cousins didn’t take you blackberry-picking or the vicar didn’t ask you to dinner. The magazine, however, presented itself as a reliable agent for revealing where every lady in the land was spending time and what they were wearing – except you. In truth, The Lady’s Magazine was not the disembodied voice of the spirit of the age speaking with universal authority. It was a precarious publication concocted by a man called John Coote in an unprepossessing office in Watling Street, near St Paul’s in London. But magazines can have a habit of sounding like they are the source of ultimate truth, when you flick through them in a disconsolate mood in an armchair in your parent’s house in rural England. The new media of the 18th century set about teaching a broad cross-section of society about the incompleteness of their lives: a yeoman farmer could learn from The Spectator that he was a clodhopper; The Tatler encouraged local squires to recognise their conversation as provincial; The London Magazine reminded the merchants of York that they were spending their lives in rather the wrong city; and teenage girls understood from Town and Country Magazine that any prospective husband would be lacking a great many attributes compared to the paragons it had identified. Better roads, more efficient printing techniques, the use of special-coloured inks, a reliable road system and cheaper postage had conspired to open up new and unfamiliar possibilities for self-disgust.