Leisure • Eastern Philosophy

Buddha

The story of the Buddha’s life, like all of Buddhism, is a story about confronting suffering. He was born between the sixth and fourth century B.C., the son of a wealthy king in the Himalayan foothills of Nepal. It was prophesied that the young Buddha — then called Siddhartha Gautama — would either become the emperor of India or a very holy man. Since Siddhartha’s father desperately wanted him to be the former, he kept the child isolated in a palace with every imaginable luxury: jewels, servants, lotus ponds, even beautiful dancing women.

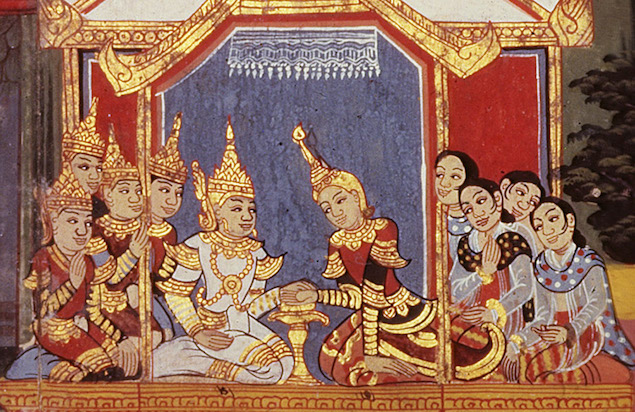

Young Prince Siddhartha with his bride and servants

For 29 years, Gautama lived in bliss, protected from even the smallest misfortunes of the outside word: “a white sunshade was held over me day and night to protect me from cold, heat, dust, dirt, and dew.” Then at the age of 30, he left the palace for short excursions. What he saw amazed him: first he met a sick man, then an aging man, and then a dying man. He was astounded to discover that these unfortunate people represented normal—indeed, inevitable—parts of the human condition that would one day touch him, too. Horrified and fascinated, Gautama made a fourth trip outside the palace walls—and encountered a holy man, who had learned to seek spiritual life in the midst of the vastness of human suffering. Determined to find the same enlightenment, Gautama left his sleeping wife and son and walked away from the palace for good.

A Chinese painting from the Tang Dynasty shows Buddha discovering illness and old age

Gautama tried to learn from other holy men. He almost starved himself to death by avoiding all physical comforts and pleasures, as they did. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it did not bring him solace from suffering. Then he thought of a moment when he was a small boy: sitting by the river he’d noticed that when the grass was cut, the insects and their eggs were trampled and destroyed. Seeing this, he’d felt compassion for the tiny insects.

Reflecting on his childhood compassion, Gautama felt a profound sense of peace. He ate, meditated under a fig tree, and finally reached the highest state of enlightenment: “nirvana,” which simply means “awakening”. He became the Buddha, “the awakened one”.

A second-century carving of the Buddha receiving enlightenment under a fig tree, surrounded by admiring members of creation

The Buddha awoke by recognising that all of creation, from distraught ants to dying human beings, is unified by suffering. Recognising this, the Buddha discovered how to best approach suffering. First, one shouldn’t bathe in luxury, nor abstain from food and comforts altogether. Instead, one ought to live in moderation (the Buddha called this “the middle way”). This allows for maximal concentration on cultivating compassion for others and seeking enlightenment. Next, the Buddha described a path to transcending suffering called “the four noble truths.”

The first noble truth is the realisation that first prompted the Buddha’s journey: that there is suffering and constant dissatisfaction in the world: “Life is difficult and brief and bound up with suffering.” The second is that this suffering is caused by our desires, and thus “attachment is the root of all suffering.” The third truth is that we can transcend suffering by removing or managing these desires. The Buddha thus made the remarkable claim that we must change our outlook, not our circumstances. We are unhappy not because we don’t have a raise or a lover or enough followers but because we are greedy, vain, and insecure. By re-orienting our mind we can grow to be content.

The fourth and final noble truth the Buddha uncovered is that we can learn to move beyond suffering through what he termed “the eightfold path.” The eightfold path involves a series of aspects of behaving “right” and wisely: right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. What strikes the western observer is the notion that wisdom is a habit, not merely an intellectual realisation. One must exercise one’s nobler impulses. Understanding is only part of becoming a better person.

Seeking these correct modes of behaviour and awareness, the Buddha taught that people could transcend much of their negative individualism—their pride, their anxiety, and the desires that made them so unhappy—and in turn they would gain compassion for all other living beings who suffered as they did. With the correct behaviour and what we now term a mindful attitude, people can invert negative emotions and states of mind, turning ignorance into wisdom, anger into compassion, and greed into generosity.

Art being invited to support philosophy: a beautifully carved eight-spoke wheel commonly used as a Buddhist symbol. The eight spokes represent the eightfold path

The Buddha travelled widely throughout northern India and southern Nepal, teaching meditation and ethical behaviour. He spoke very little about divinity or the afterlife. Instead, he regarded the state of living as the most sacred issue of all.

After the Buddha’s death, his followers collected his “sutras” (sermons or sayings) into scripture, and developed texts to guide followers in meditation, ethics, and mindful living. The monasteries that had developed during the Buddha’s lifetime grew and multiplied, throughout China and East Asia. For a time, Buddhism was particularly uncommon in India itself, and only a few quiet groups of yellow-clad monks and nuns roamed the countryside, meditating quietly in nature. But then, in the 3rd century B.C., an Indian king named Ashoka grew troubled by the wars he had fought and converted to Buddhism. He sent monks and nuns far and wide to spread the practice.

Buddhist spiritual tradition spread across Asia and eventually throughout the world. Buddha’s followers divided into two main schools: Theravada Buddhism, which colonised Southeast Asia, and Mahayana Buddhism which took hold in China and Northeast Asia. The two groups sometimes distrust each other’s scriptures and prefer their own, but they follow the same central principles passed down through over two millennia. Today, there are between a half and one and a half billion Buddhists following the Buddha’s teachings and seeking a more enlightened and compassionate state of mind.

Modern monks meditate under a fig tree near the place the Buddha first attained enlightenment

Intriguingly, the Buddha’s teachings are important regardless of our spiritual identification. Like the Buddha, we are all born into the world not realising how much suffering it contains, and unable to fully comprehend that misfortune, sickness, and death will come to us too. As we grow older, this reality often feels overwhelming, and we may seek to avoid it altogether. But the Buddha’s teachings remind us of the important of facing suffering directly. We must do our best to liberate ourselves from our own tyrannous desires, and recognise suffering as our common connection with others, spurring us to compassion and gentleness.