Leisure • Western Philosophy

Aristotle

Aristotle was born around 384 BC in the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia where his father was the royal doctor. He grew up to be arguably the most influential philosopher ever, with modest nicknames like ‘the master’, and simply ‘the philosopher’. One of his big jobs was tutoring Alexander the Great, who soon after went out and conquered the known world.

Aristotle studied in Athens, worked with Plato for several years and then branched out on his own. He founded a research and teaching centre called The Lyceum: French secondary schools, lycées, are named in honour of this venture. He liked to walk about while teaching and discussing ideas. His followers were named Peripatetics, the wanderers. His many books are actually lecture notes.

Aristotle was fascinated by how things really work. How does an embryo chick develop in an egg? How do squid reproduce? Why does a plant grow well in one place, and hardly at all in another? And, most importantly, what makes a human life and a whole society go well? For Aristotle, philosophy was about practical wisdom. Here are four big philosophical questions he answered:

1. What makes people happy?

In the Nicomachean Ethics – the book got its name because it was edited by his son, Nicomachus – Aristotle set himself the task of identifying the factors that lead people to have a good life, or not. He suggested that good and successful people all possess distinct virtues, and proposed that we should get better at identifying what these are so that we can nurture them in ourselves and honour them in others.

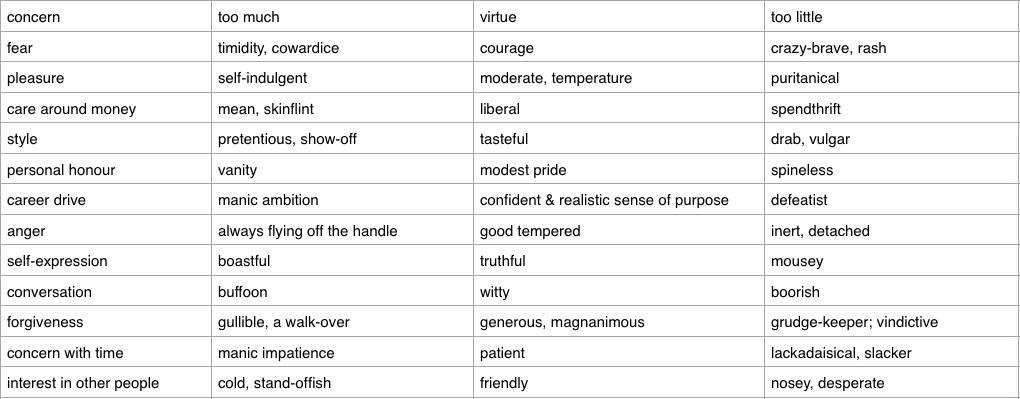

Aristotle also observed that every virtue seems to be bang in the middle of two vices. It occupies what he termed ‘the golden mean’ between two extremes of character. For example, in book four of his Ethics, under the charming title of conversational virtues and vices – wit, buffoonery and boorishness – Aristotle looks at ways that people are better or worse at talking to one another.

Knowing how to have a good conversation is one of the key ingredients of the good life, Aristotle recognised. Some people go wrong because they lack a subtle sense of humour: that’s the bore, ‘someone useless for any kind of social intercourse because he contributes nothing and takes offence at everything’. But others carry humour to excess: ‘the buffoon cannot resist a joke, sparing neither himself nor anybody else, provided that he can raise a laugh and saying things that a man of taste would never dream of saying’. So the virtuous person is in the golden mean in this area: witty but tactful.

In a fascinating survey of personality and behaviour Aristotle analyses ‘too little’, ‘too much’ and ‘just right’ around a whole host of virtues. We can’t change our behaviour in any of these areas just at the drop of a hat. But change is possible, eventually. Moral goodness, says Aristotle, is the result of habit. It takes time, practice, encouragement. So Aristotle thinks, people that lack virtue should be understood as unfortunate, rather than wicked. What they need isn’t scolding or being thrown into prison, but better teachers and more guidance.

2. What is art for?

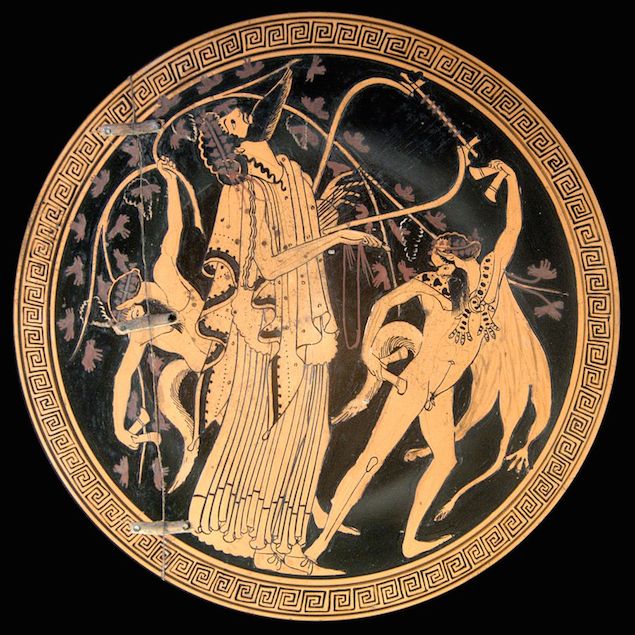

The blockbuster art at the time was tragedy. Athenians watched gory plays at community festivals held at huge open-air theatres. Aeschylus, Euripides and Sophocles were household names. Aristotle wrote a how-to-write-great-plays manual, The Poetics. It’s packed with great tips: for example, make sure to use peripeteia, a change in fortune when, for the hero, things go from great to awful. And anagnorisis, the moment of dramatic revelation when suddenly the hero realises their life is going very wrong – and is, in fact, a catastrophe.

But what is tragedy actually for? What is the point of a whole community coming together to watch horrible things happening to lead characters? Like Oedipus, in the play by Sophocles, who by accident kills his father, gets married to his mother, finds out he’s done these things and gouges out his eyes in remorse and despair. Aristotle’s answer is: catharsis. Catharsis is a kind of cleaning: you get rid of bad stuff. In this case, cleaning up our emotions, specifically, our confusions around the feelings of fear and pity.

We’ve got natural problems here: we’re hard-hearted, we don’t give pity where it’s deserved, and we’re prone to either exaggerated fears or not getting frightened enough. Tragedy reminds us that terrible things can befall decent people, including ourselves. A small flaw can lead to a whole life unravelling. So we should have more compassion or pity for those whose actions go disastrously wrong. We need to be collectively retaught these crucial truths on a regular basis. The task of art, as Aristotle saw it, is to make profound truths about life stick in our minds.

3. What are friends for?

In books eight and nine of the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle identifies three different kinds of friendship: there’s friendship that comes about when each person is seeking fun, their chief interest is in their own pleasure and the opportunity of the moment, which the other person provides. Then there are friendships that are really strategic acquaintances. They take pleasure in each other’s company only insofar as they have hopes of advantage of it.

Then, there’s the true friend. Not someone who’s just like you, but someone who isn’t you, but about whom you care as much as you care about yourself. The sorrows of a true friend are your sorrows. Their joys are yours. It makes you more vulnerable, should anything befall this person. But it’s hugely strengthening too. You’re relieved from too small orbit of your own thoughts and worries. You expand into the life of another, together you become larger, cleverer, more resilient, more fair-minded. You share virtues and cancel out each other’s defects. Friendship teaches us what we ought to be: it is, quite literally, the best part of life.

4. How can ideas cut through in a busy world?

Like a lot of people, Aristotle was struck by the fact that the best argument doesn’t always win the debate or gain popular traction. He wanted to know why this happens and what we can do about it. He had lots of opportunity for observations. In Athens, many decisions were made in public meetings, often in the agora, the town square. Orators would vie with one another to sway popular opinion.

Aristotle plotted the ways audiences and individuals are influenced by many factors but don’t strictly engage with logic or the facts of the case. It’s maddening and many serious people can’t stand it. They avoid the market place and populace debate. Aristotle was more ambitious. He invented what we still call rhetoric, the art of getting people to agree with you. We wanted thoughtful, serious and well-intentioned people to learn how to be persuasive, to reach those who don’t agree already.

He makes some timeless points: you have to soothe people’s fears, you have to see the emotional side of the issue – Is someone’s pride on the line? Are they feeling embarrassed? – and edge around it accordingly. You have to make it funny because attention spans are short, and you might have to use illustrations and examples to make your point come alive.

We’re keen students of Aristotle. Today, philosophy doesn’t sound like the most practical activity, maybe that’s because we’ve not paid enough attention recently to Aristotle.