Sociability • Friendship

The Friend Who Balances Us

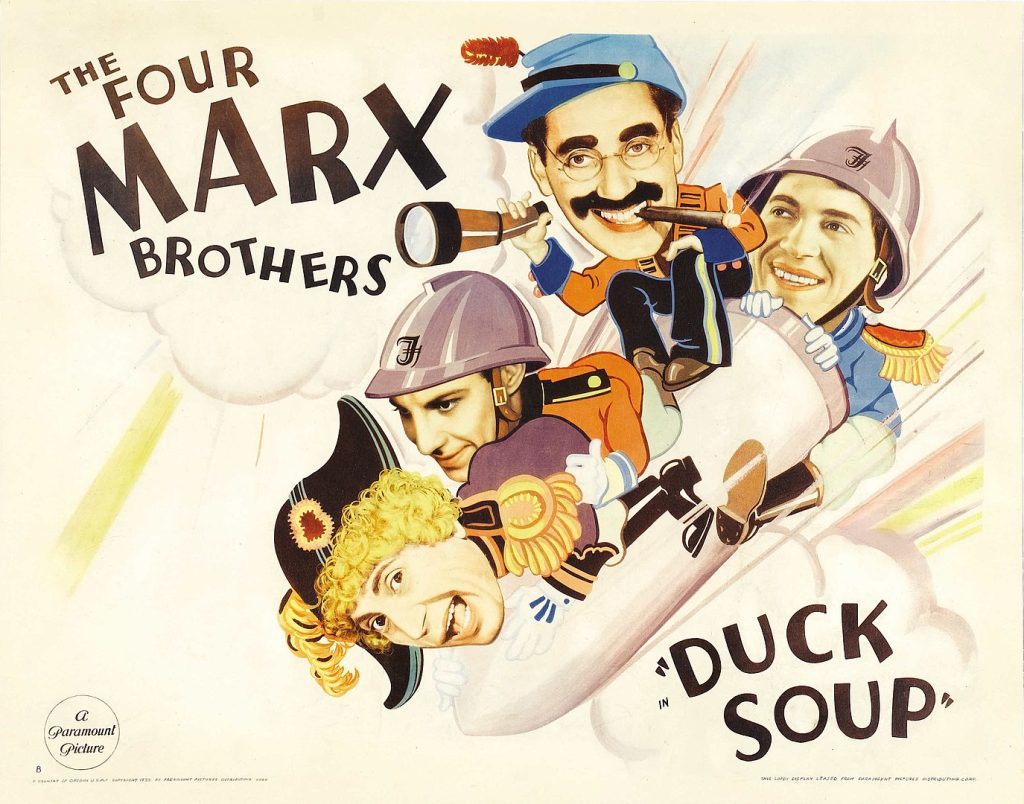

Amongst the less-expected of historical friendships is one that developed during the 1960s between two cultural figures who were almost crazily different: the cerebral poet T. S. Eliot and the anarchic comedian Groucho Marx.

In 1961, Eliot, who was obsessed by tradition, decorum and obscure references to Dante and was now in his seventies, wrote a fan letter to Marx – world famous for his irreverent, slapstick humour. It was a bid for friendship. Marx responded warmly and the two became important to one another in the few years before Eliot’s death.

This isn’t just a matter of dated celebrity gossip. It’s a moment when we can glimpse what we ourselves might be looking for in friendship. There’s a huge tendency to assume that friends are like one another; that we want and need to be around those who share our experiences and our outlook. But Eliot and Marx are charting a different approach. Philosophically, the question is: why might we want and need to be friends with those who aren’t like us at all? An answer lies in a submerged problem of every life: the extent to which we become one-sided and over-invest in a part of our nature at the expense of our true potential. We may seek in friendship to correct our imbalances of character; to locate in another the missing piece of ourselves.

Groucho (born in Manhattan in 1890) had, in his difficult, financially strained childhood, wished to become a doctor – that is to master the most socially respected body of knowledge he could imagine. In fact he had to leave school at the age of twelve to help support his family.

Tom (the ‘T’. in T. S.) was born into a distinguished and wealthy family, where high intellectual achievement was a central path to recognition and acceptance. He was often ill as a child and – though he may have wanted to run around and be naughty – he spent most of his time sitting quietly and reading.

The inner specialisation we feel psychologically required to undertake leaves many aspects of who we might be undeveloped. We are in fact stunted, though the world may be very ready to reward the limited, constrained guise we have adopted.

Marx’s delirious capacity to render everything absurd was nothing like the whole of who he was. Just as Eliot’s refined presentation was only an aspect, brilliantly developed, of who he might have been. In friendship Tom and Groucho were looking for balance. They were seeking to reconnect with the parts of their personalities that had been neglected or sacrificed in the pursuit of success.

We can even see the problem in their art – great as it, in both cases, is. Eliot really would be an even greater poet, and a more powerful force in the world today, if he could have more surely inhabited the normal ground of unrefined, unerudite experience: Marx’s home territory. His specialisation in obscure references weakened rather than strengthened his poetic talent. And Groucho has less to say to us today because pure physical comedy, to which he gave so much of his life, grows stale; while his evident capacity for the witty skewering of difficult truths (‘I don’t want to belong to any club that would accept me as one of its members‘) was occasional and scattered.

We’re not great poets or hugely successful comic actors but in our own way we may suffer the same kind of trouble: we too lack balance in our lives. We’re hard working at the expense of enjoying life; we’re hedonistic to the detriment of our careers and relationships; we’re hyper-responsible (which ends up annoying lots of people) or not responsible enough (with the same result). We’re not to be blamed. We don’t have to punish ourselves more for our internal biases, though we might long to find an exit from them.

It’s not weird, therefore, that there can be a draw in friendship to those who, ostensibly, are so different from us; we see in them, if only in the dimmest outline, the needed correction to our own one-sidedness. The slightly brutal irony is that society tends to be suspicious of such friendships: its vision is that like should comport with like. The person in their seventies may hugely value a friendship with someone in their thirties – and vice versa – because each finds in the other a counter-force to their own anxieties. The older person is returned (despite all their fears) to a sense of relevance; the younger is given a much needed longer perspective. But the world doesn’t openly welcome such connections and in no way is set up to foster them.

Or, someone who is quite shy could perhaps find no better friend than another who is very confident socially – someone, that is, to correct their exaggerated anxiety around others. And the devoted socialite might rather urgently need a friend to understand, appreciate and encourage their quieter, more thoughtful side. But standardly we can’t even imagine this happening. It’s one of the tragic misapprehensions of existence: we assume that others are looking for more of the same. There’s a pervasive reluctance to think that poor and rich, left and right, scientist and artist, super-sporty and elegantly languid might – at the level of friendship – crave one another.

If, like T.S Eliot, we were to take the first step and write a fan letter to a very unexpected (but psychologically needed) person, who might it be? Who would it be lovely to be friends with not because they are like us but because they supply what’s missing in us.

We pretty much always know – secretly – the excessive price we’ve paid to survive; we know where our imbalances lie, though self respect may make us reluctant to own up to them. But what specifically is suppressed? What’s missing? Typically it is the opposite of what we’re good at. This isn’t an attack on our merits but a reminder of the excess cost we paid in acquiring our specialised excellence. We’re finely diplomatic, because we’ve slightly run away from being (at times when it’s needed) more directly confrontational. We’re so ambitious because we’re hiding our longing to be cherished for our own sake. The different other comes in as the friend of the abandoned parts of who we are.

Groucho and Tom were sketching the outline of a better world, achieved through a better psychological balance in ourselves. As it happens, they didn’t entirely pull it off. In the end they slightly irritated each other. But the value of their example doesn’t lie in them getting it perfectly right. They are showing us what we long for.

The need friendship meets: to discover in another the missing parts of ourselves