Relationships • Mature Love

The Benefits of Insecurity in Love

We tend to assume that the best foundations for a good shared life for a couple lie in making an explicit commitment (probably in front of 200 guests and a large cake) to staying together for the very long-term. The more we are guaranteed that someone is going to stay with us pretty much indefinitely, the more we can mobilise our best sides and bring our virtues into play.

But at times, it might pay to consider an alternative and more paradoxical truth: that a healthy dose of insecurity, of wondering whether the other person truly is duty-bound to stay with us forever and vice versa, might in reality be the ingredient that helps us to be better people, to curtail our more self-indulgent sides and to conduct a more flourishing and valuable relationship. Rather than drowning in insecurity, might we not benefit – at points – from emphasising and embracing the fragility of our alliance? Rather than a solemn promise that this is forever, might the most romantic move (in the sense of the move most likely to enhance and sustain love) not be a gentle reminder that we could very well no longer be an item by next month?

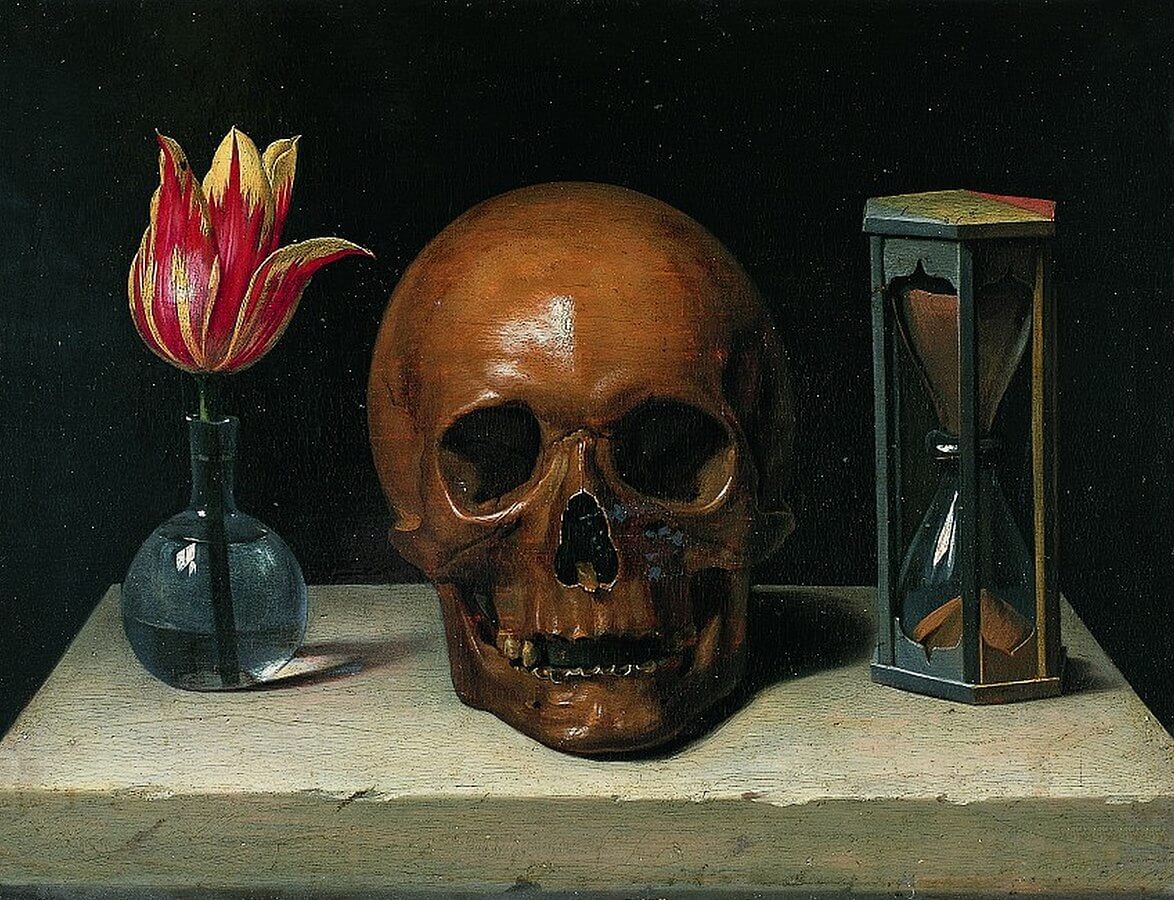

Insecurity sounds unromantic, but one of its major consequences is the possibility of appreciating why we remain together. So long as we believe we are irrevocably attached, there is no need to feel grateful for a partner’s positive sides or to notice their contributions to our welfare. All these are merely a given, part of the irredeemable fabric of our emotional reality. It tells us something of the importance of remembering endings that, for centuries, the most fitting piece of interior decoration for a prosperous person’s study was taken to be a skull: a real-life skull with ghoulish eye sockets and anguished looking rotten teeth, so that as merchants or politicians went about their business, they would never be far from a reminder that every second was of value.

We should have our own skulls around love. For much of our romantic lives, however much the intellectual idea is in place, the reality of love’s demise remains only in shadow. It’s not a concrete, powerful conviction that courses through us every hour. And though this allows us to bring a reassuring degree of innocence to our plans, it is also the breeding ground for the most profound emotional complacency. We may not experience ourselves as inured to our partners, but in the lackadaisical way we too often approach them, we are implicitly behaving as if the business of waking up every new day next to them had privately been guaranteed to us by an all-knowing god – rather than was a gift daily offered to us by a fellow option-rich mortal.

Another paradoxical-sounding result of good insecurity is that it reduces the dangers of bitterness and suppressed irritation. So long as we have no option but to stay, a lot of what we’re unhappy about may end up hidden, because our complaints have nowhere to go. We can lose the right to have our needs listened to and respected because both sides know that there is no alternative. Our threats have no ammunition in them, we can stamp our feet like impotent emperors. However, when the relationship is fruitfully insecure, we can confidently state our problems with how things are, both sides knowing that our words mean something. And, of course, they can in turn make their dissatisfactions plain to us with equal force. We’re importing into the depths of our relationships some of the qualities that naturally attended their fragile beginnings: the empathy, the care and the effort to be pleasant. In a state of constant insecurity, the important focus becomes on why it might be exciting or helpful or interesting to stay together; it turns the decision to remain in a couple into a loving, authentic choice rather than a prison to which no one has the key.

It may sound kind but we are doing another person, and ourselves, a proper disservice when we promise we will never leave them. There is nothing more likely to usher in the death of love than the whispered words: I will always be with you. We can appreciate the touching sentiment; but we should never let ourselves become trapped in its many asphyxiating consequences.

Insecurity is, along the way, also hugely sexually enticing. There is nothing more devastating to sexual self-confidence than our knowledge that we could never legitimately be of appeal to anyone but our partner – or that they have themselves grown invisible to the rest of humanity. We want what others want – which might include slipping our hand inside our momentarily intriguingly-distant partner’s top. It’s when our lover spots us flirting with an unknown person at a party or when we are forced to note how appealing they are to an audience of strangers that sex will once again be more than a chore. It’s not for nothing that the most intense sex that long-established couples ever have is right after a furious argument, that is, after a vivid encounter with the independence and fiery competence of someone they had for too long mistaken for furniture. Feeling jealous is simultaneously the most abhorrent emotion and the one most necessary to galvanize us back into erotic life.

To get the benefits of insecurity, leaving has to be a real possibility. Our readiness to quit can’t be uttered as a hollow threat blurted out when we are fed up or angry while both sides know that we would in reality be pressed to pack our own suitcase or operate our bank account. It has to be built upon a mature realisation that it would be inherently plausible for us to be on our own; that we could manage our own finances, construct a decent social life and do the grocery shopping.

If there are children involved, it is sometimes argued that that they need to know that we will never part in order to have the security to develop without anxiety. But this is – once more – a misreading of the benefits of eternal promises. Maintaining insecurity in a couple isn’t about trying not to be together; it’s about understanding the best preconditions for being so.

Therefore, one of the most constructive things we might do, in the pursuit of a more fulfilling relationship, is to look in an estate agent’s window and work out, realistically, how we could get an apartment for one. With a secure, positive sense of our own capacity for independence we would learn to see our relationship not as the union of two desperate, option-less people unable and too frightened to face life alone, but of two creative independent, sexually alluring individuals who could have an extremely interesting time apart but have chosen to take real pleasure in being with one another to enrich themselves and grow – at least for the time being…