Leisure • Art/Architecture

Agnes Martin

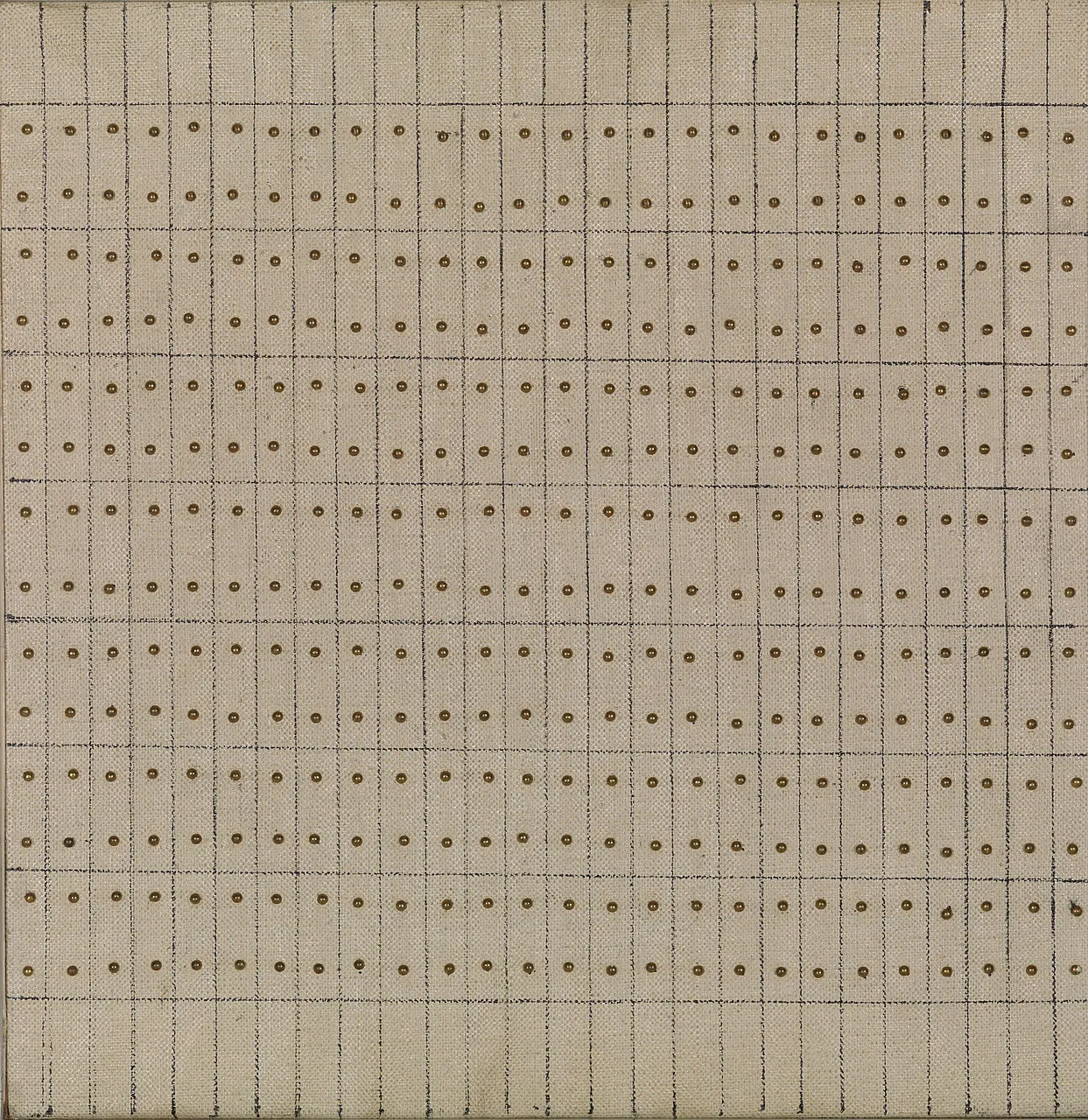

If there were to be a patron artist of melancholy, it might be the American abstract painter Agnes Martin. Over a long life (1912-2004), she produced hundreds of canvases, most of them 1.8 by 1.8 metres, showing not very much at all. From a distance, they can seem merely white or grey, though step nearer and you notice grid patterns hand drawn in pencil, beneath which run horizontal bands of colour, often a particular subtle shade of grey, green, blue or pink. There is an invitation to slough off the normal superficiality of life and bathe in the void of emptiness; the effect is soothing and moving too. For reasons to be explored, one might want to start crying. The works may appear simple but their effects are anything but: ‘Simplicity is never simple,’ she explained, having studied Zen Buddhism for many years and learnt that encounters with little can be frightening, because they remind us of our own ultimate nothingness, which we otherwise long to escape through noise and frantic and purposeless activity. ‘Simplicity is the hardest thing to achieve, from the standpoint of the East. I’m not sure the West even understands simplicity.’

In the little town of Taos, in the north-central region of New Mexico, where Martin spent her last years, one can visit the Agnes Martin Chapel, an octagonal room empty except for seven of her paintings and four steel cubes by her friend and fellow minimalist artist Donald Judd. We know how far we generally drift from what is important, how often we lose ourselves in meaningless chatter or attempts to assert our interests over those of others. The paintings bid us to throw aside our customary, relentless self-promotion. It is just us and the sound of our own heartbeat, the light coming in from an oculus above (across which a New Mexico cloud occasionally drifts), the patient work of thousands of hand-drawn grids repetitively punctuated by strips of the mildest hues of grey and pink – and the peace there would have been over the oceans when the earth was first created. Martin once remarked that her work was fundamentally about love, not the noisy exuberant Romantic variety, but the selfless patient sort a parent might feel for their sleeping newborn or a gardener might experience in relation to their seedlings.

The German early twentieth century art historian Wilhelm Worringer proposed that humanity had across history tended to make art of two kinds: abstract and realistic. On the one hand, there was an art of geometric non-concrete patterns (the abstraction one might see on a Navajo rug, a Persian mosque wall or a Peruvian basket), and on the other, there was art made up of depictions of people, things and places (lions in prehistoric caves, mountain landscapes, battle scenes). Worringer made an additional suggestion. What determines the sort of art a society is drawn to at a given moment is often the degree of chaos, difficulty and struggle to which it is subject. The more cacophonous a society, the more it tends to be attracted to the serenity and peace implied by the sober repetition of geometric patterns, just as quieter eras may seek out new vigour in bold images of mounted generals or waterfalls. We attempt to correct via art imbalances in our own emotional economy.

By implication, we shouldn’t suppose that Agnes Martin was as peaceful as the canvases she turned out. When still a young woman, she was diagnosed as paranoid schizophrenic and she suffered from repeated bouts of extreme depression. She would often hear voices in her head criticizing her and urging her to take her own life. It could be hell inside her mind. It is understandable that she might as an artist have felt compelled to produce some of the most serene works the world has ever known, that she gained boundless relief from spending hours – and overall decades – alone in a simple house on the edge of the New Mexico desert, listening to Bach and Beethoven, tracing grids on canvases and applying paint in colours that Zen Buddhism identifies with the renunciation of the ego and the alignment of the self with cosmic harmony.

If we are moved, if we are tempted to start crying, it’s not because our lives are themselves extremely serene. It’s because – like the artist herself – we have for far too long been familiar with mental perturbance, because we know what it means to have inner voices insisting on our worthlessness and how right one might be to die. Martin matters because she gives dignity to a longing for something infinitely more harmonious and loving than the world can generally offer. The canvases are like a map to a destination we have lost sight of and can’t get back to. They are our Ithaca. We might point to them and say that this is where we belong, this is the repository of everything we prize but have too fragile a hold on. The paintings lend us the courage to cut ourselves free from our unhealthy attachments, to say goodbye to concerns for status, to shun the pursuit of public esteem, to dismiss false friends who do us nothing but underhand harm, to accept the terror of disgrace, to reconcile ourselves to our own company and to pursue connections with just a very few honest souls who have known struggles and been rendered kind by them. The paintings are what we could be if we sat with our own feelings and let their range course through us, if we gave up using our clever minds to ward off sadness and stopped trying to make sense of every experience, if we made our peace with mystery and the encroaching darkness that will eventually subsume us.

Nowadays, by the typically perverse accidents of the art market, Agnes Martin’s paintings cost as much as airplanes. They can only generally be seen in bustling public museums. In a better world, we’d all be able to have a few. As it is, we can at least spend time with them in high quality online versions and printed reproductions. They are sad pictures, in the best of ways. They know of our troubles; they understand how much we long for tenderness yet how rough everything has been day to day, they want us to have the simplicity of little children and the hearts of old wise people who have stopped protesting and started to welcome experience. The titles that Martin gave her paintings indicate some of what she was getting at: Loving Love, Gratitude, Friendship and – best of all, I love the Whole World, which implies the sort of love one experiences not when everything has been hunky dory, but when one has after the longest time come through to the other side of agony.

Agnes Martin, I love the Whole World, 1993

We can follow the grids and be happy. There’s one rectangle after another, one dot after another, nothing more troubling than lines of grey and white, no more surprises and departures, nothing unforeseen or cruel, only Agnes’s careful pencil, riding along the little bumps that tremble beneath unprimed canvas. It’s like she’s guiding us step by step, as one might a small child or a very old person, from square to square, making the world more manageable again, reducing its strident, clattery riot to something we can ingest, she’s cutting up the food of life for us into very neat and precise squares. She knows how unsteady we have felt. Occasionally, after a lot of greys, she goes for a pink, as though to hell with reserve, why not surrender to sweetness and take a risk with innocence. She’s giving us a hug, she’s inviting us to come to the window and watch a new day with her through her frame.

To those who don’t see anything in her work, one hopes that life won’t teach its lessons too painfully. To everyone else, it will feel like a melancholy homecoming. One will know that someone else has understood, has been as ill, and has been as committed to hope, endurance and kindness.