Work • Consumption & Need

The Entrepreneur and the Artist

The entrepreneur is one of the key figures of the modern economy, though what an entrepreneur does is perhaps not entirely properly understood.

There are certain conspicuous activities of entrepreneurship: raising capital, running factories, organizing supply chains or working out how to take existing products to new markets (how to increase sales of electric cars in Australia, for instance).

But then there’s a more private and primary first move behind entrepreneurial activity, which might be called sensitivity: in particular, sensitivity to pleasures and pains that others might overlook… or not take seriously enough or not fully focus on.

It can sound like an odd point. We don’t automatically associate entrepreneurs with being highly sensitive people. We’re more likely to associate sensitivity with non-commercial individuals like artists. Our point, though, is that entrepreneurs actually have this quality in common with artists. Collectively, our culture has understood the role of sensitivity around the arts, but not yet fully grasped its important role in entrepreneurship.

The Artist

There are two essential ways artists display sensitivity: to pleasure and to pains.

The Artist’s Sensitivity to Pleasure

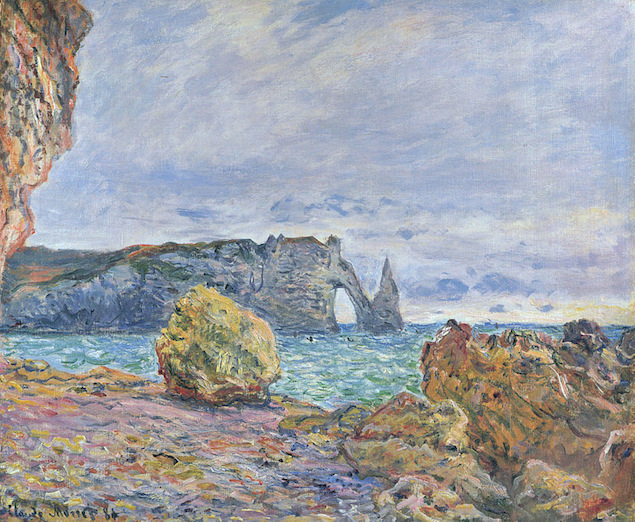

In the 1880s, the largely deserted, rugged coast of Normandy was visited by the impressionist painter Claude Monet. He was particularly attracted to the cliffs near the village of Etretat. Many local people and one or two rare visitors must occasionally have had the fleeting thought that it was a charming place as they drew up a fishing boat on the sand or collected the iodine rich kelp. The difference with Monet is that he took the pleasure of looking at the cliffs very seriously. He painted a series of works closely examining how beautiful the light was at different times of day and he studied the pattern of shadows on the rocks. For him, the cliffs were the source of an important pleasure and he painted them so as to get other people to share his enjoyment.

The Artist’s Sensitivity to Pain

In the early years of the 20th century, a dancer and choreographer called Isadora Duncan grew more and more frustrated by the pains of constrained Victorian clothing. Everyone else seemed to take it for granted that women and men should spend their days encased in highly formal and elaborate costumes, with corsets, buttoned arm-length gloves, stays and high collars. But instead of just suffering in the usual way, Isadora Duncan focused her attention on it and became determined to fix the problem. That’s why she decided to start dressing her dancing troupe in short, light, flowing tunics. Suddenly one could – for the first time in centuries on the stage – see bare legs. The history of 20th-century fashion owes an enormous debt to Duncan. It is she who liberated our bodies.

A decade later, the architect Mies Van der Rohe started to get fixated on the pains associated with visual chaos and squalor in cities and homes. He was frustrated by domestic architecture that was fussy, cluttered and complicated. Similar thoughts must have occasionally occurred to many people. But Mies van der Rohe held his annoyance very clearly in his mind and set out to find a solution. In 1927, he designed the Barcelona Pavilion which showed how these pains could be avoided in a simple and gracious way.

These were artistic insights. But they were later taken up by other more business-minded people and evolved eventually into major commercial enterprises, like the tourism industry of Normandy, the casual clothing business and the field of modernist property development.

The Grand Hotel, in nearby Cabourg, built in 1907

The Entrepreneur

Receptive antennae, highly attuned to pleasures and pains, are not the exclusive possession of people we call artists. An artist is not so much an individual who is necessarily more receptive than any other kind of person. What distinguishes an artist is that they use their sensitivity to make things like pictures, ballets or one-off designs for buildings.

But there’s another possible outcome, and that’s one where sensitivity is channelled directly into commerce. The pattern is less familiar, but it’s positive impact on our lives is potentially greater than the work of even the most celebrated artists.

Airbnb originated in a distinctive experience of pleasure that was taken very seriously by the co-founder and CEO Brian Chesky. He really liked having new people to stay on blow-up mattresses in his apartment; it was fun meeting them over breakfast; there was a nice atmosphere, because he was really helping them out. He was also taking very seriously the pain of not being able to find a place to stay when wanting to go to an industry conference.

In the hands of an artist this could have led to some impressive works of art. There might have been a fabulous installation around the theme of inflatable beds; or perhaps a specialist art book of moody photographs. These works would have sought to convey to others the surprisingly charming experience he had of having paying guests in his own home.

Founding a company grows out of exactly the same original insight. But it has a bigger ambition. Instead of just telling others about how nice this could be, the business directly enables other people to have the same satisfaction themselves. And it is then able to share this pleasure on a very large scale.

Artists traditionally have been very alive to their sensations: they’ve noted things that delighted them; they’ve noted constraints, discomforts, sorrows and frustrations. And they’ve made works of art to hold our attention more securely on these important but fleeting impressions. We need entrepreneurs to register their own pains and pleasures with equal devotion. For this task, the history of the arts offer an inexhaustible fund of inspiration for the entrepreneur.

To build a business many other familiar skills have to be brought in as well. But all the financial and managerial efforts are ultimately going into orbit around the original insight. Boiled down to its essence, business is the commodification of a moment of sensitivity.

Conclusion

We’re not simply noting that up to now there have been some impressive cases where businesses have emerged from the sensitivity of a few remarkable entrepreneurs. We’re highlighting a key ingredient of entrepreneurial activity. We’re imagining (and praising in advance) the entrepreneurs of the future, who will progressively investigate more and more of the pleasures and pains of existence – just as artists up to now have mapped the same terrain. So we should start to lessen the sense of distance between the activities of the two groups of people, who have often been seen as entirely different human types: both artist and entrepreneur build off the same crucial base of acute sensitivity taken very seriously and brought ambitiously to the attention of others.