Leisure • Political Theory

William Morris

The 19th-century designer, poet and entrepreneur William Morris is one of the best guides we have to the modern economy – despite the fact that he died in 1896 (while Queen Victoria was still on the throne), never made a telephone call and would have found the very idea of television utterly baffling.

Morris was the first person to understand two issues which have become decisive for our times. Firstly: the role of pleasure in work. And, secondly: the nature of consumer demand. The preferences of consumers – what we collectively appreciate and covet and are willing to pay for – are crucial drivers of the economy and hence of the kind of society we end up living in. Until we have better collective taste, we will struggle to have a better economy and society. It’s a huge idea.

William Morris was born in 1834 into a well-off family. His father was a financier in the City of London and they lived in a large house near Walthamstow in Essex. His father died young (Morris was only 13) and it turned out he had been involved in a range of highly speculative – and only just legal – ventures. A great deal of the family fortune was lost – although a few secure investments remained which gave young Morris a comfortable (though by no means huge) income for life.

The fact that he was always reasonably well-off did not blunt his empathy for financial hardship. Personally and politically Morris was an instinctively warm and generous man. But it did bring a useful perspective: he was acutely aware that there are some key problems which are not caused by shortage of money and which more money won’t solve. So he could never be persuaded that financial growth in and of itself could be the sure sign of improvement – whether in an individual or a national – life.

When he was 18, Morris went to university. He didn’t do much of the work he was supposed to but he had a wonderful time. Almost the first day he made friends for life with a fellow student called Edward Burne-Jones, who went on to become one of the most successful artists of the era.

After graduating Morris spent some time training as an architect. But at this stage, a conventional career wasn’t his main concern. He saw himself as an artist and a poet. He was simply interested in making things for his own satisfaction and maybe for the enjoyment of a few friends. He was not seeking to sell his paintings or be paid for writing poems. Morris’s friends used to call him ‘Topsy’ – because of his volatile, occasionally fiery, temper.

His favourite model was a young actress with a dramatically beautiful face, Jane Burden. She posed as Iseult in his best picture.

William Morris, La Belle Iseult, 1858

A year later they got married. Morris became obsessed with the project of building and furnishing a family house at Bexleyheath, in south-east London. It was called the Red House and pretty much everything in it – chairs, tables, lamps, wallpaper, wardrobes, candlesticks, glasses – were designed from scratch either by Morris himself or by his close friend and architectural collaborator Philip Webb. Artistic friends painted murals on the walls.

The experience of building and fitting out his house taught Morris his first big lesson about the economy. It would have been simpler (and maybe cheaper) to have ordered everything from a factory outlet. But Morris wasn’t trying to find the quickest or simplest way to set up home. He wanted to find the way that would give him – and everyone involved in the project – maximum satisfaction. And it fired Morris with an enthusiasm for the medieval idea of craft. The worker would develop sensitivity and skill; and enjoy the labour. It wasn’t mechanical or humiliating.

He spotted that craft offers important clues to what we actually want from work. We want to know we’ve done something good with the day. That our efforts have counted towards tangible outcomes that we actually see and feel are worthwhile. And Morris was already noticing that when people really like their work, the issue of exactly how much you get paid becomes less critical. (Though Morris always believed, in addition, that people deserved honourable pay for honest work.) The point is you can absolutely say you are not doing it purely for the money.

Textile printing at Merton Abbey, c.1890

Labour could be dignified. It was a timely insight. This was an era of massive industrialisation; workers were pouring into the new factories – even though the conditions were often horrendous. The status of working with your hands, of making physical things was low. It was then (as now) more prestigious to sit at a desk than to stand at a forge or by a kiln.

The problem, though, was that Morris was not only a craftsman and a labourer at the Red House. He was also the client. Of course – sceptics might point out – he could have a great time because this was basically just pursuing a hobby.

Yet this was precisely what Morris didn’t want to do. He was determined to show that the principles of craft and satisfying work (for the worker) could and should be at the heart of the modern world. And that – he realised – meant making them into a business.

So, in 1861 – still in his mid twenties – Morris started a decorative arts business: Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co.; which they like to call simply ‘the Firm’. His colleagues included Burne-Jones, the brilliant poet, painter and charismatic personality Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the architect Philip Webb.

The Attainment tapestry, Morris and Company, 1890

They set up a factory making wallpaper, chairs, curtains and tables. They were very proud not only of the elegant designs but of the quality of the workmanship that went into all their products. They believed that factories should be attractive places, and they were keen for clients and others to come and take a tour and see for themselves the healthy pleasant environment in which the goods were produced.

The firm soon encountered a very instructive problem. If you make high quality goods and pay your workers a fair and decent wage, then the cost of the product is going to be higher. It will always be possible for competitors to undercut the price and offer inferior goods, produced in less humane ways, for less money.

If you ask a comparatively high price – to ensure the dignity of work and quality of materials and so make something that will last – you really risk losing customers.

The factories and machines of the Industrial Revolution had brought mass production. Prices were lower, but there was a loss of quality and a dependence on routine, deadening labour in depressing circumstances. It can seem as if it is inevitable that the low price must triumph. Surely, the logic of economics dictates that the lower price will necessarily win. Or does it?

Design for Trellis wallpaper, 1862

For Morris the key factor is, therefore, whether customers are willing to pay the just price. If they are, then work can be honourable. If they are not, then work is necessarily going to be – on the whole – degrading and miserable.

So, Morris concluded that the lynchpin of a good economy is the education of the consumer. We collectively need to get clearer about what we really want in our lives and why, and how much certain things are worth to us (and therefore how much we are prepared to pay for them).

An important clue to good consumption, Morris insisted, is that you ‘should have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful’. This is a crucial attitude. It doesn’t involve renunciation, it’s not an invitation to bleak renunciation, he’s not trying to make anyone feel guilty or ashamed.

Rather than reaching for lots of quick fixes and items of fleeting use and charm, Morris wished for people to see their purchases as investments and buy items sparingly. He would have preferred for someone to spend £1000 on an intricate, hand-made dining set that would last for decades and grow to become a family heirloom, than for each generation to buy its own cheap alternative, just to be thrown away when fashions changed. This way, people could take pride in and really enjoy the things they bought. There is some sense of satisfaction and pride in buying something you know will last and which can be handed down to future generations.

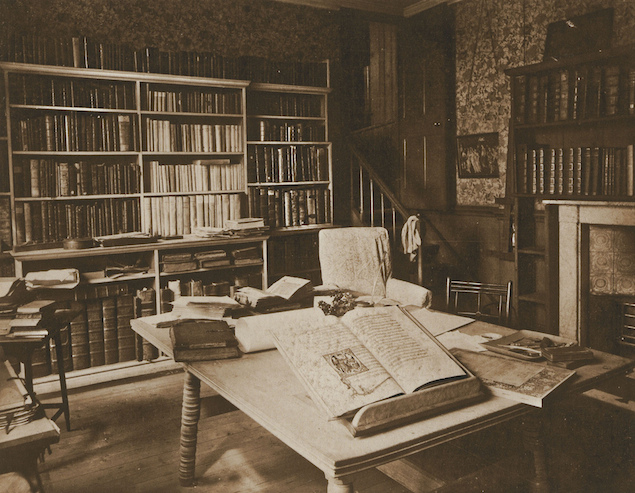

The study at Kelmscott, the home of William Morris, c. 1880

For Morris himself, the business did not work out terribly well. There was healthy demand from the well-to-do. The Morris lines of furniture, wallpaper, fabrics and lamps continued to sell for many years. But he didn’t manage to break into the wider, bigger markets that he aspired to. The point wasn’t to provide more elegance and luxury for the rich. The big idea was to bring solid, well-designed, finely produced articles to the mass consumer. Morris wanted to transform the ordinary – not the elite – experience of buying things.

One of his last creations was a utopian story called News from Nowhere. In it he imagines how, ideally, a society would develop. He learns a lot from Marxism: this is a society with strong social bonds, in which the profit motive is not dominant. But he pays equal attention to the beauty of life: the expansive woodlands, the lovely buildings, the kinds of clothes people wear, the quality of the furniture, the charm of the gardens. Morris’s health declined in his sixties. In the summer of 1896, he took a health cruise to Norway. But the fjords didn’t work and he died of tuberculosis a few weeks after he got home.

Morris directs our attention to a set of centrally important tests that a good economy should pass.

How much do people enjoy working?

Does everyone live within walking distance of woods and meadows?

How healthy is the average diet?

How long are consumer goods expected to last?

Are the cities beautiful (generally, not just in a few privileged parts)?

The economy can (with fatal ease) feel as if it is governed by abstract, complex laws concerning discounted cash flows and money supply. His point is that, nevertheless, the economy is intimately tethered to our preferences and choices. And that these are open to transformation. It may not be necessary (as Marx thought) to bring factories and banks and all the corporations into public ownership; and it may not be necessary (as Milton Friedman and others claimed) to wind back government impact on markets. The true task in creating a good economy, Morris shows us, lies much closer to home.