Leisure • Art/Architecture

Henri Matisse

The cultural elite gets nervous about cheerful or sweet art. They worry that pretty, happy works of art are in denial about how bad the state of the world is and how much suffering there is in almost every life.

Seated Woman, Back Turned to the Open Window, 1922

Look at this picture of sailing boats shooting about in the Med, beyond the palm trees, while a chinzy looking woman sits on a sofa. Has the artist forgotten that the world is filled with inequality, corruption and war? The fear is that we might be so absorbed in having a nice time that we forget about the bad things – and therefore won’t trouble ourselves to do anything about them.

However, these worries are generally misplaced. Far from taking too rosy and sentimental a view, most of the time, we suffer from excessive gloom. We are only too aware of the problems and injustices of the world. Our problem is actually that we feel debilitatingly small and weak in the face of them. It’s because we feel overwhelmed and hopeless that we recoil into ourselves.

Cheerfulness is an achievement and hope is something to celebrate. If optimism is important, it is because many outcomes are determined by how much of it we bring to the task. It is an important ingredient of success. This flies in the face of an elite view that skill is the primary requirement of a good life. Yet in many cases, the difference between success and failure can be determined by nothing more than one’s sense of what is possible and the energy one can muster to convince others of one’s due. One can be doomed not by a lack of talent, but by an absence of hope.

Rarely are today’s problems created by people taking too sunny a view of things; it is because the troubles of the world are so continually brought to our attention that we stand in need of tools which can preserve our more hopeful dispositions.

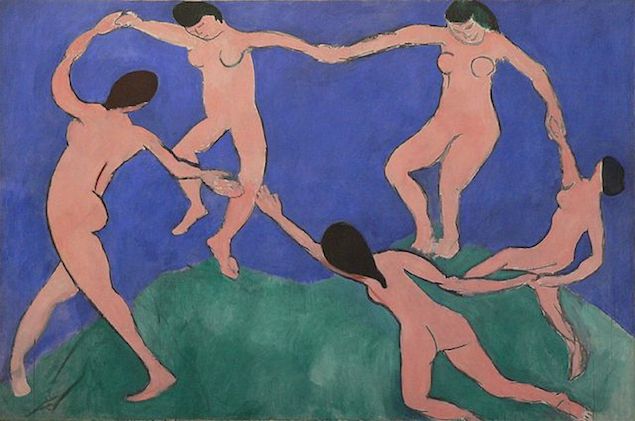

What hope might look like. Dance (I), 1909

The dancers in Matisse’s Dance are not in denial of the troubles of this planet. But from within a normally imperfect and conflicted relationship with reality, one can look at their attitudes as an encouragement; they put one in touch with a blithe, carefree part of oneself which can help one in coping with the inevitable rejections and humiliations. The picture should not be seen as suggesting that all is well: and that, despite the evidence of experience, women always take delight in each other’s existence and bond together in mutually supportive networks.

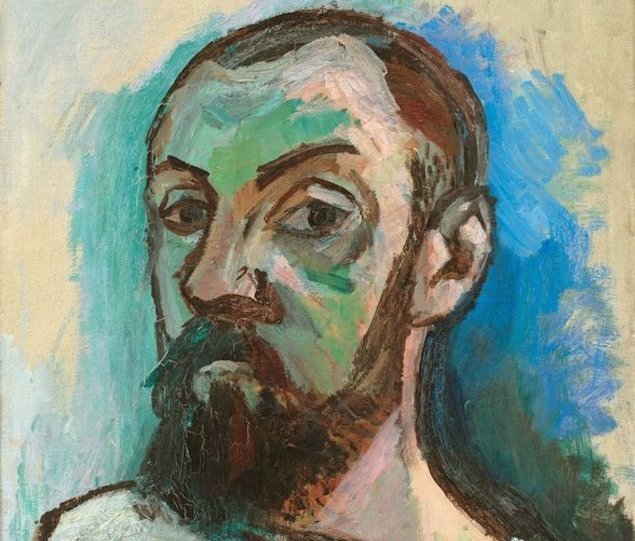

Matisse himself knew a huge amount about suffering (which builds our confidence in his pleasing, hopeful, charming work) – as a glance at one of his self-portraits shows.

Self-Portrait in a Striped T-shirt, 1906

Matisse knew all about tragedy but his acquaintance with it made him all the more alive to its opposites. As he saw it, the real problem was that darkness and misery are so likely to overpower us that we actually need to make a deliberate effort to remind ourselves of cheerful and hopeful things.

Matisse was born in 1869 into a relatively prosperous family. His father was a hardware and grain merchant. He wasn’t supposed to be an artist. His father was very keen that he should have a safe, respectable – and lucrative – career as a lawyer. In his twenties he became desperate to give up his day job in the law office but his father was strongly opposed. Eventually he relented and agreed that Matisse could study – but only so long as he kept to the most traditional and conservative style.

Still Life with Books, 1890. (Message from his father: you keep on painting like this and I’ll keep paying your allowance)

In order to develop as a painter of joyful, bright and sensuous pictures, Matisse had to face down his father, embrace poverty (when all family support was cut off) and be reviled by his teachers and mentors.

In the years before the outbreak of the First World War Matisse started to build up a successful career. He was selling a few pictures. He was getting well known in adventurous artistic circles. Just as he seemed to be making it, the whole world started to fall apart.

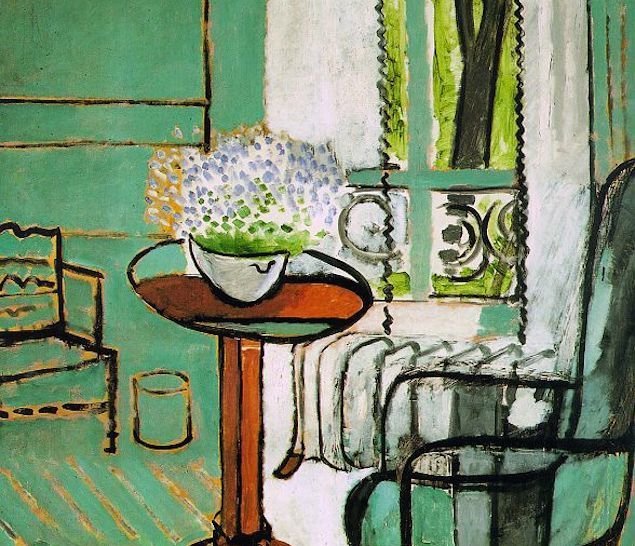

In the year of the Battle of the Somme, he painted The Window.

The Window (Interior with Forget-Me-Nots), 1916

It’s not that Matisse didn’t care about the trenches, a day’s journey from Paris. It intensified his sense of the loveliness of the trunk of a tree just glimpsed through the gap in the curtains, or his delight in the pattern of the floorboards – and the overall freshness and charm of a bowl of flowers in an elegant, but unpretentious room in the city. It’s as if he is reminding himself (and us) that these things are still here. They haven’t been destroyed. It’s not the work of someone who is indifferent. It is created in recognition of how easily one could be paralysed with despair. And the hint of light green leaves through the window might speak kindly to us, even today, when we’re overburdened with our own sense of the weight of life.

Later, there were more private traumas. Matisse was diagnosed with duodenal cancer. He was involved in a protracted and very painful legal dispute with his estranged wife.

Woman in Blue or the Large Blue Robe and Mimosas, 1937

In 1942 when Paris had fallen, and the German 6th Army was pushing through Russia towards the southern oilfields, Matisse painted a number of pictures of dancers, with fabulous legs, reclining in big, soft armchairs.

Dancer and Rocaille Armchair on a Black Background, 1942

The most poignant of his cheerful, hopeful works were produced at the very end of his life, around about 1950 when he was in his eighties. He had been an invalid for years; mostly bedridden, occasionally able to get around in a wheelchair. He knew he was facing death.

The Tree of Life, 1948-51

The deep blue and yellow – and the simple pattern – of the stained glass seems to glow with delight in existence. But Matisse wasn’t expressing a cheerfulness he had recently experienced. The vulnerable, suffering great painter was attempting to ward off his own fears of gloom and despondency; he was reminding us through his genius that there is nothing quite as serious as knowing how to hope.