Leisure • Western Philosophy

Nietzsche

The challenge begins with how to pronounce his name. The first bit should sound like ‘Knee’, the second like ‘cher’: Knee – cher.

Friedrich Nietzsche was born in 1844 in a quiet village in the eastern part of Germany, where – for generations – his forefathers had been pastors. He did exceptionally well at school and university; and so excelled at ancient Greek (a very prestigious subject, at the time) that he was made a professor at the University of Basel when still only in his mid-twenties.

But his official career didn’t work out. He got fed up with his fellow academics, gave up his job and moved to Switzerland and Italy where he lived modestly and often alone. He was rejected by a succession of women, causing him much grief (‘My lack of confidence is immense’). He didn’t get on with his family (‘I don’t like my mother and it’s painful even for me to hear my sister’s voice’) and in response to his isolation, grew a huge moustache and took long country walks every day. For many years, his books hardly sold at all. When he was forty-four, his mental health broke down entirely. He never recovered and died eleven years later.

Nietzsche believed that the central task of philosophy was to teach us how to ‘become who we are’, in other words, how to discover and be loyal to our highest potential.

To this end, he developed four helpful lines of thought:

1. Own up to envy

Envy is – Nietzsche recognised – a big part of life. Yet we’re generally taught to be feel ashamed of of our envious feelings. They seem an indication of evil. So we hide them from ourselves and others, so much so that there are people who will sometimes say, with all sincerity, that they don’t envy anyone.

This is logically impossible, insisted Nietzsche, especially if we live in the modern world (which he defined as any time after the French Revolution). Mass democracy and the end of the old feudal-aristocratic age had, in Nietzsche’s eyes, created a perfect breeding ground for envious feelings, because everyone was now encouraged to feel that they were equal to everyone else. In feudal times, it would never have occurred to the serf to feel envious of the prince. But now everyone compared themselves to everyone else and was exposed to a volatile mixture of ambition and inadequacy as a result.

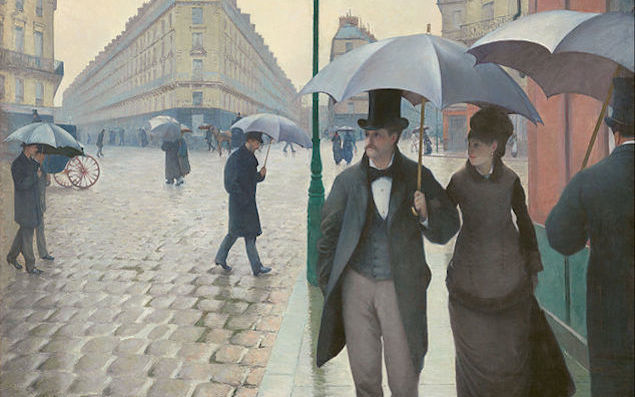

Gustave Caillebotte, Paris Street; Rainy Day, 1877

However, there is nothing wrong with envy, maintained the philosopher. What matters is how we handle it. Greatness comes from being able to learn from our envious crises. Nietzsche thought of envy as a confused but important signal from our deeper selves about what we really want. Everything that makes us envious is a fragment of our true potential, which we disown at our peril. We should learn to study our envy forensically, keeping a diary of envious moments, and then sift through episodes to discern the shape of a future, better self.

The envy we don’t own up to will otherwise end up emitting what Nietzsche called ‘sulfurous odours.’ Bitterness is envy that doesn’t understand itself. It is not that Nietzsche believed we always end up getting what we want (his own life had taught him this well enough). He simply insisted that we must become conscious of our true potential, put up a heroic fight to honour it, and only then mourn failure with solemn frankness and dignified honesty.

2. Don’t be a Christian

Nietzsche had some extreme things to say about Christianity: ‘I call Christianity the one great curse, the one intrinsic depravity… In the entire New Testament, there is only person worth respecting: Pilate, the Roman governor.’

This was knockabout stuff, but his true target was more subtle and more interesting: he resented Christianity for protecting people from their envy.

Carl Bloch, The Sermon on the Mount, 1877

Christianity had in Nietzsche’s account emerged in the late Roman Empire in the minds of timid slaves, who had lacked the stomach to get hold of what they really wanted (or admit they had failed), and so had clung to a philosophy that made a virtue of their cowardice. Christians had wished to enjoy the real ingredients of fulfilment (a position in the world, sex, intellectual mastery, creativity) but had been too inept to get them. They had therefore fashioned a hypocritical creed denouncing what they wanted but were too weak to fight for – while praising what they did not want but happened to have. So, in the Christian value system, sexlessness turned into ‘purity’, weakness became “goodness,” submission to people one hated “obedience” and, in Nietzsche’s phrase, “not-being-able-to-take-revenge” turned into “forgiveness.”

Christianity amounted to a giant justification for passivity and a mechanism for draining life of its potential.

3. Never drink alcohol

Nietzsche himself drank only water – and as a special treat, milk. And he thought we should do likewise. He wasn’t making a small, eccentric dietary point. The idea went to the heart of his philosophy, as contained in his declaration: ‘There have been two great narcotics in European civilisation: Christianity and alcohol.’

Eduoard Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882

He hated alcohol for the very same reasons that he scorned Christianity: because both numb pain, and both reassure us that things are just fine as they are, sapping us of the will to change our lives for the better. A few drinks usher in a transient feeling of satisfaction that can get fatally in the way of taking the steps necessary to improve our lives. It’s not that Nietzsche admired suffering for its own sake. But he recognised the unfortunate – but crucial – truth that growth and accomplishment have irrevocably painful aspects: “What if pleasure and displeasure were so tied together that whoever wanted to have as much as possible of one must also have as much as possible of the other. You have a choice in life: either as little displeasure as possible, painlessness in brief or as much displeasure as possible as the price for an abundance of subtle pleasures and joys.”

Nietzsche’s thought recalibrates the meaning of suffering. If we are finding things difficult, it is not necessarily a sign of failure, it may just be evidence of the nobility and arduousness of the tasks we’ve undertaken.

4. “God is Dead”

Nietzsche’s dramatic assertion about the demise of God is not, as it’s often taken to be, some kind of a celebratory statement. Despite his reservations about Christianity, Nietzsche did not think that the end of belief was anything to celebrate.

Religious beliefs were false, he knew; but he observed that they were in some areas very beneficial to the sound functioning of society. Giving up on religion would mean that humans would be left to find new ways of supplying themselves with guidance, consolation, ethical ideas and spiritual ambition. This would be tricky, he predicted.

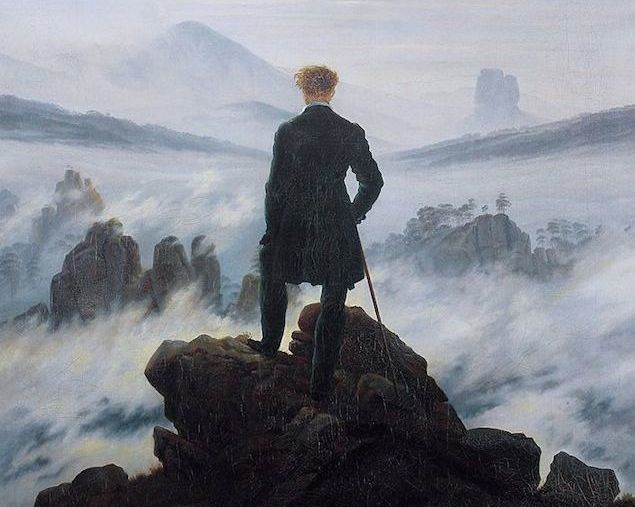

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1818

Nietzsche proposed that the gap left by religion should ideally be filled with Culture (philosophy, art, music, literature): Culture should replace Scripture.

However, Nietzsche was deeply suspicious of the way his own era handled culture. He believed the universities were killing the humanities, turning them into dry academic exercises, rather than using them for what they were always meant to be: guides to life. He particularly admired the way the Greeks had used tragedy in a practical, therapeutic way, as an occasion for catharsis and moral education – and wished his own age to be comparably ambitious.

He accused university and museum-based culture of retreating from the life-guiding, morality-giving potential of culture, at precisely the time when the Death of God had made these aspects ever more necessary.

Edvard Munch, Friedrich Nietzsche, 1906

He called for a reformation, in which people – newly conscious of the crisis brought on by the end of faith – would fill the gaps created by the disappearance of religion with the wisdom and healing beauty of Culture.

Conclusion

Every era faces particular psychological challenges, thought Nietzsche, and it is the task of the philosopher to identify, and help solve, these.

For Nietzsche, the 19th century was reeling under the impact of two developments: Mass Democracy and Atheism. The first threatened to unleash torrents of undigested envy and venomous resentment; the second to leave humans without guidance or morality.

In relation to both challenges, Nietzsche worked up some fascinating solutions – from which our own times have some highly practical things to learn, as he would dearly have wished.